Graffiti Scrolls Enter the Getty's Canon

The graffiti scrolls of Los Angeles have been delivered.

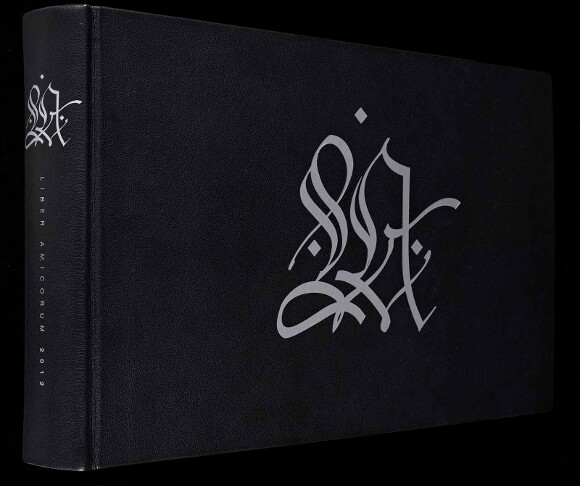

Handsomely bound into "L.A. Liber Amicorum: Book of Friends," the 143 works on paper by Los Angeles-based graffiti artists were presented this month. The project was conceived by collector Ed Sweeney, who approached the Getty with the idea of assembling a monumental "piece-book" that would represent the works of regional graffiti artists. The idea grew into a scholarly interpretation of a journal when a handful of artists met with David Brafman, Curator of Rare Books for Getty Research Institute, who introduced them to a collection of books with histories of writing and emblems.

When Brafman was introduced to idea of compiling a black book, he immediately thought of some of his favorite Getty rare book acquisitions. "The liber amicorum, which translates into 'book of friends,' was a 16th and 17th century fad," said Brafman. "Like a yearbook, you have these blank bound books and you go around and get people to add a coat of arms, or a painting, or a poem. It becomes part of your social identity and your networking."

The artists took to the idea and helped recruit other artists to contribute works. Then the pages began trickling in. The outcome is an emblematic journal filled with visual forms that reinforce Los Angeles as a center of street art's visual linguistics.

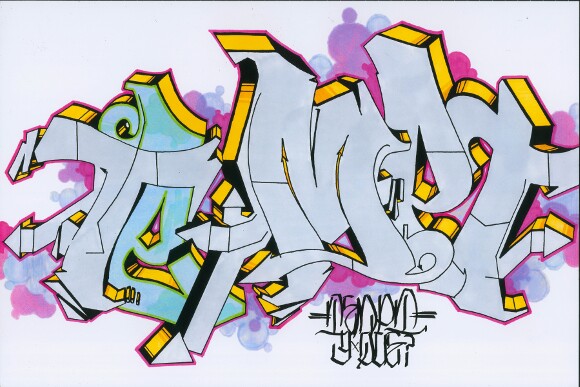

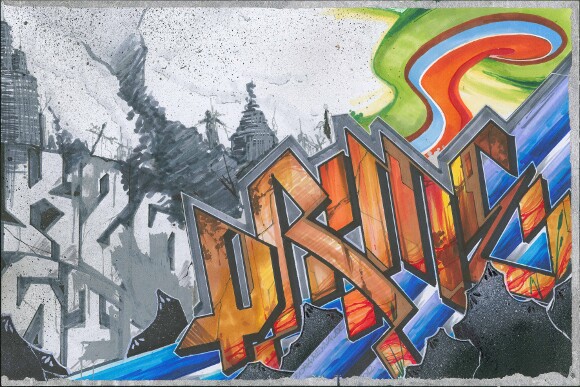

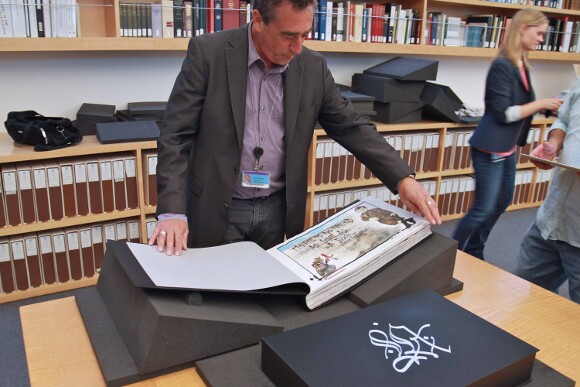

Some of the artists in on the initial meetings, including Angst, Axis, EyeOne, Defer, Prime, Push, Man One, and Saber, were in the Research Library at the Getty to get an early look at the completed black book, which is also titled the "Graffiti Black Book" and "Master Piece Book Project" to make web searching easier.

With a cover that simply says "L.A.," a regional claim in elegant calligraphy designed by Prime, Brafman slowly turned the pages of the black book. As if in a meditative state, the gathered artists looked at the work of colleagues and rivals, their aloof aura replaced with nodding and commenting. The artists -- who use one name to sign their works -- used one word reviews when a strong contribution was revealed, saying "nice," "yeah," or "crazy." A few times there was a synchronized lean over the table to take a closer look at a piece that caught their eye. An impressive entry would be measured with a soft chorus of "wait," so that the artists could take a photo with a cell phone or iPad.

