The Cuban Exiles of Echo Park

In Partnership with USC Libraries to actively support the discovery, creation, and preservation of knowledge at the University of Southern California and beyond.

For nearly two centuries Cuban émigrés have found a kind of freedom in the United States that was lacking in their beloved island.1 The ties between the Cuban community and Echo Park can be traced back more than five decades when members of the Presbyterian Church of Echo Park met the first flight of Cuban refugees in 1962. Like its more well-known counterpart in Miami, the Los Angeles neighborhood of Echo Park came to be known as "Little Havana" in the 1960s; for many émigrés it was a gathering site to protest Castro's regime and share the challenges they faced in assimilating to American culture. Prominent Cuban exiles such as sculptor Sergio López-Mesa and composer Aurelio de la Vega built distinguished careers in Los Angeles, and their artistic contributions would be memorialized and celebrated in Echo Park and throughout the city.

When Fidel Castro overthrew dictator Fulgencio Batista in 1959, Cuban intellectuals, filled with utopian ideals, returned home hoping to remake their society. For a time, those hopes flourished. Literary magazines emerged such as "Lunes de Revolucion," a socially conscious, independent weekly that featured such contributors as Jean Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir. The efforts of intellectuals and artists were quickly squashed, however, when Castro's revolutionary stance morphed into a dictatorship. Under Castro's rule, creative endeavors that didn't conform to his rigid definition of art were deemed counter-revolutionary.2 The decisions of the Castro government during its first six months in power set in motion an initial wave of emigration, the members of which would be named the "Golden Exiles." When the government confiscated the property of the Cuban elite, many of whom had worked for the Batista government or American-owned businesses on the island, most fled the island for Florida, in fear they would be arrested as enemies of the state.3 In response to the massive influx of Cuban refugees to the Miami region, U.S. authorities instituted a voluntary resettlement program. For those interested, job interviews were set up and free out-of-state transportation was provided. Between 1961 and 1966 over 14,000 exiled Cubans moved to California.4

With no uniting hub like Miami's Little Havana or New Jersey's Union City, Cuban exiles in Los Angeles relied on their tight-knit network and entrepreneurial spirit to form political and social clubs, which met in restaurants, bakeries, and private homes. The first wave of Cubans arrived in Los Angeles in the 1960s and settled in Echo Park. Within a few years, Cuban-owned business began to open along Sunset Boulevard, including El Carmelo restaurant, La Economica shop, the newspaper 20 de Mayo, and the jewelry store Alamar. As the community gained economic strength, exiles dispersed to Glendale, Downey, South Gate, and Huntington Park. Today, about 80,000 Cuban-Americans live in the Los Angeles area, and another 40,000 live in outlying areas.5

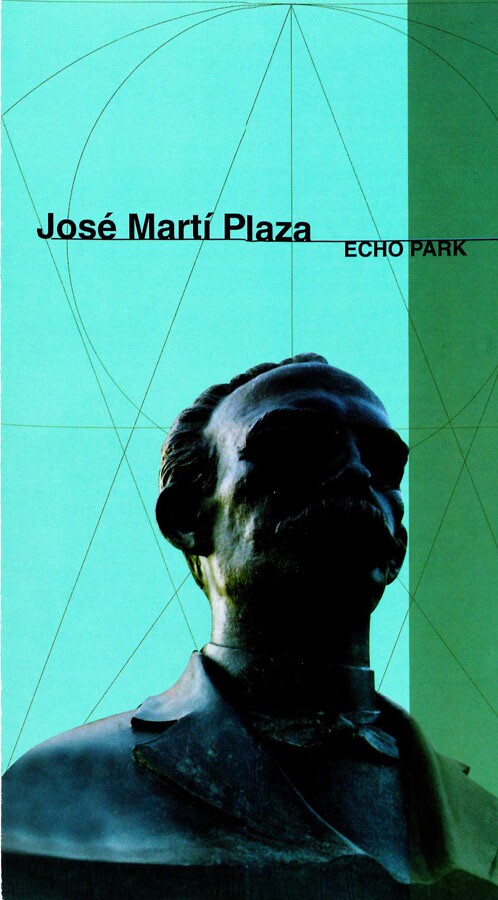

For more than 20 years, Los Angeles -- and Echo Park in particular -- has served as a rallying center and cultural hub for Cuban transplants. The surrounding neighborhood and adjacent park became the site for impassioned anti-Castro demonstrations. In 1976, to highlight the influence of the Cuban community, the city designated the intersection of Park Avenue and Echo Park Avenue "José Martí Square," and sculptor Sergio López-Mesa received a commission to create a bust of José Martí, the beloved Cuban writer and champion of Latin American identity. (One of Martí's poems inspired the lyrics for "Guantanamera," now a definitive protest song emblematic of Cuba.)6

