How a Santa Barbara Artist Uses Digital Art to Spread Chicanx Pride

Art has served various functions for Santa Barbara artist Adriana Arriaga.

As a high schooler recovering from an eating disorder, Arriaga decided she'd become a graphic designer to challenge the heavily-Photoshopped portrayals of "beauty" in popular, 2000s-era media, the very depictions that contributed to her own health condition.

"I remember looking up who's responsible for Photoshopping women and the [beauty] standards we were seeing growing up as Millennials," she said; Seemingly, every model was "super thin, with light skin."

In college, Arriaga's mission was further clarified. She took a Chicano Studies class at Santa Barbara City College, where she learned the histories of Chicano people, elders, artists, immigrants, activists and community leaders — her first time learning about it even as a Chicana herself.

"I realized I didn't even know any of this history," she said, a complicated but motivating realization.

"I thought, 'What I can do with graphic design is a lot bigger than I initially thought.' So, I connected graphic design and activism. I started taking ethnic studies courses and design courses, trying to figure out how, when I'm doing a project, I can spread the message of [Chicano pride] that I'm learning now."

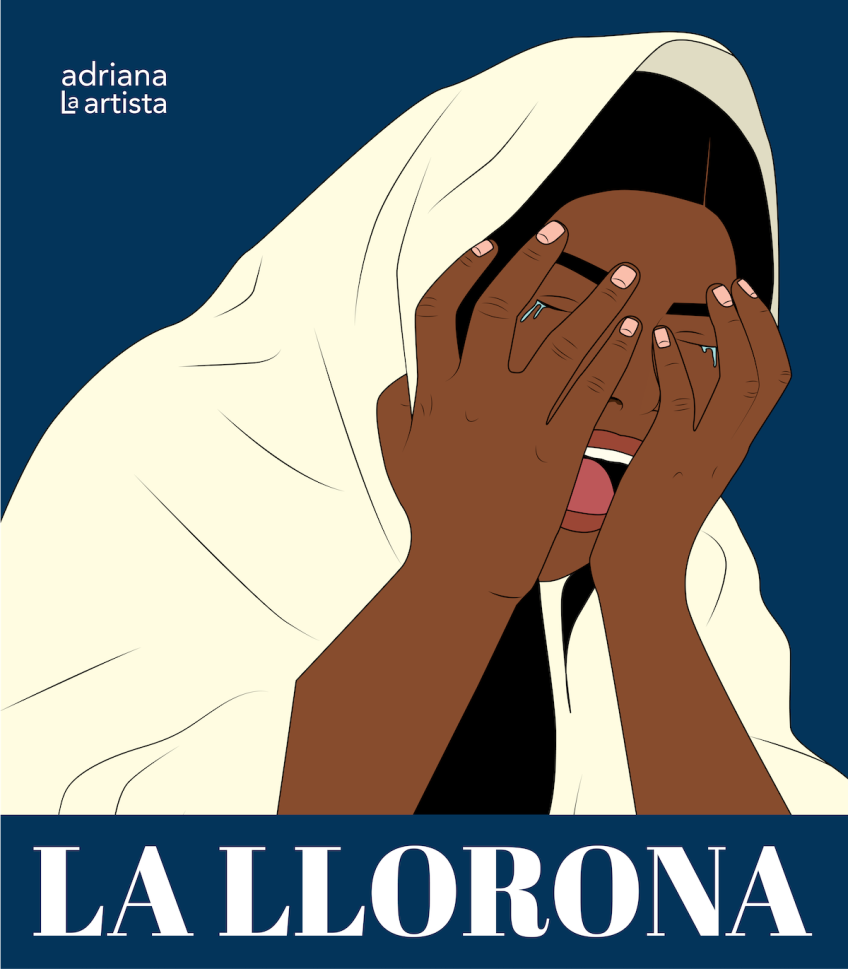

Today, Arriaga, 27, continues an expanded version of this intention in her art. A self-proclaimed Xicana who goes by adriana la artista, she creates digital pieces that can take the form of prints, posters, stickers and even wheat paste murals.

