Three Waves of Little Tokyo Redevelopment

There's a large parking lot located on Second Street between Los Angeles and San Pedro Streets in Little Tokyo; five years from now, it will be the center of a major shift in the culture of the neighborhood. Owned by a mix of private development companies and the City of Los Angeles, the property will complement its neighboring condominiums with new units for housing and shops to pick up foot traffic.

Directly across from the parking lot will sport the fruits of the community's 30-year effort to build the Budokan, a multi-use athletic center that will serve the residents of Little Tokyo and beyond.

These two projects represent the dual interests in the history of redevelopment in Little Tokyo: the needs of the local, predominantly Japanese-American community on one side; outside interests on the other.

Yet outside interests don't always derive from very far. To long-time residents of Little Tokyo, particularly those with roots in community activism, there's been a pattern: each time the City of Los Angeles plans to expand or add new municipal buildings to the adjacent Civic Center District, they reach for property in Little Tokyo -- beginning most notably with the 1952 construction of the Parker Center Building on Los Angeles Street at First Street, which razed an entire block of residential and commercial buildings in Little Tokyo.

The seeds for this pattern were laid during World War II, aptly described by many as the first wave of Little Tokyo redevelopment history. When all persons of Japanese ancestry in the city were evacuated and imprisoned in war relocation camps, much of their property was seized by the city, as well as grabbed by African-Americans who briefly turned the area into Bronzeville.

The successive waves of redevelopment that followed reflect a complicated relationship between urban renewal and Japanese American identity. Development beginning in the 1970s involved compromises between Japanese corporate developers, community leaders, and the City of Los Angeles. Stakeholders in Little Tokyo struggled with the overwhelming financial power of outside players, such as the Kajima corporation (who built the Kajima Building on San Pedro Street), that challenged the community's identity which historically had been shaped by the immigrant experience.

Fortunately, by this time, lessons learned from the first wave of redevelopment had equipped activist groups in Little Tokyo with the tools and skills to campaign for local interests. The Little Tokyo People's Rights Organization (LTPRO) and the Little Tokyo Service Center, for instance, were prominent voices that addressed the needs of the residential community, and the groups served to keep the city's Community Redevelopment Agency at bay and point out conflicts with Japanese investors. Much of what we physically know of Little Tokyo today was born of the era.

Currently, Little Tokyo is in its third wave of redevelopment. With revived interest in Downtown Los Angeles, the neighborhood is once again a hot topic among developers and city planners. The location of Little Tokyo alone makes it a highly desired place for developers, who see profit in the highly walkable area that is so close to public transit and the continued revitalization of downtown.

The timeline below illustrates waves of redevelopment in the Little Tokyo, including efforts from the community and its leaders and a nod toward future changes to come.

FIRST WAVE

1941 - 1945:

Japanese internment during WWII changes Little Tokyo forever, with only 1/3 of its community remaining after the war. Property acquired by the city at this time would play roles in successive wave of development.

1949:

Japanese congregation regains Union Church building at the original site on 120 San Pedro Street after several years of neglect during after WWII.

1953:

Demolition of property from the construction of the Parker Center police complex destroyed housing for nearly 1000 people and one-fourth of the district's commercial frontage. That same building is currently slated for demolition for unsafe conditions after years of decay and the police headquarters moved out decades later.

1963:

Rev. Howard Toriumi of Union Church forms the Little Tokyo Redevelopment Association (LTRA) after needing a representative body to negotiate with the city for expansion of his church to adjacent property. A at the Daruma Café located on San Pedro Street gave rise to the Little Tokyo Redevelopment Association (LTRA), an entity that, in turn, developed into the influential Little Tokyo Community Development Advisory Committee (LTCDAC), with Reverend Toriumi at the helm. Original plans of the LTRA were modest and involved transforming a an alley into a full-fledged street, repairing lights and planting trees.

Interest attracted from Japanese firms seeking to expand in to the American market and the city of Los Angeles. The Sumitomo Bank office building, the Merit Savings Bank Building, and the 321 Medical Building built by the Kajima Corporation.

1969:

Little Tokyo Community Development Advisory Committee is organized.

Plans to widen First Street through the district's historic core and to extend the Civic Center deeper into Little Tokyo. The Nishi Hongwanji Temple, founded in 1905, moves in fear of this expansion to 815 East First Street. The City of Los Angeles acquires the abandoned property.

SECOND WAVE

1970:

The Community Redevelopment Agency adopts the Little Tokyo Project. Throughout this relationship, Little Tokyo would transform for generations into what we see today. The Little Tokyo Project promised housing, a community center, office buildings and a recreational center.

The official Redevelopment Plan was adopted by the City Council; the Little Tokyo Project's boundaries extended from Los Angeles Street on the west to Alameda Street on the east, Third Street on the south, and half a block north of First Street.