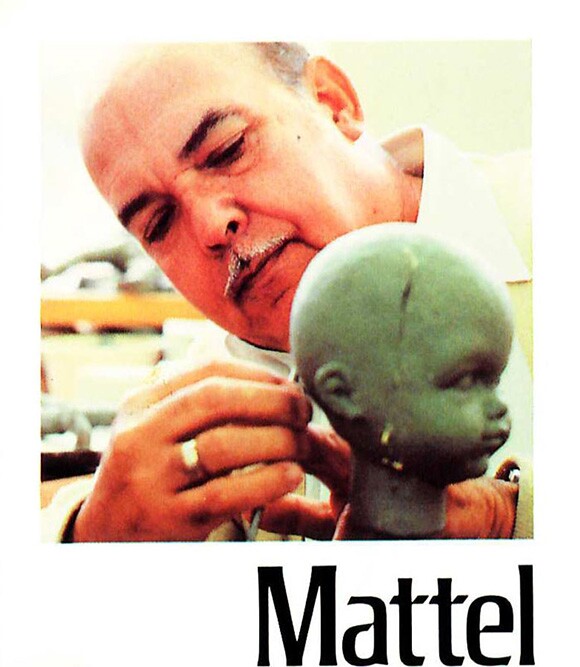

López-Mesa thrived under Batista's regime. As a young artist, he received support from the Cuban Department of Culture, which allowed him to hone his craft in Rome. Upon returning to Cuba from Italy he served as the Director of the Departamento de Bellas Artes and as a professor at the Academia de San Alejandro. He received commissions for numerous projects and his work was prominently displayed throughout the country. However, by 1961 López-Mesa found his work and allegiances branded anti-revolutionary. Like many other artists and intellectuals he faced the difficult choice of adhering to the aesthetic mandates of the new regime or accepting dire consequences. He chose to flee his homeland and made his way to Miami. Despite the strain of living in exile, he continued to work as a sculptor, eventually becoming chair of the art department at the University of South Virginia. López-Mesa would never return to Cuba, and unfortunately many of his public sculptures there were destroyed -- all but erasing his legacy from the island. In 1973, he moved to Los Angeles, where he continued his sculptural work, even creating the first Latina Barbie doll for Mattel.

López-Mesa's most notable and widely recognized work, his bronze bust of José Martí, remains a memorial to Echo Park's role as a gathering place for Cuban exiles. Over the years, the neighborhood's makeup has considerably changed. Today, a mixed population calls Echo Park home, and the majority of Cubans exiles have settled in outlying neighborhoods.

