From Villa to Pacquiao: Filipino Boxing in L.A. and the Power of a Transnational Punch

In May of this year, Manny Pacquiao and Floyd "Money" Mayweather Jr. battled 12 rounds in what was billed as the "fight of the century." The two fighters carried a long history of antagonism into the ring, though perhaps much of this could be attributed to Mayweather, whose trolling of the Filipino boxer over the years sometimes veered into racism. Pacquiao's loss to Mayweather, a unanimous decision, seems unsurprising in retrospect, especially considering the latter's status as arguably the greatest defensive boxer of his generation. Don't cry for Manny though, an equally lucrative rematch appears very likely down the line. The Las Vegas fight racked in $400 million; when money is to be made, boxing loves to run it back two or three times.

Whatever Pacquiao's future, his 21st century career stands as a testament to the long 20th century legacy of Filipino boxers, whose heyday began in the 1920s and lasted for over two decades; and then again re-emerged mid-century. Francisco "Pancho Villa" Guilledo, a.k.a. "The Living Doll," Diosdado "Speedy Dado" Posadas, and Ceferino Garcia serve as three examples of Filipino boxing champions during this earlier period, while Gabriel "Flash" Elorde, though not a Californian, served as bridge between his predecessor and the luminous Pacquiao. Still, California, especially Los Angeles with its Main Street Gym, Olympic Auditorium, and the Hollywood American Legion Stadium, proved a key locale for the Filipino diaspora and the fighters they supported.

Far from the kind of racial antagonism that has long plagued the Pacquiao-Mayweather relationship, the Los Angeles boxing scene functioned as a multicultural space that included Filipino, Mexican, white ethnic, and black boxers. Main Street Gym provided both competition and collegiality among this diverse stew of fighters, while boxing, for Filipinos laboring across Southern California, served as a source of pride and identity. Filipinos funneled concepts of masculinity through their boxing idols and used these experiences to push back against racism and emasculating notions of sexuality thrust upon them.

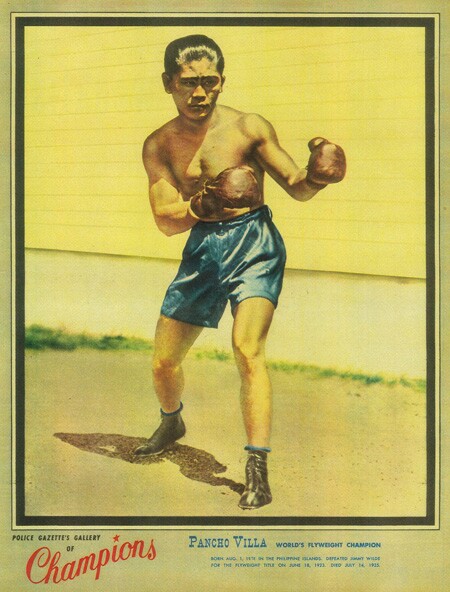

The Pacquiao-Mayweather fight coincides with the 90th anniversary of the Olympic Auditorium's opening, and the July, 1925 death of the renowned Living Doll in San Francisco after a non-title bout in Oakland. A decade and half into the 21st century, 2015 serves as useful moment to consider the history of Filipinos in America's boxing history and L.A.'s role in making it all happen.

Straight outta the Philippines: Villa to Garcia to Pacquiao, 1925 to 2015

"By now, sports fans have heard this so many times -- zero crime, empty roads, a captive nation -- that it can feel tiresome," noted writer Rafe Bartholomew while recounting his experience watching the Pacquiao-Mayweather fight in Metro Manila. "On the ground, however, the quiet that engulfs Manila before Pacquiao performs can feel surreal." Indeed, although it may now seem trite to say, Pacquiao's hold over the nation seems almost godlike. Other journalists, like Ted Lerner, have made similar assertions. "Filipinos love boxing, and the fighters intrinsically know it, which gives the sport a deep meaning and significance." 1

