Building Nostalgia: Disney, Legoland, and Southern California

In his review of Disney's recent hit movie Wreck it Ralph, New York Times critic A.O. Scott notes that its creators smartly appealed to the power of nostalgia. Based on the 8-bit 1980s video games of now aging Generation X -- Q-Bert, Donkey Kong, and others -- the movie appealed to "the affection parents feel for games that evoke their childhoods." The success of Ralph serves as a reminder of Disney's centrality in American post WWII life, while Disneyland itself has cast a long twentieth century shadow, repeatedly influencing suburban and urban planners as well as adults and children alike.

Few regions in America reflect this better than Southern California, and Carlsbad's Legoland provides a valuable parallel and counterpoint to its more famous Anaheim cousin. Sure, one could argue that Disney's popularity stemmed as much from merchandising and toys as its movies and cartoons, but examples like Wreck it Ralph (even if fictional) and Legoland rest on a physical participation with the actual product. Legoland is about how one feels about Legos and the ability to use them in new, yet familiar ways: even six of them can be rearranged in over 9,000,000 ways. Named "Toy of the Century" twice, Legos have cast a long shadow over the American subconscious.

Legoland opened in April of 1999, on a 128 acre seaside bluff North of San Diego in Carlsbad. At the time it represented a $130 million dollar investment by the Lego Group -- their third such development and their first in the United States. Barry H. Schoenfeld, then director of business development, noted that unlike Disneyland or Universal Studios where "the creativity of the builders is set out for you... at Legoland it's almost as if they took it so far, but the rest is up to you." In other words, what visitors put into the park would be what they got out of it.1

The most important aspect of Schoenfeld's remarks lay in issues of authenticity. Numerous writers have explored how theme parks like Disneyland try to create built environments that operate much like the stories promoted by the movies upon which they are based. As John Findley notes in "Magic Lands: Western Cityscapes and American Culture After 1940," the park's designers employed "forced perspective," scaling down, and "Disney/Capitalist" realism to promote both an "authentic" Disney experience -- one shaped by the movies that inspired it -- and the mid-century suburban ideals that Walt Disney himself supported.2

Of course, one might argue that such ideals encapsulated some of the most problematic aspects of postwar American life. Eric Avila points this out in his work "Popular Culture in the Age of White Flight," noting that Disney "renounced the contradictions and uncertainties of modern urban society. The very heterogeneity and dissonance that defined cosmopolitan urban culture inspired [him] to create a counterculture of order, regimentation, and homogeneity."3 None too surprisingly, when Disneyland opened in 1955, gender and racial equality remained distant -- and Disneyland reflected this.

Legos' own racial representations veered toward the neutral. When mini-figures first appeared in 1978, they all featured yellow skin tones; many observers suggested this was a conscious decision by the company to avoid discussions of race. In its media guide, Lego officials argued the plain yellow skin tone maintained the "non-specific and transcendental quality of a child's imagination." The release of Lego Western in 1996 resulted in its first non-white mini-figure when it included Native Americans in the new product line. Not until 2003 did Lego release more realistic mini-figures with varying skin tones more attune to reality. Yet, this development only occurred because of licensing agreements, and today, as the company's attests, "all Lego playthemes continue to use the generic yellow face." Of course, perceptive observers like Lego expert Jesus Diaz noted that the 1996 Native American example contradicted official explanations; it was a regular playtheme set rather than a specific licensing deal. Then again in the Lego world, outside of Luke Skywalker and handful of other figures, blondes fail to make the cut as well.

As a theme park, Legoland stands as the newest iteration of a SoCal tradition. California served as a pioneer in post war theme park development -- perhaps the state's greatest contribution to the tourism industry. Disneyland provided the model and replication unfolded at dizzying rates until the mid-1970s, when the market had become saturated.4 In success, they shaped the character of the surrounding areas. The aforementioned Findley notes that the very urban ills that Disneyland opposed began to develop around the park as its popularity contributed greatly to the growth of Anaheim into a city. Likewise, failure proved equally influential. As captured in the documentary "'Dogtown and Z-Boys," in the late 1960s Pacific Ocean Park descended into a post-industrial SoCal dystopia -- precariously balanced between pyromaniacs, drug addicts, and artists -- until local surfers waded out into the rebar to claim the space for themselves, and in the process went on to create a new skate culture and aesthetic.

Clearly, Legoland, built during the last throes of the twentieth century, represents a different kind of America, one not based on the rigid racial and gendered orthodoxy of Disneyland. Invented in 1958 during the rise and expansion of suburban America, Legos at first glance appear as stultifying as the suburbs to which they were largely sold: all primary colors, rectangular, and plastic. Yet, the ability of users to create almost dot matrix reproductions of realities gave them both the simplicity of youth and the complexity of adulthood.

