El Teatro Campesino, Collective Creativity, and the Cinco de Mayo Run

Los Angeles, May 4, 1971: It's a wet Tuesday evening at Occidental College. In the outdoor theater "El Soldado Razo," a new acto byTeatro Campesino (Farmworker's Theater) is reaching its climax. A soldier writes to his mother on one side of the stage. On the other -- half a world and days away -- his mother reads from the same letter.

Olivia Chumacero was there. She was a farmworker and Teatrista from 1969-1983, and sets the scene: "The mother is standing and the soldier is standing. They are reading the letter as if to each other and he is shot in the midst of him writing the letter, as she is reading."

The audience "sat stunned and shocked," wrote L.A. Times reviewer John Weisman. "There were sobs followed by a standing ovation."

With the Vietnam War raging and Rubén Salazar less than nine months dead -- killed by a Sheriff's Deputy during a 30,000-strong East L.A. Chicano Moratorium march -- El Teatro had done it again: "made the people stop and think -- the primary objective of a successful acto."

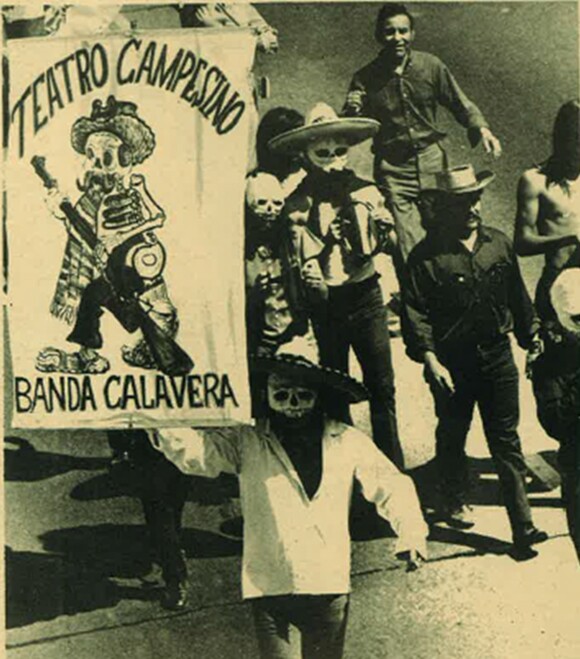

El Teatro was in L.A. for its annual "Cinco de Mayo Run." Through the 1970s and early 1980s the company, which had originated as a propaganda arm of the nascent United Farm Workers (UFW), funded itself largely via twice-yearly tours to L.A. Every May it focused on colleges ("our bread and butter"), and around September's Mexican Independence Day "we would hit a lot of cultural centers and communities."

In September 1971 El Teatro returned to L.A. as usual, this time to participate in TENAZ (Teatro Nacional de Azatlan), a ten-day theater festival featuring fourteen Chicano troupes. Once again "El Soldado Razo" moved its audiences to tears.

Reviewing the festival for the L.A. Times, Gregg Kilday wrote: "Teatro Campesino no longer stands alone as California's sole exemplar of Chicano guerrilla theater...[it] has now become the senior partner in a network of Chicano theater troupes scattered across the Southwest."

The network had grown quickly. Although it was rooted in the tradition of Mexican carpa (tent theater), the "senior" Teatro was still only six-years old in 1971. It had emerged from the Delano Grape Strike, a five-year UFW effort to achieve union recognition and fair wages and conditions.

Recalling a conversation with UFW leader César Chavez shortly before he died, Chumacero reports that "César's idea about creating carpas so that we could go out and inform the people," sowed the seeds of El Teatro. They were nurtured by farmworkers Felipe Cantu, a trained carpista and "the funniest man I ever met;" Agustin Lira, a young musician; and Luis Valdez, a Delano farmworkers' son with a history of theater experience."

In the beginning the "entire focus was to deliver the message about the Union," and El Teatro performed its boisterous actos in the fields on the back of a truck. As time went on though, "people had other visions and other artistic goals." Chumacero recalls: "By the time I came into the picture in 1969, the theater company was no longer just another arm of the union, they were in Fresno and the material that they were covering was broader. It was bilingual education, it was violence, it was the war in Vietnam."

