Taking the Long View: California's Environment in 2064

As KCET begins to celebrate its 50th Anniversary, we're engaging the public in a series of conversations, starting with "How do you envision a better state?" Contributor Chris Clarke shares his ideas below. Share yours here.

When you write about the environment for a living, you pretty much write about bad news. It's not that there aren't positive things to report in the environmental field: it's just that they tend to be tiny, tentative attempts to undo the massive damage we've done to the planet's other inhabitants, its living systems. The bad news is generally larger, and more often than not, irreversible.

So when I was offered a chance to write about the California I'd like to see in 50 years, it took a moment to sink in. Writing about what I want, rather than about what I don't want? That was going to exercise mental muscles long grown flabby from disuse.

I don't think I'm the only one who's fallen out of the habit of expecting good times ahead. It's hard to imagine a utopian future for California when the state faces some of the toughest times in its history over the next 50 years. But really, if we're going to make a better future happen, what choice do we have but to imagine it first?

The obvious temptation is to say things like I want a California where all children have access to health care and a top-notch education, both free; where the survival of endangered salmon is treated as more important than exporting another year's crop of irrigated almonds to the richest people in China; where families in Richmond and El Segundo and Long Beach and Pittsburg breathe air as clean as those in Malibu and Marin do.

I do want all those things. They're vital. But they're still ways of spinning bad news. Prop 13 has gutted public schools for two generations now. (If you don't think good public schools are an environmental issue, try explaining biological diversity or toxicology to someone who never had a chance to master the basics of biology or chemistry.) The powers that be in the San Joaquin Valley will spend tens of thousands of dollars printing roadside signs that blame the drought on liberals, while deriding endangered fish as "stupid." And families living just downwind from the state's oil refineries suffer higher rates of asthma, chronic bronchitis, and cancer.

All those things need to change. But describing a California that merely lacks those things and calling that a "vision for the future" is like saying your lifelong dream is to stop bleeding.

I think the best feasible future for California is one in which we react to a number of bad times that are almost certainly coming our way by coming together, dropping the hidebound adherence to the way we've always done things and coming up with creative new ways to make life pleasant in the New World.

When it comes to California's environmental future, regardless of the challenges we may face along the way, here's my hope for the California of 2064:

That Californians will care passionately about the environmental consequences of their actions.

In the future I'd like to see fifty years from now, Californians wouldn't dream of watering a lawn when they know there isn't enough water to go around for the state's embattled fish. Angelenos who considered taking a twenty-minute shower would suddenly remember the Owens pupfish struggling to survive in a dwindling slough, and they'd finish up in five minutes instead. (That's assuming, of course, that there are still Owens pupfish, but we're being positive here.)

There will be a lot fewer of us in this best possible California. Some of that will be our getting used to the idea that there will never again be enough water to support 38 million people and their lawns, their swimming pools and their twenty-minute showers. Those of us who are perfectly happy to make do with less water might stay: others will move to Ohio or Indiana or some other wetter place. California's warmer climate will also drive some folks away who tire of year-round wildfires or of hiding in their homes during the month of August.

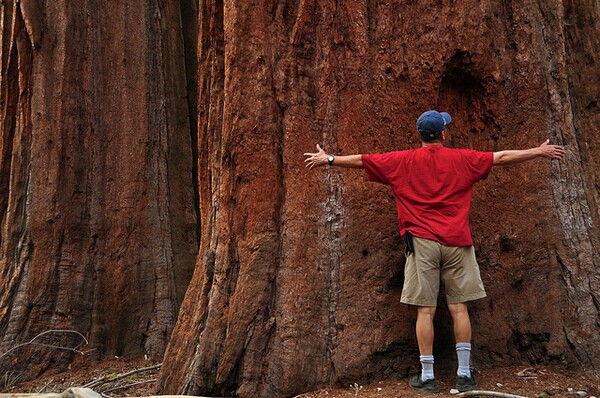

And some of the smaller crowds in this future California will result from present-day Californians deciding to bring fewer kids into this troubled world. Full access to contraception, abortion, and other reproductive health care will be absolutely essential if we want this future to happen. (That should go without saying, but these days it doesn't, so I'm saying it.) If all new Californians who arrive in the state via maternity ward are wanted from Day One, that increases the likelihood that they'll grow up to care about the place they live in. And that will be good for the billions of Californians who don't happen to be human: the salmon, the redwoods, the creosotes and packrats and condors.

