Can Creative Practice Gentrify Creative Practice?

OP-Art: Opinions and editorials about art, institutions, and the relationship between them.

"Dull, inert cities, it is true, do contain the seeds of their own destruction and little else. But lively, diverse, intense cities contain the seeds of their own regeneration, with energy enough to carry over for problems and needs outside themselves."

- Jane Jacobs, "The Death and Life of Great American Cities"

In these past five years, considered as the recovery from our Great Recession of 2009, Los Angeles' communities of artists and urbanists have experienced qualitative changes among the infrastructures that support there activities. These changes can be seen in the growth of bicycle lanes and culture, the development of the sharing economy, the expansion of commercial gallery spaces, and the inclusion of socially held artworks within major museum exhibitions. Where some may use positive terms for these changes, others may use more loaded words like gentrification, economization, commodification, and bureaucratization. And while these phenomenon have different routes, the citizens who invest meaning into them sense the effect. It is for this reason that I choose to catch up with people who've taken part in the artistic, cycling, and sharing communities of Los Angeles; to discover how they feel the success of their projects.

The Echo Park Time Bank was co-founded by L.A. Resident Automn Rooney in March 2008 at the dawn of the economic collapse. "We started with 20 friends in my living room not knowing that six years later it would be 1200 members across thirteen L.A. neighborhoods trading 8,000 hours per year," she says. Time banking allows members to trade units of time of labor with one-another for work they need done, rather then cash. "We never really did outreach, approx 10-30 people apply per month based primarily on word of mouth. Our non-profit is now called Arroyo S.E.C.O. In addition to the Time Bank we manage a learning network for Time Banks across California called the CA Federation of Time Banks." They recently launched the Community Revolving Loan Fund and Local Economy Incubator as a way to support small business and cooperatives.

"I see the economic melt down as a great opportunity," Rooney reflects. "We can't go on in this unsustainable way forever. This Time Bank experiment makes me feel secure because I know that my community can thrive even in dire circumstances. We are resilient and have found a way to adapt to the crisis by supporting each other. It has improved my quality of life and sense of well-being. Hopefully it has for others as well. The economic recovery will not happen by trying to repair the existing system. We need to look at alternatives and there are plenty of good ones available. I'm optimistic."

For Automn Rooney, the continued development of Los Angeles sharing economy has meant the growth of her subtly non-profit, creating an economy of surplus time, pleasure, and community. The flip side to Rooney's notion of the sharing economy is the growth of profit-driven sharing services like Lyft, Uber, and Airbnb. These are services that facilitate the commoditization of an individuals surplus capital; an unused a bed, an idle car. Recently taxi drivers held a protest rally in Downtown Los Angeles demanding reforms to this new sector of the economy; their slogan "Unregulated, Unsafe, Unacceptable."

And while protests by one entrenched sector of the economy feeling its economic interests threatened by a newer younger group is not new, there have been ripples of support from L.A.'s more politically oriented community. After witnessing the rally himself El Chavo, the pen name for lifelong L.A. resident and city blogger, commented online, "I know the cabbies have their jobs at stake but what I find unacceptable is that this sharing economy is turning actual sharing into a shitty Wal-Mart job." Chavo was a co-founder of the late Highland Park (2001-2005) community and anarchist space Flor Y Canto. Flor Y Canto made its mark sharing literature, computer time, and space among their formally working-class and Latino dominated North East L.A. neighborhood.

To the profit-oriented platforms like Uber and Lyft Rooney says she is excited for the sharing economy to become part of popular consciousness, but she believes that ventures aiming to profit off sharing will not survive long term. "Middlemen and hierarchies are old paradigm," she says. "I'm most excited about cooperatives these days. Workers can't be exploited if they own the business. The challenge will be to change the consciousness from competition to collaboration. It's human nature to collaborate but we've had to suppress it for so long. There will be growing pains but it will be worth it." A chore value of her Arroyo S.E.C.O. organization states, "Alone, we are limited in what we can achieve. Networks are stronger than individuals. When we work together, we can build the world we envision."

Another sector of L.A.'s urban infrastructures feeling the pressure of its burgeoning popularity is bicycling. It's an activity that has grown in popularity as a solution to regional transportation issues since the first citywide Ciclavia in 2010, and is an element in Mayor Eric Garcetti's recently-announced Great Streets initiative. When questioned online about the changes experienced in L.A.'s bicycle community in the past several years John Jones of East Side Riders Bike Club stated, "The bike movement in South LA/Watts is on the rise. ESRBC is taking charge in showing our community that cycling is important and can be another sport for our youth. We're also leading the way on advocacy in the south L.A. and southeast communities." Kelly Martin was the first paid employee of the Los Angeles Bicycle Kitchen and today works with the Los Angeles County Bicycle Coalition. She says, "There are a lot of different folks who have activated a lot of great stuff in the last few years: Diversity, equity and cleverness," In spite of this creative work by diverse cycling advocates, Martin has been disappointed by anecdotal references to bicycling as a symbol of unwanted economic gentrification.