1972:

The City of Los Angeles acquires the San Pedro Firm Building. The building was originally owned by the Southern California Flower Growers Inc. as a residential space for farmers in the nearby floral market that would otherwise travel far distances from neighboring counties.

1973:

The Little Tokyo People's Rights (LTPRO) formed, which challenged the ongoing evictions caused by the redevelopment that took place in Little Tokyo at the time and was made up of residents, businesses and community people. LTPRO brought community interests to the forefront of the media, so that commitments made by the City of Los Angeles and the Community Redevelopment Agency were honored.

Japan-based Kajima Corporation, one of the world's largest construction firms, created the East-West Development Corporation to oversee the developments of Little Tokyo. The company's involvement in a Chinese peasant, slave-labor camp and attacks against unions in their future L.A.-based hotel would later come to public attention.

1974:

The Little Tokyo Anti-Eviction Task Force orchestrates a protest against construction of the New Otani Hotel.

1975:

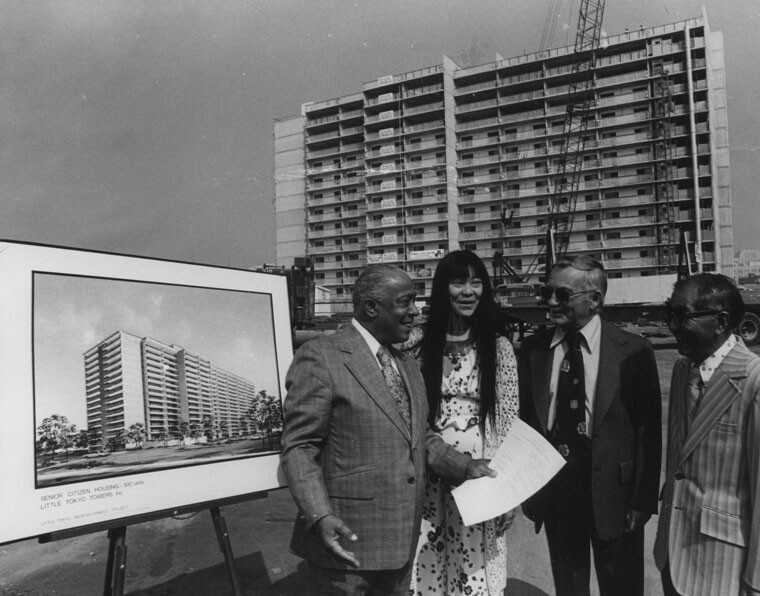

An important project for the Little Tokyo Community Development Advisory Committee stemmed from the urgent need for affordable housing for the elderly. Older generations were dying out, evicted, or living in unsafe conditions of decaying hotels. The Little Tokyo Towers was built in time to serve those facing evictions from the New Otani Hotel.

The CRA has financial trouble, and locals worry that small businesses will be

destroyed when outside developers are brought in to fund developments.

With the City of Los Angeles plans for the widening of certain sections of San Pedro Street, the congregation of Union Church weighed its options, and decided to search for a new site. The church property was sold to the City of Los Angeles, which leased the building to the Community Redevelopment Agency.

1976:

Construction begins for the New Otani Hotel and Garden and the Weller Court, which forced the closing of the Sun Hotel and Sun Building, home to many cultural and community offices in the Japanese American community; all the residents were evicted; most of the residents were Japanese American until 1972, when the majority became Latino.

The Little Tokyo People's Right Organization (LTPRO) holds a march and rally in Little Tokyo to protest the eviction of Sun Hotel resident. LTPRO members later occupy the hotel to prevent demolition but are ousted by County marshals.

1977:

Public art piece is installed in the New Otani Hotel, to fulfill a provision in the Plan for the Little Tokyo Redevelopment Project requiring developers to commit a half percent of the cost of new projects for landscaping or public art. A community based volunteer group, The Friends of Little Tokyo Arts (FOLTA), is formed to promote the integration of art in the redevelopment of Little Tokyo, which was commissioned for the next five years. Because of FOLTA, public art became a regular part of urban renewal in Little Tokyo.

1979:

Little Tokyo Service Center (LTSC) is founded by representatives of various Japanese American groups. LTSC aimed to provide linguistically and culturally sensitive social services to the Little Tokyo community and the broader Japanese American community in the Southland. The organization would later expand to serve pressing community needs like housing and play their own role in Little Tokyo's development history.

1980-1985:

The Japanese Cultural Community Center is built in several stages. It was funded by 5 sources: 1) the U.S. government through Housing and Urban Development funds; 2) American corporations and foundations; 3) Japanese government; 4) businesses under the Japan Federation of Economic Organization; 5) other sources in the Japan and Japanese corporations in the U.S.