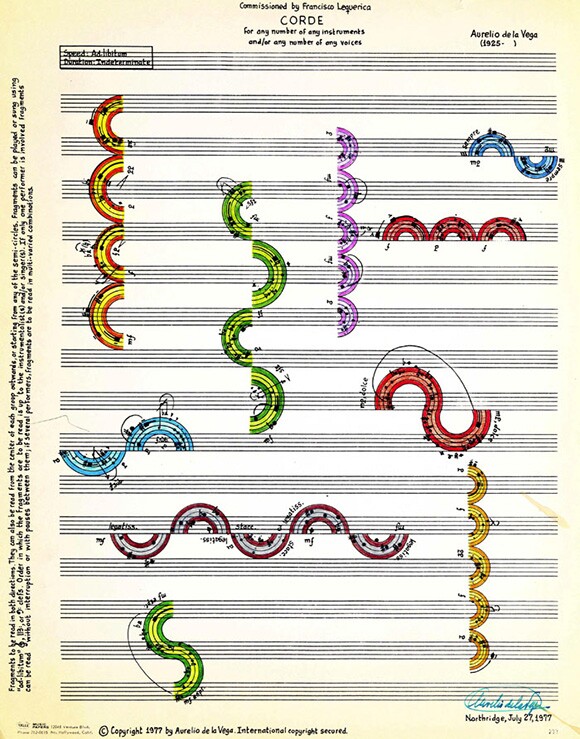

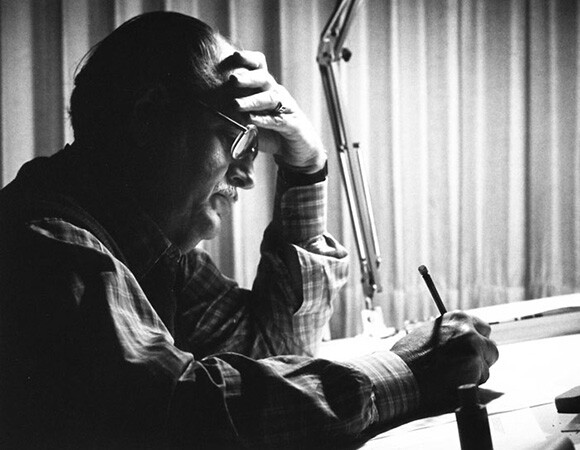

The subject of one of Sergio López-Mesa's sculptural studies, Aurelio de la Vega, is a musician, composer, and fellow Cuban exile living in Los Angeles. Like López-Mesa, de la Vega felt constrained as an artist living under Castro's regime. An internationally acclaimed musician and composer, de la Vega secured a position as a cultural attaché of the Cuban Consulate in Los Angeles, where he studied with Ernst Toch and German exile Arnold Schoenberg. Prior to his visit de la Vega was dean of the school of music at the Universidad de Oriente, music advisor to the National Institute of Culture, and vice president of the Havana Philharmonic Orchestra. De la Vega's father was an executive for the national electric company, and lost his position after the revolution. After the Cuban government confiscated the family's property and questioned their allegiance, they fled for safety to America. Reflecting on his exile experience, de la Vega surmised that he probably would have come to Los Angles anyway, due to his interest in music technology. Under Castro's totalitarianist regime, musicians and the work they produced were supposed to be symbolic expressions of the Communist movement. De la Vega rejected the practice, believing the nationalistic standard of performance and composition camouflaged a musician's deficiencies and only produced mediocre work. As an artist de la Vega always felt like an anti-nationalist. He says music must be so distinctive, and so important that people will recognize the contribution to the country, not vice versa. He returned to Cuba in 1959 to see his family but preemptively secured a U.S. work visa by accepting a position as the director of the electronic music studio at California State University Northridge.

Today, the 88-year-old de la Vega no longer has connections in Cuba. Under Castro's regime, many of his friends were killed while others remain in prison. Living in Los Angeles had a tremendous impact on his music. In the 1960s, there was a surge of interest in electronic music. Despite the loss of his homeland, he felt liberated creatively and the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s brought more complexity to his musical works. De la Vega describes his creative evolution as a blend of technical and aesthetic duality, which is evident in his beautifully crafted musical compositions "Corde" (1977) and "Astralis" (1977). De la Vega was an active member of the Los Angeles expatriate community and participated in Echo Park's annual Cuban Music Festival. Reflecting on his life as a Cuban exile de la Vega describes the emotional strain exiles experience saying, "When you leave your home, and you have done nothing wrong, you experience a pressing, a depression."

Los Angeles played a seminal role in providing refuge for many Cubans who sought to rebuild their lives and who were still making sense of the political upheaval. Unlike other exiles who made their way to Los Angeles, Cuban exiles received government assistance to move west. Los Angeles' Cuban entrepreneurs, businesses, and artists enriched the history and complexity of the city. Echo Park's exile community laid claim to the neighborhood, transforming its eponymous park into a site for annual celebrations and political protests. Sculptor Sergio López-Mesa memorialized the essence of Cuban heritage through his bust of José Martí. Echo Park may no longer be "Little Havana," but the sculptor's tribute to the poet and revolutionary remains a constant, invoking the passion and struggles that so many exiles experience as they attempt to retain their culture and embrace newfound liberties. As Aurelio de la Vega eloquently states, "in many ways being Cuban is a conceptual nationality, not feeling at home anywhere and feeling at home everywhere" -- a sentiment that resonates with all exiles seeking solace in an adopted homeland.

Notes:

1 Alex Anton and Roger E. Hernandez, "Cubans in America" (New York: Kensington Books, 2002), 4.

2 Christopher Minster, "Biography of José Martí" accessed November 20, 2013 http://latinamericanhistory.about.com/od/historyofthecaribbean/p/josemarti.htm

3 Alex Anton and Roger E. Hernandez, "Cubans in America" (New York: Kensington Books, 2002), 53.

4 John F. Thomas, "Cuban Refugees in the United States," The International Migration Review, (Spring 1967), vol. 1, no. 2: 52.

5 Maria Elena Fernandez, "L.A. at Large; Cuban Cafecitos and All the Comforts of Home," Los Angeles Times, February 6, 2001.

6 Dorothy Townsend and Jerry Belcher, "Last Stop on Way to New Life Cuban Refugees Arrive Here," Los Angeles Times, May 10, 1980.

Dig this story? Sign up for our newsletter to get unique arts & culture stories and videos from across Southern California in your inbox. Also, follow Artbound on Facebook and Twitter.