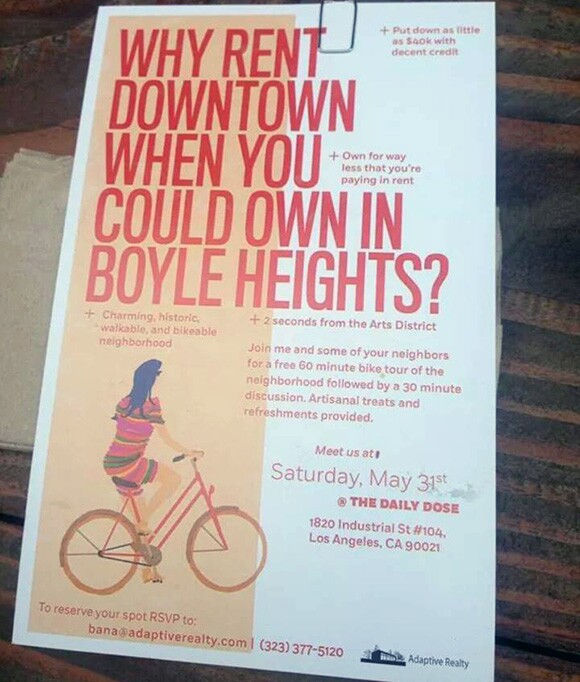

In a recent forum I hosted at the Santa Monica Museum, Martin discussed a well-documented kerfuffle surrounding a flyer distributed by a Boyle Heights developer now known as the "Gentriflyer." The flyer featured a drawing of a girl on a bicycle and encouraged Downtown renters to become homeowners in Boyle Heights. It also advertised a bicycle tour of Boyle Heights for the Downtown renters "Artisanal treats and refreshments provided." At the Santa Monica Museum forum Martin shared a contradictory fact she's occasionally experienced working as a cycling advocate with the city; these days more marginal L.A. communities might be reticent to see bicycle lanes appear on their streets. They see these lanes as a route for encroachment by troops of young professionals carrying upon their two-wheelers the threat of economic dislocation through redevelopment of established communities. The transportation amenities accompanying multi-modal models of urban re-design, sought by creatives, in this instance raises the specter of eviction. This is a now familiar media story and a fact for less affluent neighborhoods. In the case of cycling as in other places, the success of a good thing brings about an unanticipated set of concerns for another group.

Starting in 2008, the three major Los Angeles Museums (MOCA, LACMA, Hammer) began presenting ambitious programs tapping into the community-oriented zeitgeist emerging then in L.A.'s art-oriented sectors. Back then, the money for the museums public engagement programs were tied in part to grants premised on creative place-making and diverse community involvement. (Two of the three institutions initially funded their public engagement art programs through grants from the Irvine Foundation, the other from Met Life.) Ideologically these qualities of participation, diversity, and active engagement, are the positive qualities reflected in New Urbanism and contemporary forms of multi-modal oriented models of urban design. The negative aspect is gentrification, and bureaucracy.

With Machine Project Field Guide To The Los Angeles County Museum Of Art (2008) and Fallen Fruit's EatLACMA (2010), these events at major art institutions began to insert a new form of social-representation into these formally locally held art collaborations. This rupture rearranged the context of what were then seen as quirky and local institutions: Machine Project, an expansive curatorial experiment based in Echo Park; Fallen Fruit, a gleaning manifesto and action group based in Silver Lake. These museum exhibitions opened up a more complicated narrative for socially based projects: narratives of professionalism, and political economy. Before these museum projects these two art projects operated in part by tapping into the broader (perhaps naive or idealistic) art communities gift-economy. After the institutional acceptance of Machine Project and Fallen Fruit within wealthy art institutions, relying upon the benefits of the gift-economy to insure participation by other L.A. based artists was not quite as easy. Of this transitional moment Matias Veigner, a former member of the still operational art collaborative Fallen Fruit, told me, "I have a different relationship to social practice than I had earlier. Certainly it is a more nuanced one."

In 2009, the commercial gallery Blum and Poe opened up for itself an almost museum-sized gallery in Culver City. Previously Blum and Poe had been a modestly sized, yet ambitious, art gallery at the fringes of Santa Monica. With its modern architecture and contemporary blue-chip roster Blum and Poe's new expansion was a declaration of serious capital and purpose. In the intervening years this strategy has been copied by a growing group of commercial galleries in Los Angeles wanting to broadcast a similar relationship to spectacular consumption and contemporary art. Since the economic collapse, oddly enough, the contemporary art market in Los Angeles has emerged as an area of capital investment. With those able to participate in it, and with the development of the transnational art fair economy to support it, the symbolic capital made tangible by the mueseumification of Blum and Poe has been an irresistible statement for other L.A. art galleries.