1982:

The Japan-American Theater is completed; it was funded by hundreds of Japanese companies, organizations, and individuals. It cost $6.4 million to build: $4.4 million came in donations from the Japanese, $75,000 came from the Housing and Urban Development funds, and the rest came from local organizations.

1983:

Yagura Tower (replicates fire tower in rural Japan), built on First Street by Korean developer David Hyun, anchors the entrance to the Japanese Village Plaza that will begin a year later.

Following concerns about the World War II experience being forgotten and feeling the need for a permanent space to exhibit that information, Bruce Kaji and Nancy Araki begin discussions with veterans and interest groups to construct what would become the Japanese American National Museum.

1985:

The public art requirement is tightened when the CRA adopted a larger percent for art policy applicable to all of downtown.

The Japanese American National Museum is incorporated as a private, nonprofit institution. California State Senator Art Torres introduces a funding bill that acknowledges the major contributions Japanese Americans have made to the social, cultural and economic spheres of California, and the state legislature soon appropriated $750,000 toward the Museum on the condition that Los Angeles provide matching funds. At the urging of the volunteer corps, the City of Los Angeles granted a $1 million match the following year.

H. Cooke Sunoo, project manager in the Little Tokyo office of the city's Community Redevelopment Agency, leased the former Nishi Hongwanji Buddhist Temple building, then owned by the City of Los Angeles, for the Museum for $1 a year. He also committed the CRA to $1 million of support.

1986:

Little Tokyo is designated as a National Historic District after businesses on the north side of First Street are threatened by the city's master plan to expand the Civic Center. The CRA/LA approved loans for these businesses so that they could upgrade and improve their chances of staying in business and be included in the Historic District.

The Alan Hotel and Annex, as well as the Masago Hotel, are demolished. The

hotel was noted for housing a large population of low-income and elderly residents, and figured prominently in the alleged attempted assassination of Jimmy Carter in May 1979. The hotel was demolished in 1986 following a lawsuit demanding eviction settlements for the displaced residents.

1988:

Over 100 people -- mostly students -- come out to paint the San Pedro Firm Building on June 13, 1988. They are supervised by skilled workers from the Japanese American Contractors, who plastered and prepped the walls. A determined group of UCLA students mobilizes student groups from different campuses.

President Reagan issues reparations for Japanese American internees following a surge of activism from various Japanese American communities, including L.A.-based group Nikkei for Civil Rights & Redress (NCRR). Many individuals in Little Tokyo who received reparations donated funds to development projects in their community.

1989:

The Little Tokyo Service Center and the L.A. Community Design Center become co-owners of the San Pedro Firm Building

1991:

Grand re-opening of the San Pedro Firm Building with new owners and new purpose. The Little Tokyo Service Center sets up its first office on the bottom floor. It provides one of few affordable housing options for residents in the Little Tokyo community.

The Public Art Task Force by the Little Tokyo Community Development Advisory

Committee adjusts policies to channel community input to artists and developers.

1992:

The Japanese American National Museum is built in the former Nishi Hongwanji Temple at First Street and Central Avenue.

1994:

The LTSC Community Development Corporation (CDC), a subsidiary of LTSC founded to focus on community redevelopment, affordable housing, and the revitalization of Little Tokyo, is formed.

1998:

Union Center for the Arts is completed -- a multi-million renovation commissioned by the City of Los Angeles and managed by the LTSC.

THIRD WAVE

1999:

The Adaptive Reuse Ordinance is approved. This signaled the dramatic transformation of Downtown Los Angeles as a desirable place for development, which would inevitably trickle down to Little Tokyo considering its location in the city and downtown.

2003:

Construction of the 303-unit Alexan Savoy Condominiums begins just down the road from the first Japanese boarding home, which opened in 1888. The project is developed by Trammell Crow Residential. It signals the arrival of market rate condominiums in the area.

2005:

Metro jail proposed to be located on the corner of First and Alameda Streets. Community protests the project, which is too close to a historic Buddhist Temple and a day care center.

2008:

A coalition of intergenerational Japanese American activists working through the LTSC gains approval from the Los Angeles City Council of a memorandum of understanding to build the Budokan, a recreation center in Little Tokyo.

2009:

Little Tokyo/Arts District Metro Gold Line Station opens November 15. Anytime a major line of public transportation enters a neighborhood, development interests spike. Coupled with government incentive established by the 1999 Adaptive Reuse Ordinance, Little Tokyo is once more a major attraction as a walk-able transit village.

2012:

The decades-long relationship with the Community Redevelopment Agency ends with the announcement of its closure.

Feb 24th: The plaza located at First and San Pedro streets is named and dedicated to Rev. Toriumi for his leadership and dedicated service to the community. Although somewhat belated, it was a simple but impressive dedication to a man of whom God can say, "Well done, good and faithful servant."

2014:

Construction of the Regional Connector scheduled to begin--will be the busiest traffic hub in Los Angeles outside of Union Station.