The Brockman Gallery and the Village

In collaboration with Nka Journal of Contemporary African Art

Nka focuses on publishing critical work that examines the newly developing field of contemporary African and African Diaspora art within the modernist and postmodernist experience and therefore contributes significantly to the intellectual dialogue on world art and the discourse on internationalism and multiculturalism in the arts. The following piece was originally published in Nka's Sping 2012 issue.

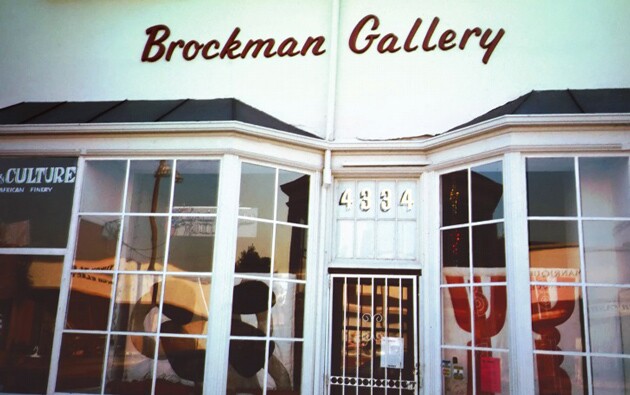

"Success always leaves footprints" is a statement famously attributed to Booker T. Washington. In 1967, two years after the Watts uprising in Los Angeles, artists and educators Alonzo and Dale Davis realized this dictum when they opened the Brockman Gallery in Leimert Park, a Los Angeles neighborhood affectionately referred to by residents as "the village." The Brockman Gallery was founded during the heyday of the so-called Black Arts movement. Though numerous galleries opened in Los Angeles and across the country in the 1960s and 1970s with the aim of advancing the notion of a black art form, the Brockman Gallery -- a commercial gallery in the midst of community focused ventures -- was unique for the time period. Through their gallery Alonzo and Dale Davis provided early exposure to a number of artists who today are widely acclaimed, including Betye Saar, David Hammons, and John Outterbridge.These artists, along with other Southern California artists of the era, were included in the notable 1989 exhibition "19 Sixties: A Cultural Awakening Re-evaluated,1965-1975." Recently, a renewed interest in black Los Angeles artists active from the mid-1960s to the late 1970s has spawned their inclusion in a variety of noteworthy exhibitions.

Growing Up in the 'Old South'

Alonzo and Dale Davis grew up in Tuskegee, Alabama, a small southern community of self-made residents not necessarily tethered to the more traditional jobs held by blacks in larger northern or western cities. The history of entrepreneurship among African Americans is inextricably intertwined with the history of segregation and Jim Crow laws, which limited black people's mobility and restricted their access to services. As children, the Davis brothers were greatly influenced by the pervasive attitude of self-reliance that was commonplace in the tight-knit college community where they lived. Higher education and self-sufficiency were highly valued at Tuskegee Institute, a place where one could witness numerous manifestations of black achievement. Founded by Booker T. Washington, Tuskegee Institute was a model institution held up by the U.S. government, as well as major corporations, to illustrate that blacks could excel in American life if given the opportunity -- even under segregation. Despite a dark smudge on its history -- the notorious syphilis experiment executed in the 1930s by the US government 1 -- the institute became world-renowned as the training ground for the Tuskegee Airmen, another government-sponsored experiment, and served as a bastion of higher education and an example for the many dignitaries from different parts of the world, especially those from African and Caribbean nations, who made frequent trips to the campus.

Alonzo Davis was born in Tuskegee in 1942, just one year after the famed Tuskegee Airmen took to the air. 2 Dale was born in 1946. The Davis brothers grew up on Bibb Street in a community of educators who worked at the institute. Their father taught psychology, and their mother was a librarian at the college library. During the final years of the war, the boys left Tuskegee for St. Paul, Minnesota, where their father completed his Ph.D at the University of Minnesota. When they returned to Tuskegee, their father was made dean of the Education Department. Alonzo remembers a childhood of privilege, summers spent lying in the shade of a stretching magnolia tree in the mid-1940s in front of his house, participating in campus-sponsored activities such as swimming and tennis, and lounging on the flat clay soil at Dead Man's Peak, a popular meeting place for the community children. Renowned entertainers and other luminaries frequently visited the campus. The institute was an insular community, aware of but situated away from the demeaning Jim Crow laws in the town of Tuskegee.