This is the story for the Night Gallery, which former to its downtown expansion was a louche DIY art gallery in a strip mall in the lowbrow neighborhood of Lincoln Heights. Then its attitude of "come, hang-out together, we're in Lincoln Heights" and "yeah arts on the wall, but the conversations here between us is even better", gave it the reputation as an innovative and edgy gallery to be seen at. In January of 2013 it to opened its own large designer art gallery near Downtown Los Angeles. I emailed an anonymous individual who'd been associated with the gallery about his feelings regarding the change in scale at Night Gallery. They said, "I assume the changes are most typical of any homegrown and heartfelt community organizing turned for-profit endeavor." They added, "Once money, or the potential for money, fame, and power come into the picture a community that was brought together by socializing and making/conversing turns into a string of affiliations based around individual interests. It surely is not like it was before both in terms of participants, clientele, and physical environment to the point where I do not hang out there anymore, and haven't for some time. The magic got lost somewhere before it moved to its new location when true artists turned into a combination of aggressive and aspiring young professionals, and teeny-boppers looking for free beer and weed as well as a scene to grab onto that was publicized as cool." They concluded with, "the usual disappointing ending to what began as an interesting project."

To seek clarity on the issue, I spoke with a younger artist, John Burtle about the effects of these sorts of expansion. Burtle exhibits and sells art with the bi-coastal Michael Benevento gallery and is an active member, amongst many, of the artist run and oriented radio stationKCHUNG. Boisterous and cacophonous KCHUNG has received critical notice in the New York Times. The collective is included in the current and "career making" exhibition "Made In L.A.," now at the Hammer Museum. They are presenting KCHUNG TV, and producing performances for live audiences and web broadcast. I saw one of these live shows the opening weekend of "Made In L.A." at the Hammer, a comedy showcase. It was a one of a kind event with art historical, costumed, and intellectual humor -- it worked really well.

Prompted by the string of successes the station has had in the last year, beloved KCHUNG radio personality and seer Guru Rugu, made an apocalyptically prediction in a March 2 broadcast. He predicted the end was near for KCHUNG. He forecasted a wave of invading and lame New York artists who would fight for airtime for their lame New York artist idea of a radio show. All to make it big herein the artworld. Rugu warned that this piling-on of mediocrity and careerism would lead to the eventual destruction of the station.

Despite Rugu's warning Burtle suggests that with its success KCHUNG has been asking itself about its goals. They can continue to be a volunteer run radio station (as they are today), or with the money that the large collective earns from engagements they imagine being able to hire a paid staff person to administer the station. Burtle describes how this would allow for the opening up of new broadcast time slots. Success in this case would allow KCHUNG to expand its broadcast schedule to even more of the waiting pool of creative DJs, artists, writers, and performers populating Los Angeles.

Burtle suggested to me that the cities community-oriented projects that have expanded into more professional context, they are somewhat burdened with having to focus more on negotiating their image; down to the way they conduct a press releases. He explains" If a group does something in there own basement versus in a large museum, and they announce it in the same manner, physically there's a limit of space there." Burtle suggests that when the radio collective is working with a small and more familiar audience there is less at stake and more tolerance for failure. He explains, "When you are working with a larger institution there's a desire for it to be good". Specifically regarding the opportunity KCHUNG has with the "Made In L.A." exhibit he says "the way we are doing events with the Hammer Museum, we can't have the same limitless what ever you want to do is OK attitude regarding our programming there. So as things become institutionalized things become less flexible. So often, but not always, growth can be less conducive for experimental programming." Burtle went on to explain to me how the Hammer Museum laid out for all the artists things they couldn't do in the museum like have live plants, smoke machines, or open flames. They are not allowed to yell "fire" in the museum. These are things that KCHUNG programmers might have done in other contexts. Burtle says that it was suggested to KCHUNG that if they were to "get naked and have an orgy" it would need to occur on a day when the museum was closed to be broadcast later.

Despite these and other restrictions Burtle says he doesn't want to focus on the limitations and he's "not scared for KCHUNG." Yet he does stress how he is one member of a large opinionated body of artists. Tempting fate Burtle tells me, "Most recent arrivals in L.A. from New York are actually nice." He says the exposure the Hammer exhibit will give the collective "its great." He suggests that values and forms represented by the KCHUNG collective will get out further because of the show. And "some times my mom goes to museums."

Personally speaking, I understand how art is a business, and appreciate the fact that some artists strive to make a living selling objects through galleries, or participating as social practitioners within bureaucratic institutions. These institutions like a city are responsible partners supporting challenging and important work. What I question is how art institutions, pubic or commercial, through their hegemonic power over the creative imagination, may unwittingly foster a flattened measure of success echoed by artists in Los Angeles. A measure that is equated to a standard of professionalism that is regressive, or responsive only to market forces. I do have worries for the diversity, generosity, innovation, and DIY energy characterizing my own experience of my community in Los Angeles.

In 2013 artist Rick Lowe posed a question at the Creative Time Summit in New York City, "Is social practice art gentrifying community arts?" By this he was wondering if contemporary forms of socially engaged art rendering invisible older forms of art making that are not particularly oriented towards addressing, or being represented within, formal art settings. The focus of my article has been somewhat different. Today in Los Angeles where businesses, developers, museums, and city governance are changing the reception and application of community grown initiatives, I've found a similar question worth asking, "Is creative practice gentrifying creative practice?" What is certain to me is that in the last several years here in L.A., things have changed, it could be scale or it might be something else.

Dig this story? Sign up for our newsletter to get unique arts & culture stories and videos from across Southern California in your inbox. Also, follow Artbound on Facebook, Twitter, and Youtube.