Manny earned his boxing bonafides in the mid 1990s, duking it out at matches in places like Manilla's Mandaluyung City municipal gym with basketball hoops in the background, "faded San Miguel Beer decals on the corner posts, and local government slogans painted on the wall," notes Bartholomew. 2

Ninety years ago this month, Pacquiao's forerunner, Francisco "Pancho Villa" Guilledo, died in San Francisco, ten days after a bout in Oakland. Like Pacquiao, Villa occupied a central place in Filipino hearts, as demonstrated when over 100,000 crowded the streets of Manila for his funeral. He too would rise from poverty in the Philippines by fighting his way out of the teeming Philippine capital. 3 Moreover, his exploits, flyweight Championships in 1923, 1924, and 1925, inspired others. "[T]he new champion impressed the large crowd with his victory," wrote the New York Times after Villa's 1922 championship bout in Brooklyn's Ebbets Field. "Popular in the extreme prior to the battle, Villa added many new admirers to his legion of friends through the workmanlike manner in which he attained the title. The Oriental Champion was the master throughout." 4 While many of his victories would come on the East Coast, his successors would help shift the action in the West.

With the opening of the 10,000 seat Olympic Auditorium in 1925, and a growing Filipino population employed in the homes of Anglos as domestic workers and laboring in the fields of San Fernando and San Gabriel Valleys, Los Angeles -- and California more generally -- would become a center of the multicultural boxing world. 5

The first significant wave of Filipino migration came in 1923, when over 2,000 arrived in California. 6 Ten years later, over 6,000 resided in Los Angeles, most living in the downtown neighborhood known as Little Manila, the community bordered by San Pedro Street to the east, Sixth Street to the south, Figueroa Street to the west, and Sunset Boulevard to the North. Twelve restaurants, seven barbershops, the immigrant newspaper The Philippines Review, and the Manila Portrait Studio all helped to buoy the Los Angeles Filipino diaspora. 7

While gambling and taxi dancehalls provided the overwhelmingly male Filipino community with distraction from their grinding labor, these activities drew condemnation from some quarters within Little Manila. Boxing, however, drew no such criticism; moreover, it brought a diverse population -- sometimes divided ethnically between Ilocanos, Visayans, Tagalogs, and Boholanos -- together into one experience. "They didn't care if a person was Visayan, Ilocano, Boholano, Cebuano," notes Stockton's Jerry Paular. When a Filipino boxer emerged victorious, "Ilacano was embracing the Visayan and the Tagalog." 8 In Los Angeles, Johnny Samson, one of only two Filipino boxing trainers at the time, served as chairman of the L.A. Filipino Unity Council. 9 Boxing would prove to be one of the most influential and lasting forms of popular attraction among Filipinos in California.

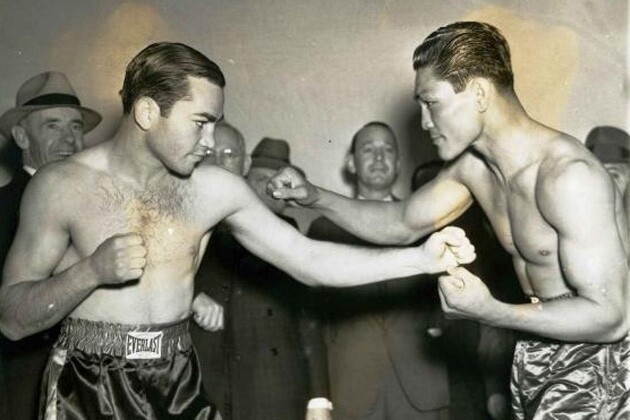

Following Villa's death, other Filipino boxers showed flashes of brilliance. For example, in 1931, Diosdado "Speedy Dado" Posadas emerged as Villa's possible successor, defeating Jewish boxer David "Newsboy Brown" Montrose at the Olympic Auditorium, leading Ring magazine to declare "Little Dado" the finest "Filipino fighter seen in this country since the days of Villa." 10