"El Soldado Razo" was first performed in April 1971 at a Chicano Moratorium event in Fresno's Roeding Park. Although, as scholar Randy J. Ontiveros points out, the actos "have wrongly been institutionalized within American literary history as the solitary work of Luis Valdez," they were in fact, authored collectively. "El Soldado Razo" was no exception:

"It wasn't like an individual going to their home and writing a full script," Chumacero explained. "We would have weekly meetings to discuss politics, social issues, and state of the art as far as performing, and in these discussions we'd begin to hone which idea we'd be working on next."

"At that time the draft was in full force. It permeated our lives." Chumacero recalls. "Juan Gomez was drafted and he was at the cusp of not being able to pass the physical because he was so thin. Other people in the company had cousins, brothers, and other friends that were gone, so we started having just a discussion about that reality. And we had a deadline, we had to perform at a demonstration in Fresno."

During this period, company director Luis Valdez "was teaching at UC Berkeley. So it was left to us to create.The idea came to us to just do the personal family situation. So we did it with him [the soldier] going away, taking a Greyhound bus and that one moment when you have to say goodbye, the parting; all of which we improvised."

"At that time, letter writing was the way to communicate with people, and so you would actually share if you received a letter from your brother, your cousin, your friend. We would get together and read those letters to each other."

"Luis would come and see where we'd gotten as far as the improvisations. So much of the dialog would come out of our improvisations. Or we would sit down and actually write. We were writing letters as if. Luis had the final say so when it came to everything that was blocked on stage. [He would] orchestrate everything in a magical way. He came up with the voice of the narrator. And the specific thing that he did write was the two-letters. The mother is standing and the soldier is standing and they're reading the letter as if to each other."

With "El Soldado" added to its repertoire, the company piled into vans and trucks for the 1971 Cinco de Mayo run. Everyone carried a sleeping bag, and his or her own costumes and props. "You took care of everything yourself; you mended your stuff, you replaced your makeup, all of that, you were responsible. There were no prima donnas. No one [was] in charge."

Teatro Campesino's rasquache (underdog) aesthetic, "which says that you do with what you have, and you do it to the best of your ability," was a matter of both allegiance and necessity.

Throughout Chumacero's fourteen years with Teatro Campesino, the company was "completely self-sustaining. Everything that we made from the performances went back to the company. Initially we weren't earning anything and then eventually I went on salary and I was earning $30 a month. You had a roof, and food, and a little bit of whatever you needed, but nothing major. The focus was entirely a collective decision to generate the funds, and then bring them back to be able to live, and create, and continue working."

"As time went on," Chumacero continues, "it evolved more towards classical theater." [After the 1981 film] 'Zoot Suit' he came back with the idea that he was going to change the Teatro, and he wanted to formalize everything. Everybody had to audition, and you had to present your resume, and your headshot and all of that, and you were not part of the collective writing process."

"Well," she continues with a laugh, "I am good at improvising. To me improvising is just another way of survival [and] improvising on stage was another way of just being completely alive. And when you're alive, and you're having to make decisions, everything that you've learned and everything that you've experienced comes to the forefront. So here was a process of creating where you could do that over and over again, with others, and create beauty, and vibrate, and have this sense of commitment and love to the work.For me [the formalization of El Teatro] was like a closing of doors, not a continuity of creativity. I left the company in 1983. To this date I don't have a headshot up there with everybody's."

Back at Occidental College in 1971, Olivia Chumacero was on stage. John Weisman describes the scene: "Death, dressed as a Franciscan monk with a skull's head and an endless number of disguises introduces the characters: Johnny, who is going off to fight in Vietnam. Then Johnny's mother, his girl, his father, and his 'carnalito,' - his friend. La Muerte toys with the characters, speaking for them while they mime the words. And all the while La Muerte is laughing, because he's made it clear at the play's outset that Johnny is going to die; that the whole process of seeing him off is an empty charade."

The teatristas are performing for their bread and butter in the rain.

Dig this story? Sign up for our newsletter to get unique arts & culture stories and videos from across Southern California in your inbox. Also, follow Artbound on Facebook, Twitter, and Youtube.