Barbara Bestor: My SoCal Art History

The history of art in Southern California isn't linear; it is a fluid, multi-angled continuum made from the personal experiences of many artists from myriad backgrounds. So to trace the trajectory of Southern California art, Artbound is creating a collective timeline comprised of the decisive events that shaped artists' creative development. We hope that in the space between these personal histories, an impressionistic view of Southern California's art history will come into focus.

Today we talk to Los Angeles artist Barbara Bestor.

Barbara Bestor: "Kiss Me Deadly"

"Kiss Me Deadly."

How has noir film shaped how you view Los Angeles?

I have Kiss Me Deadly on my list because it's a kind of later version of film noir that I think bridges the whole idea of L.A. noir and atomic parallel and maybe something that kind of sets the scene for something you can call the punk rock attitude of L.A. later. So for me it's the movie I saw probably in the mid 80's. That movie in particular starts in the downtown area which some of the older noir which is more New Yorky, which is shot on a New York set or something like that. It kind of moves from there to the more suburban west L.A. kind of sprawl condition and you get this kind of darkness that starts to permeate the suburbs and that I think is really interesting, architecturally and aesthetically.

Early noir films often depicts buildings that no longer exist, how do you see noir interacting with L.A.'s built environment

Sometimes there are real buildings in noir stuff like that. I think The Big Sleep takes place on Vermont Ave. and some of the actual stories were taking place there. The way that the city worked is almost as if it were already nostalgic for an East coast urbanism. So much of L.A. as we come to think of it was that other more sprawling, open ended, car driven, metropolis and so I think there are two things, there's the architecture like the literal architecture strain in terms of buildings and atmosphere, that sense of the city as a place that hems you in. But there's also the idea of the noir as a necessary balancing act with sunshine and that kind of sunshine noir thing is what is particularly interesting about L.A. And film noir does such an excellent job of providing that sort of psychological darkness of American urbanism in general. L.A. specifically often deals with that combo like the sort of bathing beauty by the pool drinking a cocktail who then gets sucked in the dark underworld. That's sort of what the city is a little more like. It's kind of back and forth.

Is that back and forth expressed in your practice at all?

People would look at my work and think it's more heavily on the sunshine side of the table but to me the necessary precondition is the noir. I think in architecture it's very necessary to understand that all architecture comes out of destruction. You can't build anything without destroying something, whether it's a tree or a piece of land and that self-knowledge in architecture leads to a kind of self-consciousness that I think leads to better buildings because it gets more self aware. I'm not like a boisterous sunshine person.

The Schindler House.

With such an array of architecturally intriguing buildings in L.A., why did you pick the Schindler House to single out?

The Schindler House has a lot of layers. I have a lot of relationships with that building. It was probably one of the first sort of architecture experiences that I found incredibly moving as a space. Something about the combination of the scale. It's one of those places where Schindler was still using the radian idea of compression of space. You sort of enter these kind of short, low, dark things and kind of come into something that opens up. It doesn't actually open up this way like a Wright building might. It kind of opens up panavision style, horizontally like a Japanese opening. So I think there is a spatial experience. And also it has, planimetrically, like it creates a very complex spatial experience or like the main entrance points kind of put you in these weird places in the building. But then it has this amazing sort of sociological history as a house built already for two couples and their artistic creative space. It's very much messed with and maybe kind of presages kind of some of what we have now in terms of you know co-housing ideas. I got married there so I kind of have an attachment to it for that but I sort of got married there because I like the building so much and that I think on a purely architecture level the tectonics of it, the way that it's these big concrete slabs are poured on the ground and then tilted into place - totally unprecedented reallyand then also again weirdly related to all the concrete warehouses in San Fernando Valley. They're all titled up concrete. Schindler was one of the first people to do that and that was in 1920. Long before it was adapted into industrial kind of building.

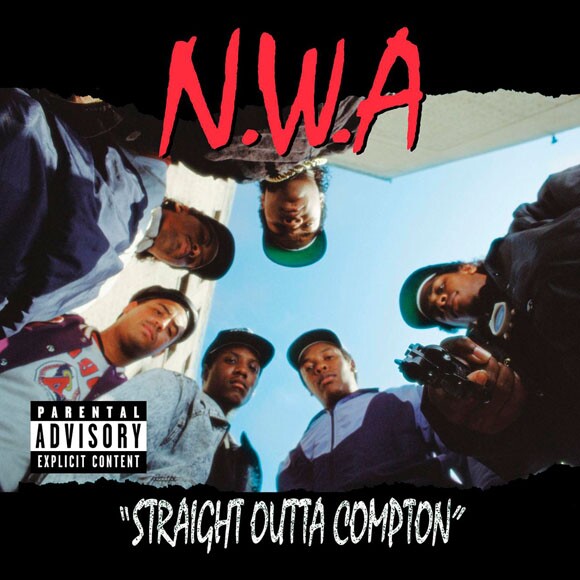

N.W.A. - "Straight Outta Compton"

What about this group and this record influenced you?