Dado's exploits inspired African American boxer "Hurricane" Henry Armstrong to move to California. "Why, Dado was drawing super-gates that netted him as much as $5,000 every two weeks," Armstrong wrote in his autobiography. "And on the ceiling over [my] staring eyes appeared a vision of Speedy Dado, just as he'd looked on the cover of the recent issue of Knockout ... smiling dressed in elegant, expensive clothes. A large diamond ring flashed insistently on his hand." 11 Armstrong soon moved from East St. Louis, Illinois, to Los Angeles, trained regularly at Main Street Gym, and would go on to become the only boxer to retain three championships concurrently. 12

Yet, argues historian Linda Espana-Maram, it would be the California based Filipino fighter, Ceferino Garcia, known as the "Bolo Puncher", who would inherit Villa's legacy and capture the hearts of Filipinos andFilipino Americans. Garcia holds the most victories ever by a Filipino boxer, pioneered the "bolo punch," and remains the only boxer from the Philippines to ever win the middleweight crown. In 1989, he was elected to the World Boxing Hall of Fame, and though he died in San Diego in 1981, he is buried at Valhalla Memorial Park Cemetery in North Hollywood.

Garcia plied his craft patiently throughout the 1930s. The "Bolo" puncher lost more than a few fights -- over two dozen -- but demonstrated gradual improvement throughout the decade, much as Pacquiao would decades later in his own rise to prominence. Though Garcia lost his first attempt at the World Welterweight Championship to Barney Ross by decision, Bill Henry, Los Angeles Times sports editor, argued it was Garcia who emerged victorious: "the hero ... was Ceferino Garcia of California ... [who] wore the carmine badge of courage and the stole the show. [Garcia] forced a highly partisan audience to forget their prejudice in appreciation of the Filipino's courageous comeback." 13

For Filipino laborers, Garcia's transformation from immigrant to champion mirrored their own aspirations and journeys, exemplifying "themes of heroic quests, validation, and metamorphosis" similar to the heroes of Filipino folk epics such as Agyu, Lam-ang, Banna, and Labaw Donggon, notes Espana-Maram.

"Ceferino was always there. There was a time when close to 50 armed men swooped down on him, gangland fashion and you know what, he came out of it unscathed and triumphant," one popular story recounts. Filipino laborers told "hero narratives" of Garcia besting 50 armed men in part as a means to displace their own struggles as unemployed whites physically attacked them as revenge for allegedly lowering wages and worsening work conditions. Employers too sometimes targeted Filipino workers for violence when they organized unions or went on strike.

Garcia's physical size challenged stereotypes of Filipinos "as small agricultural workers" fit only "for the short hoe or meek domestics and service workers." Hard and tenacious, Garcia embodied the resiliency and "potency" of his countrymen, eventually achieving his destiny as world champion. "Filipino workers," through these narratives, writes Espana-Maram, "codified their ideals of Filipino masculinity: Garcia, outnumbered fifty to one, relying only on his wits and raw muscle, fought undaunted, and emerged victorious." 14

Imperial Dreams and Fighting Realities

That boxing served as a source of pride and identity and a means with which to challenge dominant racial and sexual narratives regarding Filipinos in America rests on a central irony: the sport had been introduced by American servicemen during the U.S. occupation of the archipelago. According to sports historian Janice Beran, Filipinos first encountered the sport alongside a U.S. drill ground where in the bandstand, Oregon servicemen held a boxing exhibition. The sport soon "aroused widespread interest and remarkable participation," Beran writes. 15 In its early years in the Philippines, the servicemen boxing consisted of white and black fighters, hinting at the sports multiracial promise. Though the armed forces remained segregated, "the all-black 9th and 10th U.S. Cavalry, 24th and 25th U.S. Infantry, and 48th and 49th U.S. Volunteer Infantry formed a significant percentage of the American soldiers serving in the Philippines between 1899 and 1902," notes sport scholar, Joseph Svinth. 16