When asked about the influences that contributed to his artistic and entrepreneurial sensibilities, Alonzo recalls that his first job was collecting and selling pop bottles back to the Flakes Store and coat hangers to Reid's Cleaners. On Saturday mornings Dale worked at sweeping out Le Petite Bazaar, the small women's clothing shop owned by Mrs. Dawson, the wife of William Levi Dawson (1899-1990), the celebrated composer, choral conductor, and professor. Dale also liked fishing and befriended local fishermen, selling them worms and crickets so that they would take him out with them. Away from his friends, Alonzo grew zinnias because he liked their bright colors. His friends teased him when they found out, so he began tending his zinnias on his way to play baseball -- a move that quelled some of the teasing. Working with zinnias made Alonzo more interested in color and inspired him to take art classes from Elain e Freeman (Thomas), who later became chair of the Art Department at the institute. Freeman's father, who was paralyzed, painted with his toes. Alonzo and Dale often visited Freeman's family home to look at his work and watch him paint. Alonzo remembers his most rewarding art experience taking place at the institute's Chambliss Children's House School, an elementary school where practice teachers taught classes on everything from drawing to gardening to the children of the institute's employees as well as the townspeople's children. Winning an award there for a landscape painting encouraged Alonzo to pursue art.

For Alonzo, artistic endeavors were just another part of an active childhood, mixed in with the 4-H Club, the Boy Scouts, and Saturday-morning visits to the ROTC shooting range to fire a .22-caliber rifle. His schedule of varied activities was typical of most institute boys in this academic yet rural environment, often described by the college staff as "a ship in a rural sea." Alonzo and Dale also had many experiences unheard of for other black youth.

By the time Alonzo was ten years old, the Tuskegee Airmen had made a name for themselves, and he was taken for a ride in a Piper airplane flown by Charles "Chief" Anderson, famous as the first instructor of the Airmen and for taking First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt for a plane ride in 1941 (Alonzo boasts that since then, he's never feared flying).

Because their father held such an esteemed position at the institute, Alonzo and Dale had ample opportunities to meet dignitaries and be exposed to people from the African and black diasporas. Visits from these international figures often resulted in invitations for students from their home countries to study at Tuskegee, so the Davis brothers were accustomed to mingling with foreign students from a young age.

In addition to their exposure to people from the African and black diasporas, the Davis brothers met members of Tuskegee's Jewish faculty, many of whom had fled the Nazis before settling in the United States. Historically black colleges and universities worked with various organizations to place recently emigrated Jews in colleges and universities around the nation, regularly opening their doors to the displaced scholars. This was especially evident in the art departments on these campuses. Artist and art historian Samella Lewis has discussed the important role played by Viktor Lowenfield in the art department at Hampton University in Virginia, and artist Mary Lovelace O'Neal has likewise stated her respect for Ronald O. Schnell, who was recruited from Stuttgart, Germany, in 1959 to the art department at Tougaloo College in Jackson, Mississippi.

At Tuskegee Institute, a diverse group of writers, musicians, and other creative people visited and worked on the campus, including Dawson, who Alonzo insists made him "listen to another voice," the creative voice in his head. Alonzo came to view Dawson as a kindred spirit, someone who understood "creative spirits -- those of us who were into other things besides baseball and football." He continues, "I wasn't academic in the way my dad was, and Dawson picked up on that right away."

Like one of his friends, the painter Aaron Douglas, Dawson was interested in the development of African American musical forms. His Negro Folk Symphony had its world premiere under the direction of Leopold Stokowski conducting the Philadelphia Orchestra in 1934, the same year that Douglas painted his Aspects of Negro Life murals at the New York Public Library's 135th Street branch in Harlem. Both composer and artist explored parallel themes in these works. Dawson's symphony was composed of three symphonic movements ("The Bond of Africa," "Hope in the Night," and "O Let Me Shine"), while Douglas's mural consisted of four oil-on-canvas panels ("Aspects of Negro Life: The Negro in an African Setting," "An Idyll of the Deep South," "From Slavery through Reconstruction," and "Song of the Towers").