You'd have to put N.W.A as one of the big poster boys for that kind of radical creativity that L.A. has engendered. When I first moved here, it was the late 80's and there was this radio station KDAY that played current new music from the streets or whatever and I got super obsessed but they were really like the local band and so we would go see them at this place called World on Wheels. There was this band that then that was making all these songs that were like gangster rap lyrics but also like musically sampling really incredibly interesting stuff and the people from that band went on to do all this stuff. Dr. Dre, I think like this crazy big figure in the music business now. Ice Cube was someone. I used to have a poster of Ice Cube on my studio when I first opened my office. To me I find musically that a lot of west coast hip hop sound has been kind of like a soundtrack for what i'm thinking about. I consider it part of the kind of urban condition that I work in. I think as a moment, like lets say hypothetically that rap at that point took over the position of punk rock as a radical musical output like that to me marks that transition.

What else forms that urban tissue that you investigate in your work?

L.A. has all these layers of coexistence like the Chautauqua Palisades emigre creative crowd like Theodor Adorno, on the one hand, and Thomas Mann and Schoenberg all that kind of stuff. I think that musically I probably liked Black Flag about as I liked N.W.A within a 5 year period but those are kind of these other layer that were getting kind of being part of tissue the neapolitan or whatever of L.A. culture. I think it's precisely that coexistence and the the kind of flicking energy that runs between these different things whether it's music stuff or movie stuff. That's a lot of what generates this energy that has attracted a lot of creative people out here and I would say that if I was like a practicing gallery artist person probably that's part of that energy. I don't think it's an accident that Cal Arts turned out all the big art stars at one period and you know now it's kind of mixed between U.C.L.A. and Arts Center but these are kind of...it's a very good milieu to exist as just an individual living your daily life you just get all these different layers.

Kustom Kar Kommandos.

This seems to be about finish and fetish. How has that influenced your architectural aesthetic?

I think the Kustom Kar Kommandos is the extreme like high art version of something that I was trying to sort of put into the list in a general way which sort of includes everything from resin fetish art to low rider culture. To me some of the big things coming out of that are color, and the idea of the glossy, like smoothness inform as this kind of achievable desire like almost achievable and people's own garages that you can kind of create these remarkable objects and that you know I personally like a lot of gritty stuff as well like the sort of raw material thing I'm into but in a way it's like juxtaposition that I kind of think that a lot of the stuff in the PST's shows lately. There was one remarkable that was in San Diego the phenomenal show and that had some of the some of the like smoked resin glass pieces or smoked regin non glass pieces and trial pieces those are these are fetishistic getting a certain kind of color, quality, or trying often concretize translucently. I think people do that in their cars as well as in art galleries that's something I'm interested in a building. I'm not necessarily interested so much in these shiny glossy object building departments but in the translucently dematerialization camp would be something I'm interested in. So that sort of involves like colors and mirrors and other things that make sometimes undermine the salinity of something as a legible object and take advantage of the natural light of L.A. cause you kind of need that bright light in order for all these special effects to happen, but that movie is incredible.

The Mike Kelley Retrospective at L.A.C.M.A. in 1994.

Is there a particular Mike Kelley piece that resonates with you?

Mike Kelley, who tragically died last year was the author of this piece called "More Love Hours Than Can Ever Be Repaid" that was a big feature in his retrospective at L.A.C.M.A. awhile ago. He was a really influential figure in L.A. art, I think to at least younger generations of artist. His work brought in all these other kinds of content of often darkness, like he would be a noir guy but also using mean of expression that could be found objects, collected things. So I think "More Love Hours Than Can Ever Be Repaid" is this work that for me anyhow, I'm not alone on this one, has brought a lot of emotion to a piece that in a way that was very transformative. The meditative purpose of that presence of the person who is making it for whatever reason even it's a kind of you know messed up stuffed animal, but his piece there, I felt like it brought like psychology back into what was maybe before minimalist and conceptual art like it brought this sort of searing psychological connection and I think that whole show which is also related to the whole punk rock scene. His work covers a lot of different areas that that I feel is kind of more like the beating heart of some of the drive behind making things.

In what way does that exhibition inform us?

A lot of art that is minimalist or conceptual which is stuff that architects like a lot, you know we practice a fair amount of detachment. You can kind of go out and use weird yarn toys and get this sort of impact or and actually access this content that wasn't accessible before. As a retrospect of a show like that, that was sort of an earlier version of how little bits of pieces of things can also add like can accumulate into like this sort of giant masterpiece.

Dig this story? Sign up for our newsletter to get unique arts & culture stories and videos from across Southern California in your inbox. Also, follow Artbound on Facebook and Twitter.