Ma Maison: The Clubhouse to the Stars

Patrick Terrail was born to serve. From 1856 to 1913, his great-grandfather owned Café Anglais, a legendary, dimly lit Parisian eatery that played host to virtually all the crowned heads of Europe, as they supped in a private dining room known as "the great sixteen." His grandfather continued the tradition, first as a chef to Kaiser Wilhelm II, and then as the head of the famous La Tour d'Argent, a Parisian landmark since 1582. Numerous other family members owned and operated various eateries all over the world. They became the elite of the strange, haughty world of the wealthy servant.

Terrail grew up in the typical aspiring-aristocrat way, going to boarding school in France and spending time with his mother and stepfather in Greece. He attended Cornell University's School of Hotel Administration, and by the time he was 30, he had managed the famed El Morocco in New York, worked at the Four Seasons and managed a hotel in Tahiti. In 1970, tired of the nomadic lifestyle, he decided to settle in Los Angeles and open a classic French "bistrot." To Terrail, a perfectionist in all things, the added "t" was crucial -- he considered it the correct spelling of a word which denoted a cozy, small restaurant whose focal point was a simple menu featuring classic French cuisine.

Terrail scoured Los Angeles by foot, searching for a perfect spot. Finally, he found a ramshackle pink bungalow with an adjacent storage area at 8368 Melrose Avenue, which at the time was an unknown street slowly coming to life with antique stores and art galleries. With the help of backers, including Gene Kelly, he opened "Ma Maison," or "My House," in the fall of 1973. It received scathing reviews in the beginning, but by 1974, the jet set was finding its way to Terrail's "house." Each guest received a complimentary kir upon arrival, and the Rolls Royces and Bentleys were tandem parked in front of the rustic entrance.

Mike Fieg, a chef at Ma Maison for four years, remembers, "If you had a Mercedes you weren't good enough.They parked you down the street!"

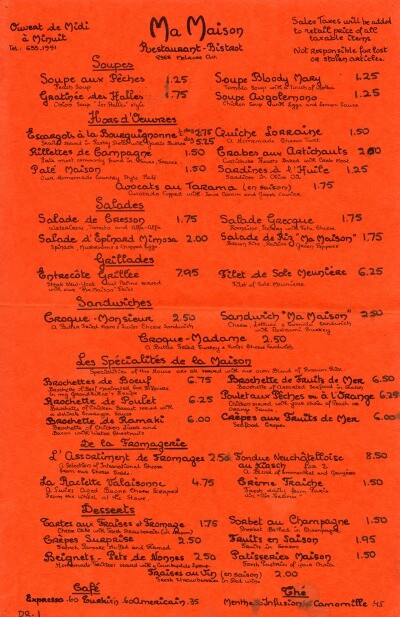

Ma Maison's quirky ambiance was a big part of its success. The phone number was unlisted. The ever-changing menus were designed by famous artists, including regular David Hockney. Eschewing the dark, wood-paneled, meat and potatoes model of "fancy" L.A. eateries, Terrail brought dining outdoors. The main dining room was the large patio, covered in Astroturf and fenced in with leafy plants that somewhat shielded the view of the adjacent parking lot. Inside the cottage was an intimate dining space furnished with thrift store finds and fine crystal, and a tiny bar with only six stools.

Another integral part of the ambiance was professional "greeter," Pierre Groleau. He was a louche, gregarious tennis nut, who, according to Fieg, "could charm a rattlesnake." Pierre brought "important" people into Ma Maison, but his sweetness was universal. "You could be homeless and Pierre would be just as nice to you," Fieg said. "He was a great guy with a big ol' smile."

But, it was the addition of the young Austrian prodigy, Wolfgang Puck, as head chef (and eventually partner) in 1975, that sent Ma Maison into the stratosphere. Terrail found a culinary soul mate in the energetic, lovable Puck. The two would get up before dawn to scour the local produce markets together. Using California's abundant goods: fresh seafood, duck, mushrooms, herbs, hybrid tiny vegetables, and virtual unknowns like goat cheese and crème fraiche, they created fresh versions of classic French cuisine and called it "California nouvelle."

Dishes like warm lobster salad, sliced duck breast, and lamb tenderloin with Roquefort sauce were revelations to palates accustomed to baked potatoes and Caesar salads.