U.S. imperialism had long sought to encourage "democratic values and Protestant Christianity." American officials in the Philippines did this primarily through a two-prong approach: education and sports. Speaking to Methodist leaders in 1899, President William McKinley asserted "We could not leave them to themselves ... there was nothing left for us to do but to take them all, and to educate them, and to uplift and civilize and Christianize them ..." 17 Obviously, such proclamations came with more than a dose of Kiplingesque "white man's burden." In the Philippines, schools and Christian organizations like the YMCA promoted it along with other sports like baseball and basketball, as a tool for imposing U.S. ideals while also eliminating activities that officials saw as degenerative such as gambling and cock fighting. 18

Still, if U.S. officials hoped boxing and other sports wound function in a unidirectional manner, they would be disappointed as Filipinos soon used athletics as a tool to challenge conceptions of Western superiority. Additionally, for much of the first half of the 20th century, the U.S. heavily restricted Asian immigration; Filipinos proved the exception to the rule. Until the passage of the Tydings-McDuffie Act in 1934, due to their status as U.S. nationals, Filipinos were able to migrate to America while other Asian peoples could not.

U.S. prohibitions regarding Asian immigration also made the arrival of Filipinos on U.S. shores more likely as a much needed labor source. An expanding Los Angeles would be a prime destination as its economy boomed during both WWI and WWII. Still, like other Asian immigrants, U.S. policies prevented them from voting, holding land, purchasing homes, or applying for citizenship. 19 In the face of such discrimination, boxing served as means to suture Filipino identity, masculinity, and sexuality, while also creating a sense of community and belonging.

Boxing and Los Angeles Filipino Diaspora

Tuesday night was fight night, and for Angeleno Filipinos it provided a respite from working in the fields around the city or as domestics in the homes of L.A.'s white population. "On those nights," remembered Toribio Castillo, "even washing dishes for ten hours didn't matter. We went." The bigger the fighter the greater the anticipation: "When the big boys [champions] are in town, you can't even see the end of the ticket line." 20

Southern California's car culture enabled impoverished laborers to travel long distances at minimal cost to support their favorite fighters and express ethnic solidarity. Though Filipinos turned out for countless numbers of their own fighters, Garcia especially drew plaudits. "Garcia! You know, that [was] all we Filipinos had," noted Antonio Cabanag, a worker at Pasadena's Thrifty Drug Store who attended every Garcia match in Los Angeles during the 1930s. Likewise, Filipino fans filled stadiums across the state, such as L.A.'s Olympic Auditorium, San Francisco's Dreamland Arena, and Stockton's Civic Arena. 21 In Stockton, matches brought out men, women, and children, notes writer Dawn Bohulano Mabalon. 22

Boxing, after all, enabled Filipinos to strike a white man with his fists "and not get arrested," noted Filipino American writer Peter Bacho. The ring "suspended society's norms those rules that embodied a racial and social order favoring color over ability, class over potential," he wrote. 23 With this in mind, it should come as no surprise that as one promoter noted at the time, "Filipinos versus white fighters" remained the favorite among fans. "Knocking out a white fighter challenged ideologies of white supremacy," points out Bohulano Mabalon. Still, Filipino audiences viewed victories against other ethnic groups in similar terms, adding greater complexity and perhaps conflict to the meaning of the sport. For example, a victory against a Mexican boxer represented "the crushing of Mexican labor competition." 24

As consumers, Filipinos also exerted their power in the audience. When white spectators taunted Filipinos boxers and fight goers with racial epithets in areas likes Watsonville, CA, Filipino fans resorted to boycotting boxing matches in such places. As spectators, they could express equal parts exuberance and anger; emotions that as workers might get them reprimanded. Sometimes, events in the ring led to emotional outbursts from the crowd that could turn violent, as happened in a 1932 boxing match in Pismo Beach. When the referee stopped a fight between Henry Armstrong and Filipino Kid Moro, the crowd, believing the decision unfair, went wild and stormed the ring. Still, Armstrong and Moro fought well-attended rematches in Stockton and Watsonville, each ending in a draw. 25