Influenced by the nationalistic views of Anton DvoÅ?ák, Dawson traveled to West Africa in 1952. His exposure to African music inspired him to revise his symphony to include African rhythms. 3 Dawson's interest in African culture was proudly displayed in his home, just a few houses down from the Davis home on Bibb Street. There the Davis brothers enjoyed Dawson's personal collection of African and African American art, including works by Douglas, August Savage, and Hale Woodruff. Beyond their neighborhood the Davis boys had several other opportunities to view artwork, from the George Washington Carver Museum (named for the famous scientist and artist who was an important presence on the Tuskegee campus) to Lifting the Veil of Ignorance, Charles Keck's monumental public sculpture of Booker T. Washington with a kneeling former slave. "One of my most memorable experiences was spending time in the George Washington Carver Museum looking at the brightly colored vials containing samples of his experiments and displays of his work," Dale remembers. 4 A local gallery specializing in ceramics -- a medium that would become an early focus for Dale's art practice -- also fueled the brothers' desire to pursue art.

In 1956 Alonzo and Dale's parents separated, and the boys took the Super Chief passenger train from Chicago to Los Angeles with their mother. In 1948 restrictive real estate covenants had been lifted in Los Angeles, allowing black people to buy property west of Western Avenue. The Davis family did so, though moving into the new neighborhood was a cultural shock for the brothers. In Tuskegee the Davis brothers had lived in a closed community of black educators. The area where their family settled in Los Angeles was much more diverse. Alonzo remembers the student population at the new school: "It was comprised of black kids whose fathers worked at the U.S. Rubber Company, white kids [whose] parents worked at USC and wanted them to 'toughen up' in public school, and Japanese kids [who] had been in internment camps." 5 In Los Angeles the Davis boys were exposed to a more racially diverse group of children than they had experienced in the predominantly black and insular Tuskegee.

Both of the Davis brothers entered and graduated from colleges in Los Angeles. Alonzo remembers that while in college they never learned anything about Africa or African Americans. For them, the seeds of their African heritage -- a heritage that would later inform the naming of their gallery -- had been firmly planted during their youth in Tuskegee. "We had spent our formative years in what people now refer to as 'the Old South' -- Birmingham, Montgomery, Atlanta, and Durham, North Carolina. These were places we visited with our family, and even though young, we were very aware of the issues of segregation confronting the South," says Dale. 6 By the time they began giving serious thought to opening a gallery, Alonzo had graduated from Pepperdine University, and Dale was an art student at the University of Southern California.

In 1966 they embarked on a cross-country road trip along I-20 in a Volkswagen Beetle, stopping off to visit with local artists along the way. Reconnecting with their southern roots, they visited colleges and universities, found vibrant art programs, and talked to students and faculty. In Washington, D.C., they met Topper Carew, who opened the New Thing Art and Architecture Center in the late 1960s. Carew inspired the brothers' vision of a gallery as a place to at once enliven the black community and generate revenue. Before leaving the East Coast, they drove to Philadelphia and met with Romare Bearden in New York City, circled back to upstate New York, and continued into Canada, returning to the United States through Detroit. They returned to Los Angeles in 1966 after participating in the Meredith March, billed as "a march against fear," which Alonzo says "test[ed] [our] resolve and commitment to be a part of a national response to the racism issues of the time." 7 Within nine months of returning to Los Angeles, Alonzo and Dale found a building in Leimert Park Village. After talking with family members, who discouraged the brothers from doing it, they spoke with a lawyer and leased the building. While the brothers both taught art in high school, their main focus was on opening their gallery. Alonzo was twenty-four and Dale was twenty.

