How Green Are Our Presidents?

Although a substantial majority of Americans believe that environmental issues -- clear air and water, a healthy land and people -- are among their highest priorities, that's not always how they vote.

Politicians, incumbent and hopeful, have taken due note and give lip-service to our need better to protect our place in this place; once in power they tend to ignore legislating on those matters that on the campaign trail they had assured the electorate were of heart-felt concern.

Even those outright hostile to a greener sensibility tend not to pay for their studied disregard of the public's putative desires to be green.

Presidents are as complicit in this conundrum as any other elected official. Argues Brian Clark Howard on The Daily Green: "In many ways, being green has never been easier, especially for politicians. The vast majority of Americans now say environmental protection is important to them, and few would vote for a leader who explicitly claims to be 'anti-environment.'" Yet it is also true that "America's highest office has long had a relationship to the planet that is anything but straightforward."

That's as true of the first generation of chief executives as has been for President Obama (and also would hold true for a possible Mitt Romney presidency).

In a seriously playful attempt to sort out which presidents more fully have aligned themselves with their era's environmental awareness, The Daily Green's Howard has selected the ten most environment-friendly presidents in the nation's history (and in another listing he tabulates the worst; that one is a bit more fun!).

While Howard admits that any such list must be subjective, he frames his exercise around whether his subjects worked to advance the "evolution of environmental policy and protection"; his is a reasonable ranking of those "administrations with the best environmental legacies."

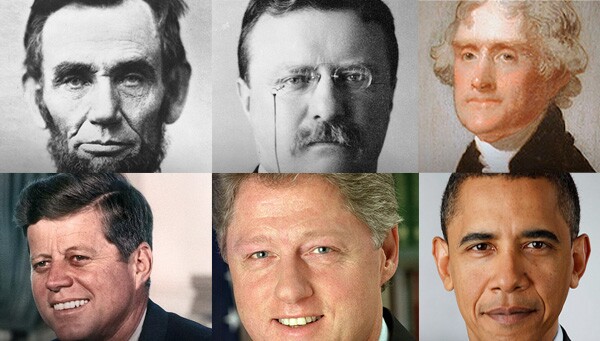

It is no surprise then that topping the list was our 26th president, Theodore Roosevelt -- his robust commitment to the creation of national forests, monuments, parks, and refuges far exceeds that of any other chief executive, living or dead.

Coming in second, also not unexpectedly, is that engineer-cum-president, Jimmy Carter. In a single term, he designated millions of acres in Alaska as wilderness, signed landmark legislation that required stricter regulation for clean water and air, and for the mitigation of toxic superfund sites; his establishment of the Department of Energy was a bold move amid a global energy crisis.

Bringing up the next cohort are Jefferson (think yeoman farmers, Lewis and Clark, and the Louisiana Purchase); Clinton (a stretch, I think, despite his signing off on a series of Antiquities Act-protections for such rugged terrain as Escalante-Grand Staircase National Monument).

As for Richard Nixon, Howard dubs him the "Reluctant Environmentalist." He scores high for the EPA's creation and fails for such poisonous wartime policies as the use of Agent Orange to defoliate Vietnam. That's why Nixon is the only cross-over president, cited also as one of the most anti-enviros to occupy the White House.

The sixth-ranked FDR should have been moved ahead of Clinton and Nixon, given Interior Secretary Harold Ickes' energetic expansion of the Park Service's domain; and the restorative work of the Civilian Conservation Corps.

Next up, Abraham Lincoln. He's credited with launching the National Academy of Sciences and the Department of Agriculture; a bonus was the provision that gave Yosemite and the Mariposa Grove of Big Trees to the state of California: "upon the express conditions that the premises shall be held for public use, resort and recreation." When the state failed to live up to the letter of this law, and the federal government took the fabled terrain back.

LBJ claims the eighth spot (notably for the 1964 Wilderness Act, and a host of other environmental protections); Woodrow Wilson comes in ninth (The National Park Service was founded on his watch); and weighing in at tenth is JFK.

This latter choice gives pause. Now, almost 50 years after his assassination, may be a good time to reflect on his environmental accomplishments. How verdant was Camelot?

Daily Green offers little support for Kennedy's selection -- yes, the 35th president may have been influenced by Rachel Carson's "Silent Spring," and certainly his staff was able to persuade him convene a blue-ribbon Science Advisory Committee to investigate the bestseller's central arguments about the impact of DDT and other pesticides on all life forms. It largely concurred with the embattled Carson's conclusions, giving her work a presidential imprimatur.

Otherwise, Kennedy's environmental record appears slim. His work in the House of Representatives and Senate shows little passion for conservation measures, although he was a staunch advocate of the Cape Cod National Seashore, his backyard playground.

Once in the White House, this pattern continued. He signed the legislation that protected Cape Cod's shoreline, as well as the Gulf's Padre Island, and Pt. Reyes on California's northern coast; hosted a Conservation Conference at the White House (the first in half a century); and promised to sign the Wilderness Act if Congress approved it. Still, he was also very, very careful not to offend the easily offended and all-powerful chair of the House Committee on the Interior, Rep. Wayne Aspinall.

When given the opportunity to make his mark, note how small were this president's gestures: in May 1961, for instance, Kennedy used the Antiquities Act to set aside 310 acres for Alabama's Russell Cave National Monument. He used it again when Congress was in recess in late December, 1961 to establish Buck Island Reef National Monument, covering 850 watery acres in the Virgin Islands. And in May 1963 he actually decreased the size of Bandelier National Monument.

Of his boss' failure to engage fully on conservation matters, Secretary of the Interior Stewart Udall lamented: "He lacks the conservation-preservation insights of FDR & TR, and it will take some work to sharpen his thinking & interest."

No Teddy, Jack was also no Ron; I'd take Udall over Reagan's Interior Secretary James Wattany old day. Kennedy's administration was also a far cry from the nefarious standard set by the Teapot Dome -- besmirched presidency of Warren G. Harding.

However limited Kennedy's environmental commitments may have seemed, they also bore no resemblance whatsoever to the aggressively anti-green legislation and rhetoric that defined George W. Bush's presidency. Little wonder that The Daily Green flags Bush as the "Worst Environmental President in History."

Of those who have succeeded him in the White House, Kennedy reminds me most of our current chief executive, Barak Obama.

Like his charismatic predecessor, Obama is an urban (and urbane) soul, more comfortable dressed up than down; he is smart and cautious, tentative and tenacious. And while he understands the value of a strong environmental agenda, as did Kennedy, Obama's perception of the political constraints he faces has allowed him to set aside its demands so as to focus on issues that seem more immediate, winnable, safe.

Whether that strategy would have brought Kennedy a second term we have no way of knowing; or to know whether reelection would have freed to tap into his inner environmentalist (should it have existed).

Similarly, if President Obama wins this November will he suddenly get down to earth, emerging as the second coming of Theodore Roosevelt?

There is this hope: Roosevelt was not nearly as forceful a conservationist during his first term as he became during his second. And while not every President can (or should) be a Rough Rider, that fact doesn't lessen contemporary environmentalists' hunger for a forceful, take-charge leader.

Someone whose force of personality and strength of conviction might compel us finally to act on those green ideals we profess to uphold.

Char Miller is the Director and W.M. Keck Professor of Environmental Analysis at Pomona College, author of "Public Lands, Public Debates: A Century of Controversy" (Oregon State University Press), and editor of "Cities and Nature in the American West." He comments every week on environmental issues. Read more of his columns here