Yet, although boxing provided a means for community and asserting equality, white journalists, even when in admiration, often depicted fighters in racial terms. Villa endured descriptions like "Simian demon"; the L.A. Times described Garcia as a "bronzed Oriole." When the half Chinese boxer Tony Mar fought Filipino Jimmy Florita in 1943, the Times noted that no two peoples had suffered at the hands of the "Japs," more than the Chinese and Filipinos and that "these fighting little tan tigers" promised to "attract a packed house." 26

Sexuality sometimes proved an issue. Villa's habit of consorting with white women, like that of the famous black boxer Jack Johnson, scandalized Americans and fed stereotypes regarding the seductive and corrupting powers of Filipino men. Indeed, in some moments, dominant culture depicted Filipinos as emasculated, feminized domestic workers, and in others as seductive lotharios bent on impregnating white women. "[T]he worst part of his [the Filipino] being here is his mixing with you white girls from thirteen to seventeen," argued the nativist Judge D. W. Roherback of Watsonville, CA, "keeping them out till all hours of the night. And some of these girls are carrying a Filipino baby inside of them." 27

The 1950s to Today

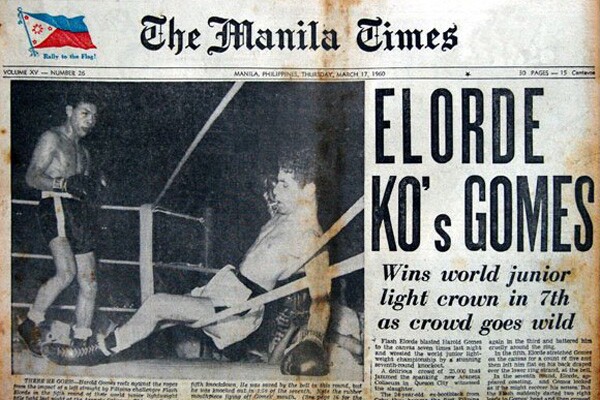

After Garcia, another iconic Filipino did not emerge until the 1950s when Gabriel "Flash" Elorde, like Villa before and Pacquiao after, "galvanized the nation and carried boxing to greater heights than ever before," according to boxing journalist, Nigel Collins. Elorde ushered a second golden age of Filipino boxing, cementing his place among the greats with a 1960 victory at Araneta Coliseum in Quezon City, Philippines, in front of 36,000 fans; this is the same stadium that served as the setting for the classic Ali-Frazier "Thrilla in Manila" battle. Capturing the Junior Lightweight championship and holding it for seven years, Elorde transformed into a national icon "as renowned for his impeccable personal life as much as his fighting prowess," notes Collins. 28

Described as "modest" and "munificent", Elorde frequently befriended opponents, even inviting them into his home for post match dinners. Though he died thirty years ago of lung cancer, Filipino children continue to learn of his "accomplishments in and out of the ring" in schools across the Philippines. Though more than a few title holders emerged in between Elorde's retirement and Pacquiao's accension -- Erbito Salavarria, Ben Villaflor, Rolandao Navarrette, Dodie Boy, and Gerry Penalosa to name a few -- Villa, Garcia, Elorde, and Pacquiao serve as through line for Filipinos around the globe and especially in California. 29

Over the years, Pacquiao has more than cemented his ties with Los Angeles through frequent visits to Bahay Kubo and May Flower Seafood restaurants, in Filipinotown and Chinatown respectively; appearances on the Jimmy Kimmel Show (whose namesake of course famously appeared in the fighter's entourage at the Las Vegas bout); and training at Wild Card gym in Hollywood.