The Village

Opening in a location on Degnan Boulevard, the main commercial strip in Leimert Park Village, the Davis brothers felt that they had secured a commercially viable space in a growing black community. Leimert Park is a village at the foot of the "Hills" -- including View Park, Baldwin Hills, and Windsor Hills -- which offered sweeping views of the Los Angeles basin and the Hollywood Hills to the east and the north, as well as Marina del Rey, Venice, Santa Monica, and Malibu as they stretched to the Pacific Ocean on the west. Leimert Village, with its small triangular park at 43rd Place, is one and a half miles square, bordered by Crenshaw Boulevard, Leimert Boulevard, 43rd Street, and 43rd Place. The village was developed by Walter H. Leimert in 1928 and designed by Olmsted and Olmsted, brothers and sons of Frederick Law Olmsted (1822-1903), one of the two designers of Central Park in New York. They designed two-story Mediterranean-style buildings -- a favored style for many communities in Los Angeles -- for the commercial strip running through the center of the block.

Leimert envisioned his village as a self-sufficient community for upper-middle-class families with comfortable accessibility to schools and churches. The tree-lined streets and hidden utility lines created an oasis -- an ideal atmosphere for families. It was no secret that a legal provision forbade selling property in this ideal family enclave to black families. In 1947 the neighborhood made headlines when the bisected and mutilated body of Elizabeth Short, the victim of the notorious Black Dahlia murder mystery, was found in a vacant lot in the 3800 block of South Norton Avenue. The area was in the news again one year later in 1948, this time for the lifting of the racially restrictive covenants that had prevented blacks from moving to the neighborhood. Free to move farther west, black middle-class families began settling between Western Avenue and Crenshaw Boulevard, soon to be a core area of black business achievement of the sort that was previously found near Central Avenue. Wealthy black Angelenos gravitated to Leimert Park and to the Hills. Leimert Park Village became one of the first communities in Los Angeles to have a homeowners association. To maintain an integrated community, blacks and Asians -- with a few whites -- founded the Crenshaw Neighbors Association in 1964. The Davis brothers believed that this community of black wealth was ripe with patrons for their gallery. As more black families moved into the area, whites moved farther west.

In 1965, a few years before the Brockman Gallery opened and in the midst of increased white flight, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) separated from the Los Angeles County Museum of History, Science, and Art (founded in 1913) on Exposition Park and moved to the Miracle Mile neighborhood on Wilshire Boulevard. This left many blacks with few options to see and experience fine art from other parts of the world. LACMA's move to Wilshire Boulevard meant that most of the communities of color that encircled Exposition Park had to travel farther to see artwork. Residents of communities in the Hills, many of whom were already patronizing shops on the far west side of Los Angeles, generally embraced the move.

The homes in this tree-lined neighborhood -- typically furnished with Provençal furniture and grand pianos -- created a comfortable environment for wealthier blacks, in stark contrast to life in the sprawling black communities farther east and south in Los Angeles. Before the Davis brothers embarked on their cross-country journey, in 1965 the Watts uprising erupted, and the National Guard set up a no-cross line on Crenshaw Boulevard at the foot of the hill communities. The residents of Leimert Park, situated on the east side of Crenshaw Boulevard, must have felt a pronounced sense of vulnerability. Alonzo was in Europe, sitting in a Paris café, when he heard about Watts. He recalls people he met in Paris asking him: "You're from Los Angeles. What are you going to do about this?" 8

In retrospect, Davis observes that it was for the best that he wasn't there at the time, since he was "hotheaded" and likely would have found himself in trouble. Of course, he knew many artists who actually lived the experience, watching Watts and South Los Angeles burn as fires continued to spread, with no end in sight. Many artists were livid about the destruction, the police brutality, and the poverty that sparked the uprising, and in the aftermath of the rebellion their frustrations manifested in their work. The Davis brothers met a number of these artists before the uprising -- including Noah Purifoy, Judson Powell, and John Riddle -- when their work was exhibited at the Watts Recreational Center, the site of the Watts Summer Arts Festival.