More concern about the effects of our actions will mean we think more carefully about where the resources we use come from. Few coastal Californian cities could exist without extracting resources like water from other places. A future Los Angeles will likely still rely on imported water from the Owens Valley, the Colorado, and Northern California, but Angelenos will insist on making sure they don't take more than those far-away watersheds can spare. The same goes for San Franciscans drinking water from the drowned Hetch Hetchy Valley in Yosemite National Park, and people in Fresno and Bakersfield watering their crops with runoff from Mount Shasta. Whoever's left living in the Coachella Valley, which will regularly hit summer temperatures above 125°F, will have long since decided that golf courses are a really lousy use of their desert landscape.

We won't see the state's less-populated places, the northern forests and eastern deserts, as places to ransack to support our lifestyles. We'll be recycling timber and aluminum cans, and we'll need fewer clearcuts and desert landfills. Our sewage systems will hook up to biogas power plants, which means less left over for horrendous sludge disposal sites. What solids are left over will be carefully tested for contaminants, then used to fertilize dryland native tree plantations on worn-out farmland in the Central Valley, where growing oaks and sycamores support wildlife as they take carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere.

Despite the state's reduced population, our network of freeways will still be crowded. California's more than 16,000 miles of limited-access highways, with their level surfaces and their abundant sunshine, will be in huge demand as places for community gardens, solar panel shaded parks and patios, and a smattering of retail and restaurants. People who've lived in Los Angeles for a long time will know to avoid the congested 405 through Culver City, where it's nearly impossible to get a good seat for breakfast without a reservation. We'd have to keep one or two lanes open to traffic, of course, because how are we going to get bulk compost to the neighborhood gardens without using solar-charged electric pickup trucks? Just be careful of the skateboarders.

And with no more exhaust pipes in the neighborhood, the land surrounding freeways will become a lot more desirable as places to live, play, and work.

There will be trouble, as I mentioned up front. We're likely to have lost a significant part of Stockton to floods by 2064. The same goes for valuable real estate along the shore of San Francisco Bay, and ecologically important land alongside a number of other estuaries along the coast. By then, it will be obvious to all that the sea will rise even farther, and the arguments will shift from whether or not climate change is real to which parts of coastal California do we try to preserve. Should we save downtown Long Beach, or help it transform itself into the fish nursery wetlands of 2264? Some places we'll attempt to wall off for the time being, perhaps with concrete rubble from the freeways we decide not to use as garden corridors. Others we'll be working to abandon, to move any crucial infrastructure there to higher ground, and to plant salt marsh plants atop the former parking lots.

The streets that remain will be full of wildlife. Black bears will reinhabit the suburbs, and they may follow the coyotes of 2014 across the Golden Gate Bridge to colonize San Francisco. Deer will become a nuisance, drawn to our precious lettuce patches on the 101, and we will quietly wish the thriving wolf packs roaming the north state from Modoc County to Yosemite would head south to Glendale. There will be a quiet, technically illegal, but thriving trade in locally sourced venison.

Some of the more impatient of us will quietly hatch a plan, and a dozen trucks with dangerous, tranquilized cargo will make the long journey south from Alaska. The trucks will later be found parked in four feet of water in downtown Stockton, the brine long having removed any telltale fingerprints. Four months later the first reports will come in of Sierra Nevada bears larger than usual, brown and shaggy, with shoulders broad enough to fell trees. The authorities will scoff at the rumors. They'll say there's no credible evidence of a return of the grizzly to California. The scientists will debate.

In the Sierra, a mother with cubs will amble through a grove of impossibly large trees to the cache she made a week before: a Roosevelt elk's hindquarters. The largest of her cubs will attempt to scale one of the huge trees, will make it ten feet up before realizing its error. It will bawl in alarm as it tries to figure a way down. The tree was two thousand years old when California first became a state. Its trunk, nearly 25 feet across where the cub hangs on for dear life, is three inches thicker than it was in 2014. There's no reason to think it's won't grow a foot thicker still.

It's hard to imagine a rosier future for California than that.