For L.A.'s Filipino American residents, Pacquiao's status ranks as more than just a boxer. "For the Filipino community in Echo Park, this is not just a gathering but a moment to witness for our people," Jason Yap told the Los Angeles Times in May. 30 However, he represents the culmination of numerous overlapping processes, ranging from imperialism and immigration, to identity formation and community solidarity. Long before Pacquiao emerged as one of his generations' greatest fighters, his Filipino predecessors occupied similar places in the hearts of their diaspora. Like Elorde, how Pacquiao carries himself matters too. Mayweather might be the better fighter, admitted Angeleno Joycelyn Geaga-Rosenthall, "But I like Manny better. He has a better spirit and I can support a good man." 31

Whether or not, a Pacquiao-Mayweather rematch takes place, rest assured, Los Angeles, Filipinos and Filipinos Americans have long been a central player in the nation's boxing milieu.

_____

1 Nigel Collins, "The heartbeat of an entire nation," ESPN.go.com, April 10, 2013

2 Rafe Bartholomew, "Mayweather Pacquiao: A Sad Morning in Manila," Grantland, May 4, 2015

3 Linda Espana-Maram, Creating Filipino Masculinity in Los Angeles's Little Manila: Working Class Filipinos and Popular Culture, 1920s-1950s, (New York: Columbia University Press, 2006), 76.

4 Ibid., 76.

5 Gerald Gems, "Sports, Colonialism, and U.S. Imperialism," Journal of Sport History, 33.1 (Spring 2006): pg. 11; Espana-Maram, Creating Filipino Masculinity in Los Angeles's Little Manila.

6 Espana-Maram, Creating Filipino Masculinity in Los Angeles's Little Manila, 4.

7 Ibid., 5-6.

8 Dawn Bohulano Mabalon, Little Manila is in the Heart: The Making of a Filipino/a American, (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2013), 120.

9 Espana-Maram, Creating Filipino Masculinity in Los Angeles's Little Manila, 86.

10 Ibid., 77.

11 Ibid., 99.

12 Ibid., 87.

13 Ibid., 78.

14 Ibid., 81.

15 Janice A. Beran, "Americans in the Philippines: Imperialism or Progress through Sport?" The International Journal of the History of Sport, 6:1, 62-87, DOI: 10.1080/09523368908713678.

16 Joseph Svinth, "The Origins of Philippines Boxing," The Journal of Combative Sports, July 2001

17 Beran, "Americans in the Philippines," 63.

18 Ibid., 8, 11.

19 Espana-Maram, Creating Filipino Masculinity in Los Angeles's Little Manila, 4.

20 Ibid., 79.

21 Ibid., 80.

22 Bohulano Mabalon, Little Manila is in the Heart, 128.

23 Ibid., 128.

24 Ibid., 127.

25 Espana-Maram, Creating Filipino Masculinity in Los Angeles's Little Manila, 100.

26 Gems, "Sports, Colonialism, and U.S. Imperialism," 11; "Ceferino Garcia Meets Negro Nemesis in Olympic Feature Tonight," Los Angeles Times, June 9, 2015, A11; "Chinese and Filipino Do Bit for Countrymen," Los Angeles Times, July 16, 1943 A12.

27 Espana-Maram, Creating Masculinity in Los Angeles' Little Manila, 111, 120; Mai Ngai, Impossible Subjects: Illegal Aliens and the Making of Modern America, (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2003).

28 Nigel Collins, "The heartbeat of an entire nation," ESPN.go.com, April 10, 2013

29 Nigel Collins, "The heartbeat of an entire nation," ESPN.go.com, April 10, 2013, http://espn.go.com/boxing/story/_/id/9155189/history-defines-love-affair-boxing-philippines

30 Ahn Do, Jerome Campbell, and Christopher Goffard, "Mayweather vs. Pacquiao: L.A. fans pull for local hero with 'good heart'," Los Angeles Times, May 2, 2015, .

31 Ibid.