Alonzo met artist Dan Concholar in a park where he often went to read. With so many contacts in the arts scene, a lack of local venues in which to experience art (resulting from LACMA's move), and the artists' passionate desire to do something in the aftermath of the Watts uprising, the Davis brothers had all the motivation and resources they needed to open the Brockman Gallery. Alonzo notes: "After the Watts riot, there were a lot of artists doing works that were politically significant. They were making statements that were social. We filled a gap and a void there. We just opened a window that had never been available, especially on the West Coast." 9

The Brockman Gallery opened in 1967 at 4334 Degnan Boulevard in the center of the Leimert Park Village shopping district. The gallery was named after the brothers' grandmother Della Brockman, whose maiden name was also Dale's middle name. Della Brockman's father was from Charleston, South Carolina, and was of mixed race, the child of a white slave master and a black female slave. He was indentured, and when he left the plantation, he married a Cherokee woman in the Charleston region. The family has never been sure why, but it is known that he eventually returned to the plantation. In the late 1960s, as blacks and African American organizations actively adopted African names, the Davis brothers decided to use the name Brockman in honor of their great-grandfather, the mixed-race slave who married the Cherokee woman. By celebrating their southern roots rather than their more distant African ones, they hoped to display that they were comfortable with their family's history and felt no need to deny their slave and racial heritage. Such an outright embrace of a slave name ran counter to the position of some black nationalist groups. "When we adopted Brockman as our name, we took heat [for the] slave name because it was a time of Black Nationalism in Los Angeles. We were respected [for our efforts] but we had a slave name," recalls Alonzo.

Starting the gallery in 1967 was not easy. Alonzo was teaching art at Manual Arts High School in South Los Angeles on Figueroa Boulevard, less than fifteen blocks from where Dale was completing his undergraduate degree in art at the University of Southern California. Recognizing a need in their community and driven by a longing to go into business for themselves, they established the gallery as a private enterprise rather than a nonprofit entity. Even though they were community-minded, they viewed this opportunity as a career path and from the beginning focused on selling art as a commercial venture. They joined the Art Dealers Association of Southern California and received help and ideas from the professional organization. A number of people in the art business at that time were members of the Jewish community, and they wanted to see Brockman Gallery succeed. One such person was Benjamin Horowitz, who founded the Heritage Gallery on La Cienega Boulevard in Los Angeles and was well known to the Davis brothers because of his early promotion of works by Charles White, David Alfaro Siqueiros, and Jose Clemente Orozco. In 1965 Horowitz authored Images of Dignity: The Drawings of Charles White, a text that helped make Charles White wildly popular. 10

Another of Alonzo and Dale's allies was Joan Ankrum, founder of the Ankrum Gallery, established in 1960 (to 1990), also on La Cienega. She showed the work of Bernie Casey

for many years. Both Horowitz and Ankrum sensed that while the Davis brothers lacked a working understanding of the art business, they possessed a strong desire to fill a void in their community. Alonzo and Dale also credit William "Bill" Pajaud, artist and curator of the Golden State Mutual Life Insurance Art Collection, as an "active participant in the growth of our experience as gallerists -- he was very focused on our contributions [to the black arts community] and challenged us to maintain a very professional business model -- Bill was [a] dynamic and forceful challenger," according to Dale. Alonzo remembers, "[We] learned by the seat of our pants -- bookkeeping, consignment, and setting up a business account, sales and recordkeeping -- [we] had no formal education." Both brothers contributed to the daily management of the gallery, including conceptualizing and implementing the diverse programming that became a signature of the Brockman Gallery.

Alonzo and Dale found themselves caught between the model of community involvement embodied by Topper Carew and the strictly business model informed by lessons they were learning from other art dealers. Shortly after the Brockman Gallery opened, Suzanne Jackson opened Gallery 32 on North Lafayette Park Place near MacArthur Park and the Otis and Chouinard Art Institutes, not far from downtown Los Angeles. Jackson's approach to running a gallery differed from the approach favored by Alonzo and Dale Davis. Her gallery, much like Carew's space, was a vehicle for community activism and change, a place where artists gathered to discuss politics and society. As young entrepreneurs running a for-profit business, the Davis brothers made difficult business decisions that some community-minded artists did not favor. Frequent comparisons were made between the commercial example of the Brockman Gallery and the nonprofit example of Gallery 32; the former was often derided for pursuing a business model, while the latter was celebrated as a site where social change could be effected. Despite such criticisms, the Brockman Gallery hosted the Black Artists Association (BAC), offering a forum for dialogues on the work of black artists. Nevertheless, the Davis brothers experienced some backlash from artists represented by the Brockman Gallery who felt that Alonzo and Dale were taking advantage of them.

