L.A.'s Under-the-Radar City Attorney Race: A Look at the Money

This article is published in conjunction with Crosstown.

The job of City Attorney is the second-highest elected office in Los Angeles. Yet as election day approaches, the race to succeed termed-out Mike Feuer is generating little attention. It has been overshadowed by the mayoral match-up, some bitter city council contests and even a battle to be the next city controller.

In the June primary, progressive candidate Faisal Gill finished first in a seven-person field, though with just 24.2% of the vote. Squeaking into the runoff to meet him was Hydee Feldstein Soto, who received 19.9%. Election day is Nov. 8.

The city attorney has a sprawling set of duties: The office writes legislation, defends the city in lawsuits, can pursue legal claims and prosecutes misdemeanors. The position requires not just legal but high-level managerial skills — the office employs more than 500 attorneys.

In the primary, Gill had $1.5 million at his disposal, according to disclosure statements filed with the City Ethics Commission. That included nearly $1.2 million in personal loans, the largest self-funding effort in the city outside mayoral contender Rick Caruso. In the first round Feldstein Soto raised $393,000 in traditional donations, where the maximum individual contribution allowed is $1,500. She augmented that with a $50,000 personal loan, and $267,000 in city matching funds (given to candidates who raise a certain amount in small donations from local residents).

The disparity continues in the runoff. Through Sept. 24 (the most recent campaign finance deadline), Gill reported contributions of $569,000, including another $400,000 in personal funds. Feldstein Soto has built a war chest of $335,250, including $75,000 in personal loans.

Here is more on how their money breaks down in the runoff period.

Faisal Gill

Gill works as a civil rights attorney. A former Republican now registered as a Democrat, he lost races for elected office in Vermont and Virginia. The current Porter Ranch resident became a candidate for City Attorney after representing a Black man who filed a racial profiling lawsuit against the city.

Of the $2.1 million Gill has secured since entering the contest, nearly $1.6 million is his own money.

In the first filing period of the runoff, he generated 177 donations, according to Ethics Commission disclosures (new totals will be revealed this week). That compares with 497 donations secured by Feldstein Soto.

In the runoff period through Sept. 24, Gill has raised about $170,000 in traditional donations. Approximately $62,000 of this emanated from outside the state, and some of his top donor ZIP codes are in Virginia and Texas, according to a City Ethics Commission dashboard of financial data. An estimated 36.5% of his donations are from outside California.

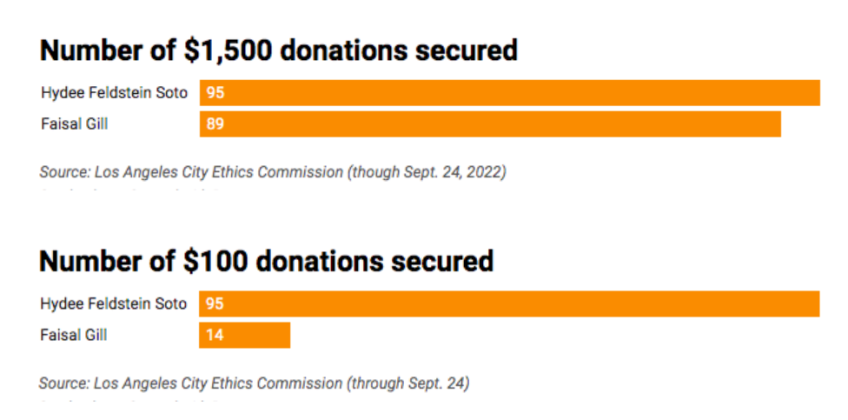

An analysis of publicly available campaign data shows that Gill has received 89 maximum donations of $1,500, with another 18 contributions of $1,000. Only about 26 donations were for $200 or less.

At least 18 of Gill's donors work in the legal field, according to Ethics Commission disclosures. Another 15 are physicians.

Eleven of those physicians have provided maximum donations. Others who topped out include five people listed as CEOs, three managers with the business Woodland Hills Fireplace Barbecue and the campaign committee for Assemblyman Isaac Bryan.

Hydee Feldstein Soto

Like Gill, finance law attorney Feldstein Soto has never held public office. She was born in San Juan, Puerto Rico and has lived in Los Angeles for nearly 40 years. She resides in Mid-City.

Feldstein Soto relies more on small donations than does Gill. She has 70 donations of $214. The city's 6:1 matching funds program, an effort to level the playing field, means each donation of this amount can spur another $1,284. The original donation and the match together total $1,498, or nearly the maximum contribution of $1,500. (Gill's personal contributions make him ineligible for matching funds).

Feldstein Soto has also pulled in 95 donations of $1,500 and 20 of $1,000.

According to Ethics Commission filings, in the runoff period she received 95 donations of $100. That compares with 14 for Gill.

At least 70% of the money Feldstein Soto raised from donors in the runoff period comes from inside California. Only about $17,350 is identified as from outside the state.

Not surprisingly given her background and the seat she is running for, Feldstein Soto has extensive support from those in the legal field. This includes more than 70 donations from attorneys.

She also has more than two dozen contributions from people in the real estate development sector. Seventeen people whose job title is "consultant" have given her money.

Two dozen lawyers have given Feldstein Soto the top donation amount of $1,500. She also received maximum contributions from the unions representing city of Los Angeles firefighters and Department of Water and Power employees, as well as a Planned Parenthood of L.A. County political action committee. Another $1,500 came from someone identified only as "Iris."

How we did it: We examined publicly available campaign finance data from the Los Angeles City Ethics Commission in the period up to Sept. 24, 2022. Some of the data on an Ethics Commission dashboard may be updated and not fully reflected in this article. More information about our data is here.