Alice Könitz's Los Angeles Museum of Art

In 2012, artist Alice Könitz started the Los Angeles Museum of Art, after some friends from her native Germany asked about showing their work in L.A. "I'll build you a museum," Könitz told them. The project seemed as relaxed in ambition as it was in inception. It would have been "perfectly fine," Könitz says, "if LAMOA was a one-show event, or if the museum only ever showed one object." Like much of her work, the initial 9 foot-by-13 foot open-air pavilion on a patch of cement outside her Eagle Rock studio was at once the thing itself, a functioning exhibition space, and a confrontation with possibility: what it means to unburden the life in front of us from the weight of what else it could be. "I take a long time to figure out whether it actually works or not, and then I'm mainly excited about seeing it," Könitz says. "I'm just enthusiastic enough about figuring something out."

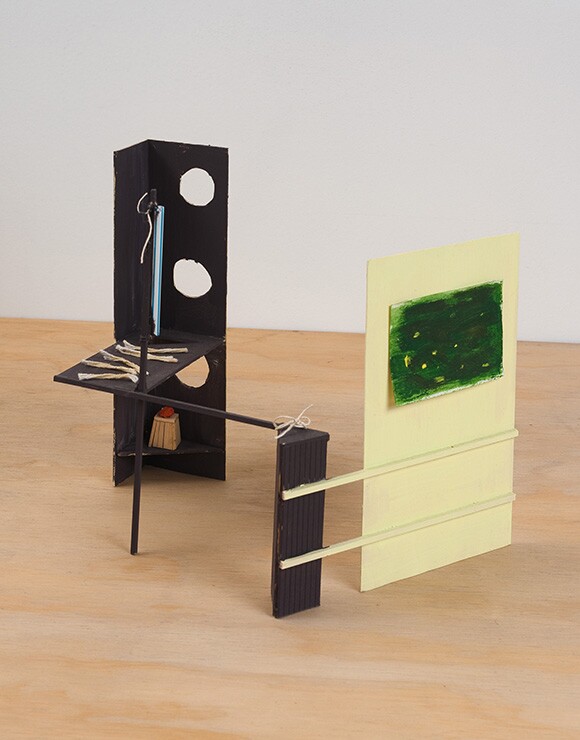

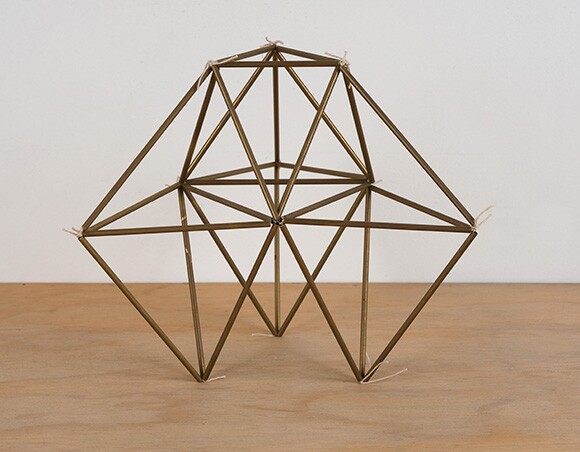

Many of Könitz's sculptural works have a "maquette-like quality," she says. With interlocking geometric forms, they also recall mid-century design and modernist architecture, but instead of steel, concrete or stone -- our usual braces against the wear of elements and time -- Könitz is more likely to work in relatively flimsy materials such as "thin wood I can cut with a mat knife," bamboo skewers and banana peels. The piece "Mall Sculpture," for a solo show at Susanne Vielmetter a few years ago, is made of felt and Chromalux gold foil paper, part of a series she described as "four works that could be read as proposals for public works."

"Of course, it implies metal and has a relation to more sturdy materials" Könitz says. "But the pieces weren't ever supposed to be made out of metal. They were supposed to be out of this beautiful gold paper that is actually more shiny than metal."