Some artists believed that the brothers should share more of their profits. Artists who thought that they should receive more than the standard percentages that other art dealers were awarding began to sell their work independently of the Brockman Gallery, although the Davis brothers continued to promote the artists' works. Some artists, however, were endowed with a keener understanding of the art world and the challenges faced by the Brockman Gallery; in any case, the Davis brothers had no shortage of talent to represent. John Outterbridge recalls many of the artists who came through the Brockman's doors, including Timothy Washington, Ruth Waddy, and Samella Lewis. Lewis and fellow artist Bernie Casey also founded Contemporary Crafts Gallery in 1970, and Lewis opened the first African American-owned art book publishing house, Contemporary Crafts Publishers, Inc., in the gallery.

As a result of the Watts rebellion, more attention was focused on LACMA's need to service a broader community with its programs. In 1968 the BAC, founded by its black employees, advocated for and organized a black cultural festival in conjunction with the exhibition "The Sculpture of Black Africa: The Paul Tishman Collection." In 1972 Robert Wilson became their first black board member, and in 1976 LACMA became one of the first museums in the country to organize an exhibition of the work of African American artists: "Two Centuries of Black American Art," curated by artist and art historian David Driskell. Also in 1976 Samella Lewis founded the Museum of African American Art in the May Company Department Store building on Crenshaw Boulevard, just blocks from the Brockman Gallery, and the California African American Museum, chartered by the state in 1977, opened its doors in its new forty-four-thousand-square-foot building designed by black architects Jack Haywood and Vince Proby during the 1984 Summer Olympic Games in Exposition Park, the same park where LACMA once operated.

These new institutions signaled the promise of a healthy black cultural scene for Los Angeles. After opening the Brockman Gallery, Alonzo left his high school teaching job to enter graduate school at Otis Art Institute. Though it had been difficult to sustain the business, the Davis brothers calculated that by 1970 the gallery could survive on its own. But the challenges from the black arts community continued to swell, ultimately obstructing the brothers' desire and ability to fully implement the business model they had developed. Finally, they decided to form a nonprofit. As a nonprofit, the Brockman Gallery could receive grants from the city, state, and federal government for programming and educational projects. While the Brockman Gallery focused on exhibiting artwork for sale, Brockman Productions was established to address the social and artistic needs of the community. Brockman Productions received funding for film festivals notable for a number of important screenings, including "Child Resistance" by UCLA film student Haile Gerima, and one of the earliest screenings of Larry Clark's film "As Above, So Below."

In the 1970s Brockman Productions screened the films of UCLA film student Ben Caldwell. Caldwell and fellow film student Charles Burnett, director of "To Sleep with Anger," joined forces to focus their cinematic attentions on L.A.'s black communities, setting up shop in Leimert Park Village. With other creative professionals moving into the area, the neighborhood soon became a black cultural Mecca. The Brockman Productions mural program included muralists such as Richard Wyatt, Judy Baca, Kent Twitchell, and Frank Romero. The Brockman music component introduced the music of instrumental group Hiroshima and offered frequent music happenings with Horace Tapscott and the Pan Afrikan Peoples Arkestra at free concerts. When the Brockman Productions programming became successful, the Brockman Gallery began to attract emerging artists from other parts of the state and beyond: Mildred Howard, Carrie May Weems, Joe Sam, Maren Hassinger, and Martin Payton, among others. Many established black artists also exhibited there, including Elizabeth Catlett, Charles White, John Biggers, Jacob Lawrence, and Romare Bearden. Dale attributes Brockman's success as a nonprofit to a cultural shift that offered new, broader opportunities to cultural centers in the area. The Davis brothers' exposure to art and culture as young children impacted their view of the art world, their sense of aesthetics, and their investigations beyond image-based art. In the gallery, they offered high school and college students internships to help them learn the business of art and become familiar with some of the issues associated with community-based and for-profit galleries.