Though he could be a "tough cookie," Terrail gave the kitchen remarkably free rein. "Use the best stuff, make the best stuff, and it better look like the best stuff," was his only rule, remembers Mike Fieg. "It was the best job I ever had."

The energy in the kitchen was electric, intense, and "a lot of fun, almost like a competition." It was a dream job for many young chefs at a time when there were few inventive restaurants in L.A. Unlike many kitchens, every day was a new culinary adventure: a vendor would drive his van up to the kitchen with fresh rabbit or pheasant, and the menu would be built around the ingredient.

Terrail also evolved a style of service all his own. He used a security camera system in his tiny office to see when regulars such as Sue Mengers, Sammy Davis Jr., Morgan Fairchild, Jacqueline Bisset, Loni Anderson, Zsa Zsa Gabor, Ed McMahon, and Cheryl Tiegs stepped into the canopied entrance so he could greet them over a loudspeaker. On Fridays, all hands were on deck for Ma Maison's famous extended drunk lunch. A group of prominent L.A. lawyers and businessmen who called themselves "the boys" would take over Terrail's private suite of French Provincial rooms upstairs, "drinking enough booze to kill a fish," playing cards and sending the kitchen into a tizzy with their demands.

Downstairs, the plastic chairs of the patio were packed with "The Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous" set. Garish, conspicuous consumption was the order of the day, with Terrail ringing a bell for the most outlandishly dressed female patron. Robin Leach himself was a regular at Ma Maison, and recalled getting busy with a lady friend at a corner table while the impeccable staff discreetly hid them from view, and then supplied a post-coital dessert.

It wasn't all caviar wishes and champagne dreams at Ma Maison. Long after the "bistrot" concept had been abandoned in favor of an expanded culinary multiplex with catering space, a pioneer cooking school called "Ma Cuisine," and a retail store reminiscent of an upscale Cracker Barrel, Ma Maison somehow retained its homey atmosphere. Terrail's "adopted mother," Suzanne Pleshette, who the staff nicknamed "Madame Gallagher," came practically every night. There was always a bottle of ketchup on hand, especially for her. At lunch, Orson Welles, dressed all in black, along with his black toy poodle, Kiki, could be found at his tucked-away table by the one-seater ladies bathroom. Welles often received his mail and correspondence in care of his dear friend Terrail.

One night would find Ringo Starr drumming with Ma Maison stemware to the amusement of Keith Moon. Another would feature a tipsy Dudley Moore serenading diners with an impromptu piano performance. Burt Reynolds and Catherine Deneuve were allegedly discovered "rehearsing" love scenes upstairs by the fireplace. Elizabeth Taylor ate on the patio while a servant held an umbrella over her head to protect her from rain coming through the patio's defective tarp.

Chef Fieg's wife, Kathy, once took her visiting in-laws to Ma Maison. They were treated to Ma Maison's VIP service, with the chef and Terrail popping over to say hello. The Feigs soon heard nearby patrons asking each other, "Who is that? It must really be somebody!" When they left the restaurant, their neighbors craned their head to get a good look. One man exclaimed loudly, "why, they're nobody!" This delighted her in-laws.

And always there was the imperious, delightful and finicky Terrail, wearing his signature red carnation in his lapel and clogs on his feet. "It is so important that a host be well dressed. A white collar is very important," he believed. "A restaurant is like a woman. It dresses up, powders -- but once in a while it gets sick," was a favorite bon mot.

Many chefs who would later become famous in their own right, including Susan Feniger, passed through Ma Maison's kitchen. In 1981, Puck left to open Spago. A year later, John Sweeney, a sous chef at Ma Maison, was arrested after the strangling death of his girlfriend, the actress Dominique Dunne, the daughter of writer/producer Dominick Dunne. Many of the Hollywood elite believed Terrail tacitly supported Sweeny, who was eventually convicted of voluntary manslaughter, and they began backing away from Ma Maison.

Though it retained its popularity until the end, Ma Maison's It status had dimmed considerably when it closed in 1985. A new Ma Maison at the Sofitel Hotel quickly failed and Patrick Terrail packed up and left his adopted home of Los Angeles. He now lives with his wife, Jackie, in Hogansville, Georgia. He runs the magazine, 85 South, which details the cultural goings-on in midwest Georgia. He seems to be at peace with his glamorous past and quite aware that lightning doesn't strike twice. "You can only run one great restaurant in your life," he has said multiple times. If anyone should know that, it would be a descendant of the house of Terrail.