The Other River that Defined L.A.: The San Gabriel River in the 20th Century

More than one major river has been a conduit for life in Los Angeles.

The contributions of the most celebrated waterway in the city, the Los Angeles River, to the growth of the region from a Spanish pueblo to a major American city are well documented. The slate of advocacy groups and individuals campaigning for its restoration continues to augment its cultural and historical significance to the metropolis.

Overshadowed by its famous companion watercourse to the west, the San Gabriel River has been the other major influence on the development of the region, since Father Junípero Serra founded Mission San Gabriel Arcángel along the banks of its tributaries in 1771. It was in the twentieth century that the river had its greatest impact on the cultural and economic development of Los Angeles, and ultimately shared a similar flood-controlled fate as the Los Angeles River.

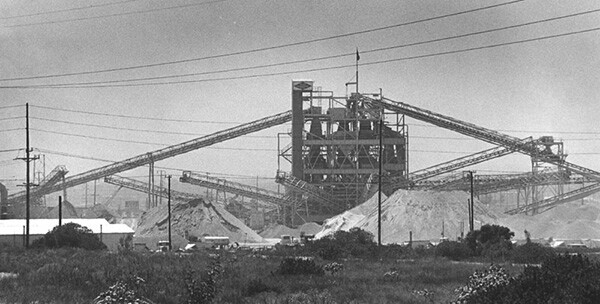

Since the early 1900s, the construction industry of Los Angeles has turned to the San Gabriel River for three very special ingredients: gravel, sand, and rock. All three sediments were in incredible abundance along the river, thanks to the rapid erosion of bedrock in the San Gabriel Mountains, which gradually deposited ten-thousand years of natural aggregate into the valley below via the river and its tributaries. The ingredients were the primary components in the industrial concoctions that Los Angeles came to rely heavily upon for the next hundred years: concrete and asphalt.

Rock, sand, and gravel from the San Gabriel River was used to construct schools, roads, freeways, and parking lots throughout Los Angeles County. The Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum and the Los Angeles Harbor were recipients of sediment culled from the depths of the river's alluvial fans. During the Arts and Crafts Movement in Southern California, contractors also eyed larger, rounded rocks for building material for Craftsman bungalows and landscapes.

It is estimated that over one billion tons of aggregate have been mined from the San Gabriel River -- one of the most important aggregate mining districts in the world -- since the turn of the twentieth century. While still a major economic force in the region, the mining operations have severely disfigured river habitats.

The other major economic force in the San Gabriel Valley in the early twentieth century was agriculture. Nowhere was the soil more fertile than on an "island" meadow in between the Río Hondo and San Gabriel Rivers that occupied the present-day El Monte. Fruit orchards and walnut groves thrived in the low-lying marshlands. Wealthy landowner owner E.J. "Lucky" Baldwin, who had owned and operated the territory since 1875, established a twenty-two acre Mexican labor camp in the area in the early 1900s. By about 1921, the encampment, often called "River Camp," began to be known as Hick's Camp, one of most famous barrios in Los Angeles County.

