Laws That Shaped L.A.: How the California Environmental Quality Act Allows Anyone to Thwart Development

Launched last month and posted every Monday (see archives), the Laws That Shaped L.A. spotlights regulations that have played a significant role in the development of contemporary Los Angeles. These laws - as nominated by a variety of experts we've been polling - are considered to have been either beneficial to the city or malevolent. The laws may be civil or criminal, and they may have been put into practice by city, county, state, federal or even international authority.

This Week's Law That Shaped L.A."¨

Law: California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA)

Year: 1970

Jurisdiction: State of California

Nominated by: Kevin Klowden

Remember that classic hip-hop proverb, "Don't hate the playa, hate the game"?

Well, an ill-worded (not ill-worded, alas) corollary to that wisdom once dropped by Ice-T came to mind during a recent phone conversation with the Milken Institute's Kevin Klowden.

Let's call the corollary, "Don't hate the law, hate the effect." Or, "Don't hate the law, hate the implementation." Or, "Don't hate the law, hate obstructionist opportunists with zero eco interest who exploit it."

Klowden, who is the Milken Institute's Managing Economist and Director, California Center, passed along a handful of nominations for Laws That Shaped L.A., and we'll read more from him later this year.

But perhaps the most immediately topical of Klowden's "Laws" nominations is the California Environmental Quality Act. This well-known state regulation, known by its four-letter acronym, "CEQA," - and yeah, there are four letters in both "love" and "hate" - was signed into existence in 1970 by then-Governor Ronald Reagan.

CEQA, as described by the California Natural Resources Agency website, "is a statute that requires state and local agencies to identify the significant environmental impacts of their actions and to avoid or mitigate those impacts, if feasible."

The landmark law also deputizes all Californians to assist with enforcement. "CEQA is a self-executing statute," the website text reads. "Public agencies are entrusted with compliance with CEQA and its provisions are enforced, as necessary, by the public through litigation and the threat thereof."

The four decades since CEQA's passage have coincided with** significant environmental improvements in the Golden State and beyond. That's thanks in part to development and infrastructure projects undertaken and improved due to CEQA as well as to potentially eco-harmful projects denied permission to proceed. That doesn't, however, mean CEQA is universally considered to be ideal legislation.

"There are a lot of really wonderful things about [CEQA] in terms of environmental protection," Milken's Klowden says. "But it has become in many ways emblematic of just how hostile the L.A. region and the state as a whole feel."

Klowden is articulating what are not necessarily his personal views, but rather the complaints he says he regularly hears from the business and political leaders he speaks with.

"One thing that keeps coming up with CEQA is the fact that it essentially allows anybody to use a proxy," Klowden says. "Somebody who might be vaguely affected by a development can file a lawsuit trying to block it, saying it is going to have a negative environmental impact or some sort of negative impact on them or their neighborhood or business."

The end result, Klowden says, is "there is never any real mechanism in place for mitigating those lawsuits." And so, the think tank executive says, even when developers want to improve a brownfield, they run into "all sorts of hurdles."

"It's not even an issue where people feel like the State or the City is out to get anybody," Klowden says, "It's just that it's so easy for a competitor or for somebody with some sort of rival interest to file that lawsuit and create delays and try and discourage the development and get more favorable terms or get bought off."

These and related issues are also evident in recent writings such as this L.A. Times editorial, this Downtown News op-ed by planner Joel Miller, and this The Source (Metro) post about expedited environmental review proposal, AB 1444, written by former L.A. Times writer, Steve Hymon. Curbed LA's ace editor, James Brasuell, wryly wrote of a developer comparing CEQA to terrorists and spotlightedthis. And KCET colleague D.J. Waldie wrote about NIMBYists abusing the CEQA,as well as, "Will Anyone Defend CEQA?" and won't likely be pleased with or surprised by what Kevin Klowden reports hearing.

CEQA has been particularly prominent in the news of late thanks to a pair of exemptions proffered to a pair of wealth and well-connected enterprises each seeking to build a new football stadium.

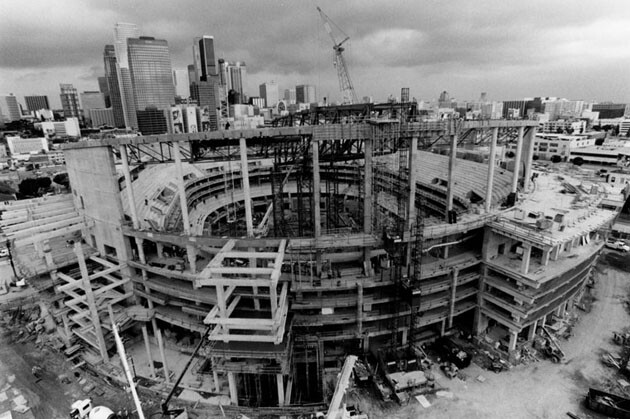

The Anschultz Entertainment Group (AEG) received a state legislature-granted CEQA expedite. Whatever a reader may think of AEG, it was hard to argue that if their similarly well-connected stadium competitor, Majestic Realty, hadn't previously received a CEQA "free pass," then AEG's competing downtown proposal shouldn't have received one as well.

Pending NFL relocations and expansions aside, how has CEQA physically shaped the city? It's hard to prove a negative. What would Los Angeles and neighboring areas look and live like without CEQA? The 710 Freeway would have gone through South Pasadena. "Swaths of the Sierra Nevada, Mojave Desert and coastline" would not have been preserved, according to an L.A. Times story last fall.

Just because a law is well-intentioned doesn't mean it's well-written. Or that after forty-plus years in existence, smart opponents and opportunists haven't figured out ways to game the law for use beyond its original environmentally-conscious intent.

"When I was growing up we used to have smog alerts all the time," Klowden says, praising green laws in general. "You don't hear about massive Stage 1 and Stage 2 smog alerts in L.A. anymore. That's great, but that's not what CEQA is. It's a completely different issue."

** Along, of course, with many other factors including other legislation such as the 1970 federal Clean Air Act, which this column will examine in coming weeks.

To suggest a Law That Shaped LA, or to suggest someone else to ask for their key law or laws, please leave a comment below, respond via Departures Facebook page and Twitter feed, or email editor Jeremy Rosenberg at arrivalstory [at] gmail [dot] com.

Top photo: Construction of AEG's Staples Center, 1999. Photo by Gary Leonard, courtesy of the Los Angeles Public Library.