An entry by Axis is the first page of art, and he uses a quote by Hemingway to introduce the book of friends: "There is no friend as loyal as a book."

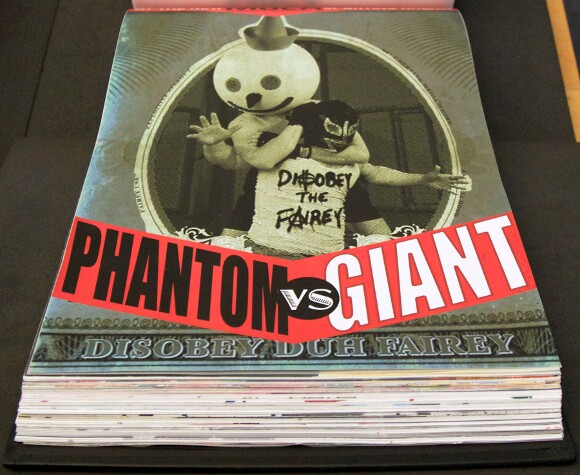

Retna sent in his monochromatic hieroglyphics as a detail to his larger works, and Patrick Martinez refers to his imagery of idyllic palm trees on fire. Man One used letters to represent the foundation of graffiti and drew in graphite to directly simulate his sketchbook method. The Phantom made his battle against what he calls "street art hubris" part of the archival record.

It's a dignified entry into the Getty, and the academic and aesthetic exercise challenges how graffiti has been interpreted in galleries and other museums in the past.

While The Museum of Contemporary Art surveyed graffiti with "Art in the Streets," it failed in scholarship, said Angst, a veteran of those same streets. "It was just a spectacle," he said of the 2011 exhibition at MOCA. "It attracted people, and they had a good time, and that was fine and dandy. But it was a missed opportunity."

"Generally when art is making the rounds and moving up the ladder to legitimacy, by the time it enters the museum, one of the reasons it enters the museum is so that the curators and scholars can place [it] in the canon of human civilization," said Angst.

This book is a document for study that will help graffiti -- beyond the Los Angeles contingent. "Scholars can write about it within the context of art history and within the entire canon of art of human civilization," added Angst, who feels it's important to have this art surveyed at this stage. "For the artists and the work, the legitimate scholarship will look at this work and see how the artists got it to where it is now."

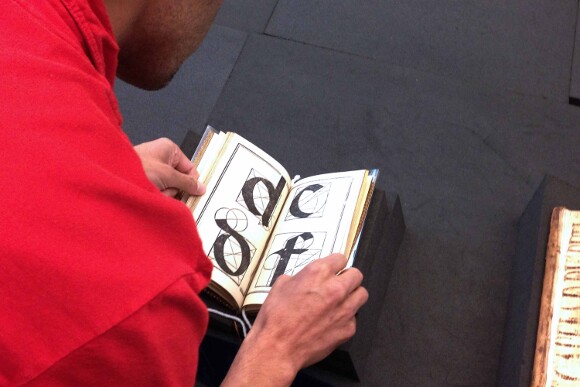

With "L.A. Book of Friends" on one side of the room and a small display of rare books on the other, generations of text imagery jumped from table to table. Gravitated to the details of letterform printed from woodcuts, the practitioners of urban typography studied the line strokes and measurements that formed ascenders, descenders, and curves printed on paper by wood blocks, direct design descendants of Leonardo da Vinci.

Prime stood over the table staring at P's and Q's, while Saber took a magnifying glass to a page filled with ornamental borders. The other artists stood by, again commenting as a page was turned.

"They identified with letters as an artistic element," said Brafman. "That may be a cliché about street art and graffiti in general, but I don't think you can really overemphasize what it means to think of a letter as a part of line, color, and form, and how it designates meaning."

"The other thing I saw was that people were attracted to Renaissance books about geometric form, emblems and symbols. That was what they [viscerally] understood, that fundamentally that was the artistic tradition they are part of," said Brafman.

When art historians look at any of these 143 artists' technique and practice, it can also add meaning to how artists respond to the city. "What it says is how vast Los Angeles is. Los Angeles has space. Los Angeles has light, and Los Angeles has horizontal vistas that no other city has," said Brafman, who regards the art as different from a wall painting, mural, or subway tag in New York. "There is a fundamental difference in the use of color and perspective in these works, because L.A. is a vast horizontal town with the most beautiful natural light in the world --- and the most beautiful darkness in the world too."

It's also a record of a book curated by the artists, who insisted the works on paper be bound together before being exhibited as single sheets. "They wanted to be part of the project," said Brafman. "That rival Los Angeles street art crews were all bound together in 'L.A. Liber Amicorum, Book of Friends' -- that's the most important thing about this project."

Dig this story? Sign up for our newsletter to get unique arts & culture stories and videos from across Southern California in your inbox. Also, follow Artbound on Facebook and Twitter.