Initially, events put on by Brockman Productions were not actively promoted; the Davis brothers mistakenly thought that they were in a financially stable neighborhood and assumed that if they developed events, the population in the Hills and beyond would support them. However, the wealthier Hills residents were looking westward, and that is where their income went.

Though some collectors purchased from the Brockman Gallery and attended Brockman events, their support was limited. Realizing that they could not rely solely on the black community to sustain themselves, Alonzo and Dale expanded their support base, reaching out to Hollywood and Jewish communities that in turn brought in another group of clients and made residents in the Hills community more responsive. Like Gallery 32, the Brockman Gallery featured black artists -- though not exclusively. To expand their support base, the Davis brothers also featured Hispanic, Anglo, and Japanese artists who had grown up in the area and had gone to school there and were still part of the surrounding community. While Alonzo was at Otis, he convinced his artist colleagues to exhibit at the Brockman Gallery, which was viewed as an alternative exhibition space. Because of the diverse roster of artists promoted by the Davis brothers, a community joke circulated that the Brockman Gallery showed non-black artists more than the white galleries showed black artists.

After Dale married in 1980, he became less involved at the gallery. Though he continued to marginally participate in gallery activities, he became much more active in the nonprofit side of the business, Brockman Productions. Later Alonzo left the for-profit side of the gallery in 1987 to become the interim director of the public art program for the city and county of Sacramento:

Part of leaving Los Angeles and relocating to Sacramento was trying to find my identity as an artist and move from other artists pulling at me, wanting more of my time and resources for community-oriented programs -- [as an artist] I wanted to do my own thing. The community was so hard and expectations were so great and you were only seen in one direction and not as a multi-directional person -- it just wasn't working.

Debbie Byars, a former student of Dale's, became acting director while Alonzo was away. As an artist and administrator, Alonzo continued to pursue his personal interests. After his stint in Sacramento, he was awarded a six-month fellowship at the East/West Center in Hawaii. On his return, Alonzo realized that the gallery was failing and that his and Dale's interests lay elsewhere. In 1990 they decided to close the gallery. They turned over their lease to Mary and Jacqueline Kimbrough, who opened Zambezi Bazaar. Mary and Jacqueline come from a politically active family and, along with their brother Alden, collect books, ephemera, and recorded music, as well as many other objects that help tell the story of blacks in America. At the time, the Brockman Gallery consisted of four storefronts: for twenty years the Davis brothers had worked to build an artistic village, and they had several artist-in-residence spaces. Dale remembers their creation as an icon of cultural pride, entrepreneurship, and the power of vision, common purpose, and determination.

In the 1990s, just after the Brockman Gallery closed, "the village" experienced a cultural rebirth, with new businesses popping up in Leimert Park. Along with the Kimbroughs' Zambezi Bazaar, the new crop of businesses included Brian Breye's Museum in Black (specializing in the exhibition and sale of African art and artifacts and of black memorabilia), Marla Gibbs's Vision Theatre Complex (formerly the Leimert Theater, built in 1930 as a joint venture between Walter H. Leimert and Howard Hughes), Gibbs's Crossroads Art Academy (a provider of arts programs for youth), Babe's and Ricky's Inn (a club that relocated from Central Avenue to the Village), Kaos Network and Project Blowed (which offered creative adults and young people a meeting place and focused on new media technology; it was created by Ben Caldwell, who had worked at the Brockman Gallery in the 1970s), and Kamau Daaood's World Stage (a venue for spoken word readings, jam sessions, workshops, and performances, founded in 1989 by drummer Billy Higgins). The Pan Afrikan Peoples Arkestra, established in 1961, continued to be an active cultural presence in the village.