She recalls being in an elevator recently, a sleek fancy affair, and noticing that the chrome surface treatment had started to warp and break loose. "It's not unusual to use pretend materials. I'm just more up front about the pretend," Könitz says of her work. That her pieces are placeholders is both the point and besides it. For Könitz, prototypes are things themselves; they are premises not in search of a proof. Other works are even more explicit stand-ins for impermanence, not disposable but not forever. "Usually if you don't own the work, you always have a temporary experience anyways," she says. She has held day-long residencies at LAMOA and made sculptural props for video pieces that negotiate a hierarchy of objects, seeking to "validate forms by use, not by their materials," including rafts to ferry people on the Los Angeles River. "I get pleasure out of making it in the first place, figuring out how it will work. It doesn't have to go anywhere beyond that," she says. "I mean, except for the pyramids and maybe a few other things, they won't last forever either."

In 2008, Könitz was selected for the Whitney Biennial, another simultaneous emergence and valediction, the way every opportunity can seem burdened by its own potential squandering. For the Whitney, Könitz offered a raffle: A trip for one to Los Angeles, to visit to a particular hidden stretch of the Glendale Freeway. "When I first moved here," to attend CalArts, "I came across this empty concrete platform that you really weren't supposed to see if you were, like, a good driver. You look in front of you, you look ahead at where you're driving," she says. "I do stretch my head, that's how I saw this thing." The thing was a ramp to nowhere, a piece of a the never-finished Beverly Hills freeway. Könitz had earlier built a model proposing an elevator to this "forgotten space," that would lift viewers from the traffic to the abandoned site above it. With the raffle, Könitz seemed to be embracing another fiction: that there was victory in actually standing at the abrupt end, something distinct from imagining it.

At LAMOA, exhibitions over the last two years included a piece of breakaway glass that no one broke until the exhibition was over, just installed there, unshattered. The museum has since expanded: For Made in L.A. 2014 at the Hammer Museum, curator Michael Ned Holte, a longtime champion of Könitz's work, invited the artist to create three display systems showing work from LAMOA's collection. (She made maquettes of each display.) One is dedicated to gifts and work by people with whom Könitz had an intimate relationship, including a coin given to her by Carl Andre after she worked as his driver for a week, a kinetic sculpture by her father and a painting by her boyfriend, the artist Peter Kim.

A second section recreates the footprint of the original LAMOA space, displaying pieces by artists whose "work has been present in my mind for a long time." And the third display, a vitrine of metal pipes and plexiglass, holds pieces that are both self-evident sculptures and references without a cause, including a sliced plasticine "Constructivist Bozzetto" -- from Italian for "sketch" -- by Margaret Honda, and a painted wooden concept for a barbecue franchise hut by David Hughes. As Könitz wrote in the stapled and photocopied catalogue accompanying the nesting of the semi-private LAMOA into the semi-public Hammer Museum, Hughes' "BBQ Pavilion" is about, "the complications of moving a smaller structure into a bigger structure, the gaps that necessarily arise, and the way that those structures can support each other."

This month, the LAMOA annex was saved from disassembly when Könitz was awarded the juried 2014 Made in L.A. Mohn Award, along with a $100,000 prize. "Storing it would have cost more than building it," she explains. Könitz lost her studio recently, and the award means not only that the LAMOA collection is, as she puts it, "in the Hammer collection now, I guess." Yet, now she can "move without the museum," she says. If the privilege of living is to be perpetually in-progress, Könitz's work is both our plans and the distance from them, the way we will never really be finished until we're done.

The Los Angeles Museum of Art is on view at Made in L.A. 2014 at the Hammer Museum, 10899 Wilshire Blvd, Los Angeles, through Sept. 7.

Dig this story? Sign up for our newsletter to get unique arts & culture stories and videos from across Southern California in your inbox. Also, follow Artbound on Facebook, Twitter, and Youtube.