Oil and Water Don't Mix: What Fracking is Doing to South Texas

"You can't believe the flood of money that's pouring into San Antonio!"

That's Steve talking, a close friend and an accountant with his finger on the financial pulse of the nation's seventh largest city. At a time when many other communities are struggling to make ends meet, the Alamo City seems flush.

The source of this new pelf lies a couple of hours to its south, down I-35 and US 281, deep in the brush country of south Texas. To be more precise, its origins lie thousands of feet below the rolling coastal plain, in the gas-and-oil deposits locked in the Eagle Ford Shale formation; this seam runs beneath more than 20 counties that stretch from the Rio Grande Valley north and east into central Texas.

To tap those resources, major energy companies (and smaller ones, too), are offering upwards of seven-figures for an annual lease, eye-popping dollars for hardscrabble ranchers who in the past have had to take a second or third job just to hold on to their lands, let alone maintain their livestock operations. To that kind of payday, Steve observed, "not many are saying no."

Ditto for those just seeking a steady paycheck: roughnecks have swelled the population of a town like Alice; or Cotulla, Dilley, Yorktown and Cuero. Once quiet Farm-to-Market roads are jammed with fast-moving drilling rigs, pipe-carrying flatbeds, tankers and shiny pickups. Motels and diners are overwhelmed with business, too, economic activity that has put a lot of money on a lot of tables.

Map courtesy Railroad Commission of Texas

Even in distant San Antonio, which has become the play's service hub for finance, information technology, infrastructure and transportation. Steve laughed: "Just try renting a truck in town - you can't do it."

This being dusty south Texas, there is a lot of grit beneath that glitter. Used to booms and busts, everyone is waiting for this bubble to pop - and it will. When it does it will have predictable impact on now-inflated prices for food, clothing and lodging; the sidewalks and streets will empty out - lots of sorrow after a burst of short-term material gain. Here's hoping that county governments and tax-dependent school districts, currently reveling in their good fortune, have put some of it into rainy-day funds.

More devastating, because they'll be more enduring, are the environmental losses that are already putting the region on edge. The Eagle Ford fossil-fuel strike, like so many around the world, is driven by the hydraulic-fracturing technologies. To capture oil and gas buried so far underground, and trapped in dense shale, energy companies are wielding this new tool to blast under high-pressure millions of gallons of water, tons of sand, and a toxic cocktail of chemicals, thereby fracturing the rock and releasing trapped reserves of oil and natural gas; these molecules are then captured and pumped to the surface.

This dynamic system is earning record profits for energy companies like ConocoPhillips and Chesapeake Energy, and service-giant Halliburton, and there is financial trickle down for the localities in which fracking occurs. In 2010, according to a recent report, Eagle Ford has generated an estimated $3 billion in revenue for producers and local governments.

But there is an immediate cost to that gain, as south Texans are beginning to realize: In a region that does not get a lot of precipitation, and whose rivers are more dry than wet, the extensive pumping of local aquifers to be injected into the thousands of hydro-fracking wells are or will soon dot the arid landscape is creating a problem for generations to come.

It is not simply that a single, high-volume injection well can use astonishing amounts of water; or that this sudden rate of pumping - multiplied by the thousands - will be almost impossible to replace given how little rain sweeps over this flat, sandy terrain. Added to these dilemmas is another: This extracted water is laced with chemicals, a toxicity that is difficult to wash out; in some cases disposed of as if it was hazardous waste. Once it's gone, it is gone.

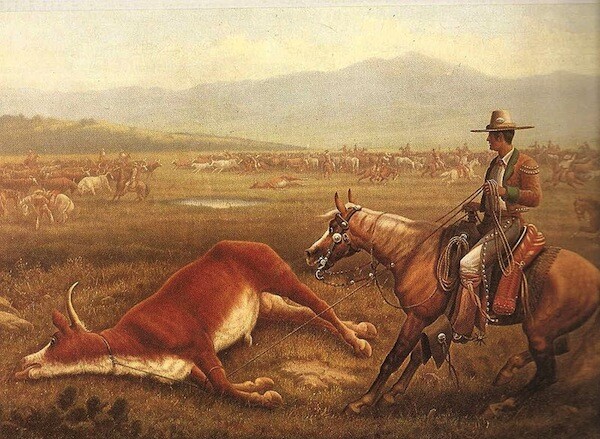

The Spanish would have been stunned by this casual destruction of this essential life-sustaining resource. When its first explorers pushed north out of Mexico to expand its imperial boundaries, they marveled at what one of them called a "fine country with broad plains - the finest in New Spain." Yet as rich as these grasslands were, the Spanish were not fooled into thinking this was a well-watered environment.