Although homeownership in Leimert Park remains high, many businesses in the village, a

prime piece of Los Angeles real estate, are leased. Village rents steadily rose, and many businesses lost their leases between 2000 and 2010. New cultural footprints have begun to take hold in the area. Artist Mark Bradford has opened a street-level storefront studio in Leimert Park on the site of his mother's hair salon (where he was a stylist before going to art school at the age of thirty). In 2010 Eileen Harris Norton founded the Leimert Project, a promising new space, next to the Zambezi Bazaar in one of the same storefronts occupied by the Brockman Gallery during its years on the block. 11

Today Los Angeles is experiencing a resurgence of interest in its art scene, and artists every-where -- including black artists -- increasingly participate in a transnational art dialogue. Decades ago Alonzo and Dale Davis planted an entrepreneurial cultural seed that continues to manifest in Leimert Park Village. That seed germinated many miles away in a small, predominantly black college community founded on Booker T. Washington's affirmation of the virtue of self-reliance, a notion that was reinforced by the boundaries of racial segregation. Though society has come a long way since the days of Jim Crow, the story of the Davis brothers reminds us that it is more important than ever to acknowledge how viable community examples and business models can nurture desired outcomes and affect the way a community thinks about itself.

Author's Note

Although Alonzo continued his art practice, it has suffered due to the time he has devoted to running a private gallery. After closing the gallery, he reestablished himself as a visual artist without, as he says, "having the chain of the gallery holding me down." He was an artist-in- residence at Lawrence University and then became a visiting artist at San Antonio Art Institute in Texas before taking a position from 1993 to 2002 as academic dean at the Memphis School of Art in Tennessee. He had gained a great deal of business and nonprofit work experience with the Brockman Gallery, so arts administration was an easy transition, and he was at ease in a creative environment where fresh and innovative ideas could flourish without the restrictions of racial expectations. He has also been a fellow several times at the Virginia Center for Creative Arts and now serves as one of its advisers. After leaving Memphis he continued his entrepreneurial activities, opening his own artist residency, AIR, in the artist community of Paducah, Kentucky. Most of the year he spends his time in his studio at Montpelier Art Center in Laurel, Maryland, and he exhibits widely. Dale still resides in Los Angeles, not far from Leimert Park Village and the site of the former Brockman Gallery. Dale taught art at nearby Susan B. Dorsey High School in Leimert Park until he retired from teaching in 2002. His mixed-media art practice has continued without interruption, and he is exhibiting more due to the renewed interest in LA artists. He also continues to be involved with Brockman Productions as a board member.

____________________________

Notes

1 In 1932 the US Public Health Service and the Tuskegee Institute

enrolled four hundred poor black men in a project to study untreated syphilis, known in the local community as "bad blood." The men actually had syphilis.

2 According to the Tuskegee Airmen website, "The black airmen who became single-engine or multi-engine pilots were trained at Tuskegee Army Air Field (TAAF) in Tuskegee, Alabama."

3 See Eileen Southern, The Music of Black Americans: A History (New York: Norton, 1983), 419. Dawson knew Douglas, and when I visited Dawson in the early 1980s, he had examples of Douglas's art in his home. Southern states, "According to the composer, a link was taken out of a human chain when the first African was taken from the shores of his native land and sent into slavery."

4 Dale Davis, pers. comm., February 28, 2011. Additionally, George Washington Carver, the scientist and artist, is known for his cultivation of amaryllis bulbs, which he shared with the institute community. He also developed printers ink from surplus

peanuts. The ink was of particular interest to the campus print shop.

5 Alonzo Davis, interview by author, March 27, 2011.

6 Dale Davis, "Brockman Gallery," photocopy, February 2011.

7 The Meredith March was named after James Meredith, who in 1962 became the first black student to attend the University of Mississippi after federal courts ruled that blacks could not be denied entry based on their race. Meredith continued his graduate studies at Columbia University, and on June 5, 1966, he and a few companions began a "march against fear" walk from Memphis, Tennessee, to Jackson, Mississippi, to register black voters. On June 6 he was wounded by a shotgun blast.

8 Alonzo Davis, interview by author, March 27, 2011.

9 See Jeannette Lindsay, dir., Leimert Park: The Story of a Village in South Central Los Angeles, 2006.

10 See Heritage Gallery, www.heritagegallery.com/horowitz.obit.html (November 23, 2011).

Special Thanks to Duke University Press. You can find the article in its original form here:

Lizetta LeFalle-Collins, "Planting A Seed: The Brockman Gallery and the Village," in Nka: Journal of Contemporary African Art, Volume 3, no. , pp. 4-15. Copyright, 2012, Nka Publications. All rights reserved. Republished by permission of the copyrightholder, and the present publisher, Duke University Press.