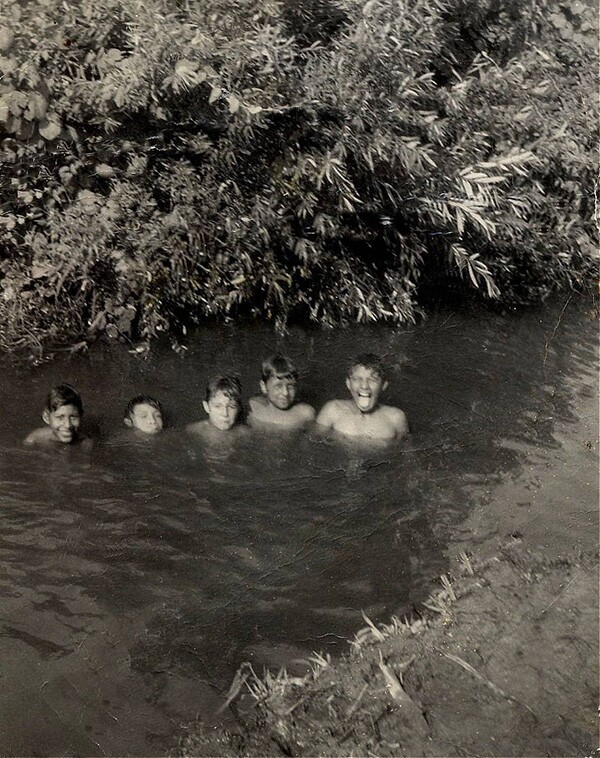

The intensive, seven-day work weeks of the families that toiled on the larger 56-acre site along the Río Hondo at meager nine cents-an-hour wages bolstered the thundering agribusiness in the Los Angeles area. "Our life was not easy. There was a lot of hard work and sweat bringing in a crop," Robert J. Bautista reflected on his boyhood in the camp in La Historia Society's 2005 "Cuentos de la Historia: The Journal of Barrio Literature and History." After a day's work from sunrise to sunset, Bautista would look forward to one of the few recreational delights in Hick's Camp:

We had the best playground in our backyard -- the Río Hondo River ran along the eastern side of the barrio. As soon as I got home, I would join my friends, who had been playing in the cool, clear water all day long...The river made our lives bearable. Our childhood along the banks of the Río Hondo River was like that of Tom Sawyer and Huckleberrry Finn along the banks of the Mississippi River.

When not serving as a playground for residents of Hick's Camp and other river communities, the San Gabriel and its weaving channels became serious hazards when they periodically overflowed their banks. Property damage and loss of life from flooding had been relatively low until the downpour of 1914. That year, developing towns that had sprouted up along the San Gabriel River in the early 1900s were at the whim of the waterway's braided series of wide channels that just a decade before would have overflowed into only sparsely populated farmlands.

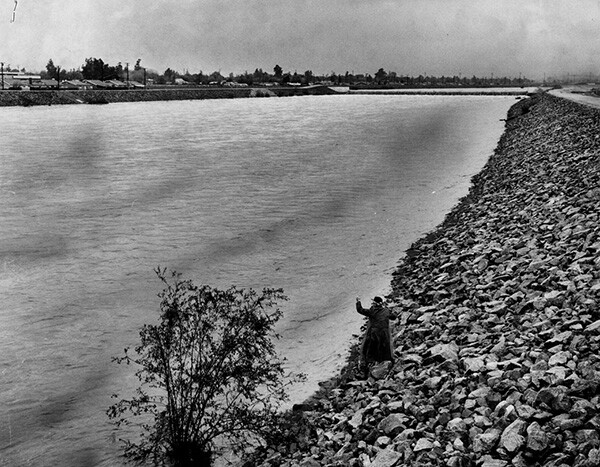

The destructive power of the 1914 flood led to an invigorated demand for flood control from civic engineers. The State Legislature adopted The Los Angeles County Flood Control Act a year later, which created a flood control district that commenced a series of measures to curb the river's unruly descent from the mountains to the sea.

But progress was not without its follies. One of the original dams to be constructed, dubbed the Forks Project Dam, was abandoned after a land slide of 500,000 cubic yards of mountainside crippled a retaining wall in September 1929. Charges of gross engineering negligence were leveled at the chief engineers, and an investigation by a grand jury concluded that bribery and corruption at the highest level of county government had occurred. County supervisor John Anson Ford admitted it was "the darkest episode" in the history of Los Angeles County government.

Despite the fiasco, a trio of dams were fitted onto the gigantic earthen foundations carved into the San Gabriel Canyon over the next two decades, and created reservoirs in the mountains. The Cogswell, San Gabriel, and Morris Dam were completed by July 1937. All three dams were fortunately operational by the time of the great downpour of February 1938. The power of the greatest flood in the recorded history of the canyon was reduced substantially by the retention of the dams, but the river did cause devastation as it jumped its banks below in the valley.

In the valley, the dedication of the Sante Fe Dam in 1946 and the Whittier Narrows Dam in 1957 would further stymie the free movements of the river. The wily watercourse was gradually sedated in the 1950s with the advent of new mechanized paving. Nearly all downstream areas would be paved in concrete. Following this operation, the Rivergrade Freeway, today known as the San Gabriel River Freeway, was finished in the 1970s, connecting Seal Beach to Irwindale on an interstate closely aligning the course of the new river.

By the late 1900s, the San Gabriel River, like its fluvial counterpart in Los Angeles, had been transformed into a defining symbol of the city's determination to annihilate flood risk from the modern era. Consequently, the twentieth century saw the river wrenched from its past as a haven of diverse riparian ecology and as a recreational oasis for river-adjacent communities.

The future holds promise, however, as organizations like Amigos de Los Rios are championing visions of restoration that may remake a healthier river for the twenty-first century.