Recognizing, in the words of Texas State University historian Frank de la Teja, that "land was plentiful, water was not," they constructed a legal regime across northern Mexico and what would become southern Texas that compelled human habitation to adapt to this environmental constraint. Because this "countryside is deserted and sterile," argued military engineer Agustin de la Camara Alta, because it had negligible surface water, "which is only available in the Rio Bravo [Grande] and Nueces River and a few small watering holes," the territory was "worthless except for raising cattle."

Aridity in turn shaped land-owning patterns: For grazing to be successful, Spanish, and later Mexican, officials understood, large acreage was essential. "Richard King and the cattle barons who followed recognized the suitability of many of the adaptations made by rancheros and vaqueros," writes de la Teja, particularly the definitive power of limited water, making it "the central theme in regional development."

Nothing has changed since then, argues Hugh Fitzsimmons. A fifth generation rancher in south Texas, and a good friend from when I lived in San Antonio, his family's spread covers roughly 20-square miles insuring since the mid-nineteenth century that its livestock has had decent access to water. He's rightly worried, though, that fracking will destroy the fragile balance that his ancestors were able to maintain on this rough ground.

Start with the rapid pumping out of the Carrizo Aquifer, and then couple that with a multi-year, crippling drought: Are south Texas' ranching days numbered? That's what's worrying Hugh, and led him to push back politically. "I have tried to marshal support for limiting the amount of water that can be extracted from the Carrizo," he wrote me recently, but with little success. "Money is being thrown around like there is no tomorrow, which there certainly will not be if this keeps up."

Yet the local agency charged with regulating water resources so far has failed to uphold its mission: "our ground water conservation district is so backward that they are still focusing on rain enhancement through cloud seeding. Last month I hired a hydrologist to come down and do a presentation that I hoped would lead to a one-day public workshop/symposium. The board turned it down because they said they did not want to spend taxpayer money on something that no one would attend."

Local governments across the country have exhibited the same puzzling resistance to protect the public's health and welfare, from California and Colorado to Pennsylvania and West Virginia; our future water supplies may have a limited future, a hidden cost we are only beginning to appreciate.

At the Dirty Energy Week strategy conference in Durban, South Africa | Photo: Friends of the Earth International/Flickr/Creative Commons License

This pattern is being replicated overseas, too. Ranchers in South Africa, for example, have been confounded by their elected officials' unwillingness to defend local water resources and thus the livelihoods of those who for a century or more have worked the nation's arid central region known as Karoo (which means, appropriately enough, "thirsty land"). Shell and other global energy corporations anticipate drilling thousands of hydraulic-fracking wells in the coming years, which may well serve as a death knell to the small communities that dot this flatland. Should Shell's exploratory wells come up empty, or prove unprofitable, there will be some relieved folks in the South African outback.

South Texas' resources are already in full development, so its need for relief is more pressing. There are several small, hopeful signs. On February 1, a new law takes effect in Texas: Frackers will be required to identify the specific chemicals used in their injection processes, and they will also have to disclose the exact amount of water they pump. As reported in the New York Times, the Texas Independent Producers and Royalty Owners Association indicates that fracking wells may use upwards of five million gallons over a three-to-five day span; and at that rate by 2020 the state's rural counties will be water-stressed. A new website will monitor this new data - fracfocus.org - and if successful it might alter Texas' deplorable reputation for holding energy companies accountable. For up until now, says Mark A. Engle, a USGS geologist, Texas has ranked "pretty much dead last of any state I've worked with for keeping track of that sort of data."

Another potential bright spot is the use of Liquid Petroleum Gas (LPG) as a substitute for water as a fracking agent. "My understanding is that there is no danger of cross contamination with LPG and that the recoverability is enhanced also," Fitzsimmons notes, and then pauses: "the downside is that it is like having an atom bomb in your backyard."

OK, water is less volatile. How ironic then that the celerity with which energy companies are sucking up it up may detonate the Eagle Ford play prematurely. So worried are wellfield producers that they might run out of water before they have extracted every ounce of oil and gas from this formation that at least one of them has approached the San Antonio Water System to secure more than 6000 acre-feet of recycled water a year; and has agreed to pay all costs associated with transferring this flow to the production sites, netting the water purveyor a tidy annual profit of two million dollars.

If this arrangement comes to pass, it will be yet one more example of how San Antonio will make bank out of the South Texas boom.

Char Miller is the Director and W.M. Keck Professor of Environmental Analysis at Pomona College, and editor of the just-published "Cities and Nature in the American West." He comments every week on environmental issues.