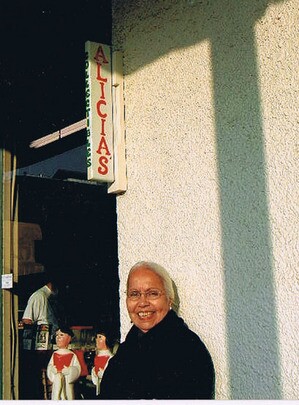

Alicia Escalante: From Texas Teenage Runaway to Leading East L.A. Chicana Activist

Each week, Jeremy Rosenberg (@losjeremy) asks, "How did you - or your family before you - wind up living in Los Angeles?

Today we hear from Alex Escalante about his mother, the East Los Angeles and Boyle Heights-based Chicano/a rights activist, Alicia Escalante

"My mother Alicia Escalante was born Alicia Lara in 1933 in El Paso, Texas to her mother Guadalupe De La Torre and Victor Lara. Alicia's mother was born in Morenci, Arizona in 1910 and her father was born in Juarez, Chijuahja, Mexico.

"Alicia was the second oldest of seven children. When her parents divorced in the early forties my mother's father won custody of all the children because he was the only bread winner. He had already remarried and was having kids again before you knew it. In the process my mother and her siblings were separated into various family/relative households.

"My mother did not like her father or uncles who referred to her mother as a whore because she had had a child from a previous marriage, which she left in order to be with my grandfather, Alicia's dad. They always held that against her. Wrongfully!

"Alicia's mom Lupe eventually -- broken-hearted -- left for Los Angeles in about 1943 to stay with her sister Aurora. She had nowhere else to go. My mother adored her mother and was very close to her. She too was heartbroken. She would miss her mother dearly, and one day decided to go find her.

"She was twelve or so the first time. She ran away from her father and his new familia and hopped a train at the rail yards. She was so small she climbed the boxcar with difficulty but managed to get in just before the train was about to leave.

"Soon the train was on its way, and all she could do was listen to the train tracks as they rolled along at full speed. She fell asleep from exhaustion and fear. She awoke to the sound of a matchstick strike and then the light, and saw there was a man in the boxcar with her as he lit his pipe. She was scared to death.

"But he was kind and asked her, 'Where you going, little girl"? And mother said, 'California to see my mom.' He told her good luck kid but you're goin' the wrong way.

"Eventually she found herself in Phoenix. Before they stopped, the man in the boxcar got up to jump out before the train stopped. He turned and said, 'I hope you find your mom.'

"When the train stopped my mother was found by the railyard man and taken into the train depot office where they contacted her father. She was sent back home to El Paso, only to leave again to find her mom when she was fourteen.

"This time her uncle Octavio, the kind one, sent her on her way by train to be with her mom. She arrived in Los Angeles about 1947. She and her mom lived in Boyle Heights on a flat above a store. Her mom worked as a waitress wherever she could in East L.A. and my mother went to school -- Belvedere, I think.

[view:kl_discussion_promote==]

"What she recalled in her early days in L.A. was that there was no smog, didn't know what the word meant. It was starting to develop but was not as bad then. She remembers the L.A. River, natural before the 1956 modernization and being able to see the mountains daily, clear skies, the Cable Cars and yes, the new styles -- clothes.

"My mother was somewhat of a tough girl. In El Paso, she and her sister Irene had been in an all-girl gang called the EPTs, for El Paso Texas. When she arrived in L.A., in school there were some locals that she had to deal with to fit herself in, so to speak. She remembers in ELA also some all-girl gangs, one of them were called the 'Black Widows.'

"The times were very hard for my mom's family. Her mom often took ill and they were eventually on welfare. My mother would go with her mom to the welfare office when needed, and she would witness the demeaning attitudes from the social workers and the humiliations her mother was subjected to. My mother soon found herself representing her mother when there was need to report to the welfare office for whatever reason. Her mom eventually came to depend on her for this.

"Soon my mother met my father, Antonio Escalante, whose family had been long established in ELA since arriving in 1918 from Arizona and Sonora before that. They had a nice little house on Concord Street in Boyle Heights, built in 1924. My father was a good-looking man -- and my mother fell in love.

"When my mother met my father, she was a fifteen-year-old girl and he was eighteen. She was impressed with him and his family as being 'well-established,' so to speak. But she happened to pick the black sheep of the bunch.

"Fast forward, my mother soon had five children by my father and he then ended up in and out of the pen. She divorced him by the time I was born in 1962 and found herself on welfare as well. Alone with five kids she ended up in the housing projects of Estrada Courts and then Ramona Gardens.

"Alicia eventually found herself in a trap of not only poverty but of oppression as well from a corrupt welfare system and whose children she struggled hard to keep from getting sucked up by the gangs and drugs that were all around.

"Her mother in 1964 passed away at age fifty-two. She was devastated. Then to top it off, at her mother's funeral the priest refused to give final prayer because her mother had disobeyed the Catholic church and divorced. The only remaining thing my mother thought she could lean on had just dropped her, like an old rag as she said.

"Also my mother had been losing her hearing for some time now, she couldn't hear planes or crumpling paper or her own kids' cries. And welfare/medical could care less.

"But there was one man, a Dr. Carlow who had an office on Whittier Boulevard in East L.A. He referred her to a specialist and friend of his. This doctor saw my mother and said he could maybe save her hearing with a new procedure. She told him she had no money and medical would not cover her. He did it for free. She never forgot him. I wish I could tell you his name.

"Amazingly my mother could hear again, clearly and so many noises she said she didn't know they existed. That's when my mom Alicia found her voice! The voice that would soon find herself getting involved with the new emerging Chicano Movement in East L.A. and in 1966, she founded the East L.A. Chicana Welfare Rights Org. And the Movement of the poor of the poor began. [Related: KCET Departures -- Brown and Proud]

"My mother fought hard for human rights and dignity for all our gente for more than twelve years. And she marched in the Poor Peoples Campaign. Was recruited by Corky Gonzales to establish WRO in Denver. Advocated and went to jail for Sal Castro in the Board sit in of `68. Was a leader in Catolicos Por La Raza in `69. Started Operacion Navidad, a local channel 34 Xmas telethon and Brown Berets were always at her back. Oh God, and the list goes on....

"My mother is losing her hearing again; she has been now for sometime. She had been told the staphs in her ears would only last about thirty years or so. She's going on eighty now and I remember many of the events I just mentioned.

"She often had me with her. She held my hand then and protected me from some scary times and I would hear her voice roar across the audiences. I sometimes have to hold her hand now and her voice has whispered. She moved mountains in those days. God bless my mother."

-- Alex Escalante

(as emailed to Jeremy Rosenberg)

Do you or someone you know have a great Los Angeles Arrival Story to share? If so, then contact Jeremy Rosenberg via: arrivalstory AT gmail DOT com. Follow Rosenberg on Twitter @losjeremy