"With every poster make, I have a story to tell," Arriaga said. "It's always gonna be through an experience I've had in the past or my reactions to things happening now."

She's created posters for community causes proclaiming "Protect mujeres in the fields" and "Honor the hands that feed" in honor of farmworkers; her "Not your home girl" T-shirt was a direct response to an unwanted Instagram message from a man addressing her as such. In other pieces, Arriaga depicts herself as nude, often juxtaposing pride in her sexuality with her religious upbringing, symbolizing pressures she grew up with to be "a good Catholic daughter."

"Unfortunately our religious environments put us [women] on a pedestal, about how we should behave and how we should act," she said. "Rebelling against that through sex, I do it for myself. And to show we deserve respect regardless."

Throughout grad school and her professional career, Arriaga has defended her craft to those who claim digital art isn't "real art;" in grad school for design, she argued that Chicano art is both design and art, as its beauty also serves a function. For her, "the purpose of each Chicano poster was to build community."

Unfortunately our religious environments put us [women] on a pedestal, about how we should behave and how we should actAdriana Arriaga

"I kind of live my thesis, proving to folks that when we create these posters, it connects to us as Chicanos living in between, going back and forth," she said. "[The art] can be in the museum or on the street."

Arriaga proved this last year when she and fellow Santa Barbara artist Claudia Borfiga implemented a large mural at Paseo Nuevo mall. The bold, colorful piece reflects Borfiga's inclination toward depicting natural Earth elements and Arriaga's inspiration found in her culture and local community.

"The older hand represents knowledge being passed down…the butterfly is a motif used to symbolize migration…the hummingbird is popular in Chicano imagery," Arriaga said, and the sea kelp and arroyo toad are local creatures.

"And lastly, the woman — it was important to me to have Mother Earth in it…she's a woman who, for me, was inspired by the Indigenous women in my life who have taught me so much about protecting the Earth."

Especially during the pandemic, Arriaga has been inspired by community efforts to support one another in big and small ways. She often uses her art to advocate for local causes and has recently been collaborating with a community collective that has grown organically in town. The group consists of artists, creators, teachers, activists and others along the Central Coast and even as far as New Jersey, providing support and connecting each other with opportunities and potential project collaborators.

"We're kind of enjoying the journey, figuring out what we need," Arriaga said. "Artists…we can't do things alone, we have to collaborate."

Arriaga had a recent art show called "Heaven or Hell," held with fellow Santa Barbara artist Baby Moet at local vegan restaurant Rascal's. She showed two pieces meant to fit the "heaven" theme, one titled "Bless You," a depiction of Arriaga dressed as la Virgin de Guadalupe clad with large gold hoop earrings and a fresh manicure, and the other called "Death of a Conquistador," which shows Arriaga holding a knife to the throat of Spanish conquistador Hernan Cortez, a piece inspired by Artemisia Gentileschi's piece "Judith Slaying Holofernes."

Together, the works symbolize Arriaga's journey as an artist and as an individual: a homecoming to self, a removal of imposed beliefs and a reclaiming of cultural pride and traditions in community.

For me, it's not even just disassociating myself from colonial ideology, but destroying it.Adriana Arriaga

"The ideas that colonialism forces on us, and how it's ongoing…it appears in different forms even today," she said, "so, by reclaiming my dignity and calling myself Xicana, it's about looking at the past and trying to embrace what my ancestors did and what we're doing now as a community, whether it's through our language, food, behaviors, what we're reading, cultural practices. We're really trying to save and share and teach, and through doing that we slowly begin to decolonize and reclaim our identity in history."

"For me, it's not even just disassociating myself from colonial ideology, but destroying it," she continued.

"I'm no longer confused about who I am."