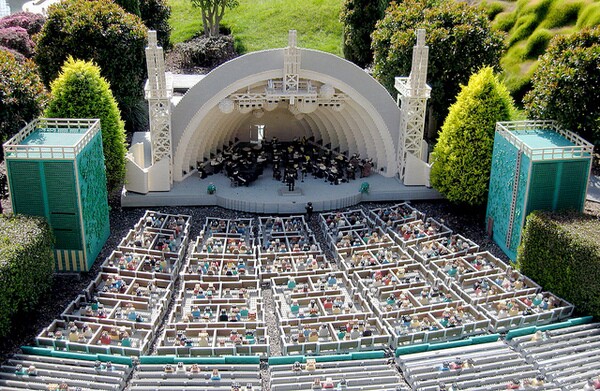

At the Carlsbad theme park, one finds reconstructed American cities like New Orleans, San Francisco, Las Vegas, Los Angeles, and New York. Life-sized Lego incarnations of sleeping elderly beach goers with black socks share space with the Three Pigs of fairytale lore. These kinds of figures and structures enable children to interpret the adult world through Lego styled reconstruction, and adults to refract the real world into a more childlike and perhaps, simple reality.

What about authenticity? In a 1999 article for the journal Pacific Historical Review, Susan Davis argued that authenticity had increasingly become of central importance for tourists. "From the tourists' perspective, the sites they are drawn to must feel real -- they must not seem too carefully managed."5 As result, in the late 1990s and early 2000s, tourism planners focused more on "culture, nature, and heritage as attractions."

Well before Disneyland or Legoland, authenticity was always, to some extent, a factor in and around Los Angeles, even when the authenticity itself remained questionable. Take the influence of white elite Christine Sterling, whose efforts amid a "flowering of Mexican and U.S. relations" and the vanguard of Mexican artists like Diego Rivera and David Alfaro Siqueiros led to the redevelopment of Olvera Street as a romanticized "center of Mexican romance and tourism."6 California historian Kevin Starr summarized the result: "Olvera Street might not be Old California or even authentic Mexico, but it was better than the bulldozer."

Sterling did not stop with Olvera Street. When urban development forced L.A.'s original Chinatown to move, Sterling then created China City in 1937. As with Olvera, Sterling appealed to authenticity through ethnicity; China City trafficked a racialized essentialism, with much of its layout based on sets from the movie "The Good Earth" (based on the novel by Pearl S. Buck).

Ultimately, Sterling's efforts amounted to the following: a white woman reimagining ethnic enclaves in essentialized form for largely middle and upper class white consumers. Olvera Street, argues Miguel Estrada, operated much as Disneyland would 25 years later -- provide a "quaint, colorized, and non-confrontational tourism" for primarily white customers.

Legoland's nostalgia differs markedly, and the park delivers its own version of authenticity. In a region that transformed rapidly and relentlessly in the post war period, a theme park based on the construction-deconstruction-construction possibilities of Legos seems perhaps more authentic than Olvera's Old Mexico. Since Legos remain about individual participation and experience, the construction of literally anything counts as authentic. It simultaneously taps into childhood memories and semiotics while imbuing replicas with an authenticity from the act itself.

The success of Wreck it Ralph can be seen as a testament to renewed Disney efforts in animation and the power of video games in the popular consciousness. Not to be outdone, over the past several years Lego has re-imagined Indiana Jones, Star Wars, Batman, and most recently, Lord of the Rings as video games. While designers imbue these games with humor, they are much like the models one encounters at Legoland: inspired reconstructions. The idea that the video game now incorporates the kind of deconstructed figures one builds out of Legos and also reinterprets the subject material itself into interactive game play, one can see the rise of new forms of nostalgia that connects generations, but in different ways.

Whatever the case may be, Legoland's appeal to nostalgia ties in directly to a Southern California tradition, demonstrating the region's role in reshaping how we remember our history and childhood and just how it manifests in the present.

____________

1 Andrea Adelson , New York Times, "Advertising: Television Spots for Legoland, a New Theme Park", February 18, 1999.

2 John Findley, Magic Lands: Western Cityscapes and American Culture after 1940, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993, 68.

3 Eric Avila, Popular Culture in the Age of White Flight: Fear and Fantash in Subrban Los Angeles, Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2006, 119.

4 Susan Davis, "Landscapes of Imagination: Tourism in Southern California," Pacific Historical Review, Vol 68, No 2, 179.

5 Susan Davis, "Landscapes of Imagination: Tourism in Southern California," Pacific Historical Review, Vol 68, No 2, 187.

6 William D. Estrada, "Los Angeles' Old Plaza and Olvera Street: Imagined and Contested Space" in Western Folklore, Vol. 58, No. 2, Built LA: Folklore and Place in Los Angeles (Winter, 1999,) pgs. 107-129.

Ryan Reft is a doctoral candidate in urban history at the University of California San Diego. His work has appeared in the journals Souls and The Sixties, as well as in the anthology Barack Obama and African American Empowerment: The Rise of Black America's New Leadership. He is co-editor of the blog Tropics of Meta.