How the Rise of Instagrammable Art Changes the Experience of Art

I searched for the hashtag #desertX on Instagram, found it, and then followed. When I have the Instagram app on my phone, I probably check it at least once an hour, randomly, like most of us who have it do, in those moments where previously we would’ve had time to space out or just sit there. With Instagram on my phone screen, I am easily sucked in. I aim for mindfulness, but also accept the reality of my distractability. I’m just scrolling, man! Most recently in my feed, I saw top posts from #DesertX alongside pics from my friends’ lives, art museums, newspapers, artists and the Kardashians, all of whom I follow.

While Instagram may be helpful in seeing art that you couldn’t see because of, say, geographical or financial barriers, the experience of scrolling can also just become a distraction, and when this happens the artwork can come off as merely spectacle. To blame Instagram for this, however, is too short-sighted. As with anything seen online or through apps, it’s possible to learn more about the art with some persistence and a desire. Sometimes, that means detaching from Instagram altogether. It’s a 21st-century conundrum that art museums, artists and art fans everywhere are dealing with, especially when a lot of new artwork is discovered on Instagram. Kanye West started reblogging artist Devin Troy Strother’s Tumblr, which jumpstarted his art career. LACMA’s Michael Govan discovered Guadalupe Rosales’ work at an art gallery, but her work is an Instagram account. She ended up becoming the museum’s first Instagram artist-in-residence. Amalia Ulman’s performance project of interrogating stereotypes of girls on Instagram led her to become a celebrity on the platform.

Aside from artists whose works are on Instagram or were discovered through social media, the 2017 Desert X event outside of Los Angeles is a prime example of potentially Instagrammable art. I didn’t get to it, but I did continuously enjoy other peoples’ pictures of Doug Aitken’s “Mirage,” a single-story ranch-style house without doors or windows that’s made entirely of reflective mirrors. At times, it blended in so well with the landscape that it literally became another mirage in the desert.

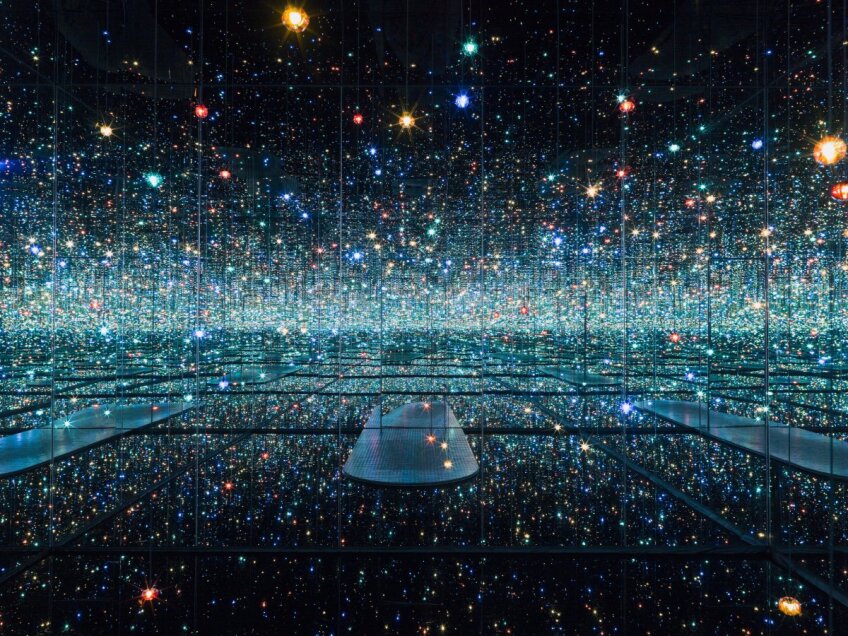

The people who visited this piece and posted images of it to Instagram also made it a space for self-reflecting on the idea of self-reflection, of selfie-ing and of being seen. Or rather, that’s how “Mirage” appears on Instagram. Pictures of it continue to be top posts in the #DesertX hashtag. It is a mesmerizing reflective structure, casting the sort of infinite mirror/mirror-ing that is also found in Yayoi Kusama’s “Infinity Mirrored Room” installations. Many of these mirror images with artworks are selfies.

“The selfie is a continual piece of content, yet once posted it is also immediately archived within the network, to which the user licenses their image for repurposing — an infinite mirror loop,” I write in my new book, “The Selfie Generation.”

Mirrored artwork like Kusama and Aitken’s pieces become constant feedback loops, and they’re fascinating to watch. In effect, because these pieces are mirrored surfaces, there are two parts to the works: The pieces as they exist in the physical world, and the pieces as they exist through the eyes of social media users (on the ‘gram, FB, Twitter, Snapchat, etc.) as versions of a selfie.

Mirrored art before the rise of Instagram

While some argue that Instagramming the art actually ruins the art experience, in my book, I argue that social media and selfie culture add another layer to the experience of the art which is radically different from how art was experienced before the rise of the smartphone’s front-facing camera. The selfie is a mirror, an aspirational image, a way for others to see you online, a mode of self-expression. But, those who are millennial and remember a time before smartphones and museums became one — folks who are GenZ probably don’t know this time at all, sorry! — can reflect on what it was like to experience a mirrored room or mirror house without the selfie.

This becomes especially complicated with works like Kusama’s “Infinity Mirrored Room,” which did exist before social media, whereas Aitken’s “Mirage” was made after Instagram became a thing.

“I’ve known Kusama’s work since college, before Instagram and the selfie existed, and I think that there’s an element of her work that is being lost or pushed aside when it is used as only or primarily an excuse for a selfie,” said Andrea Gyorody, Assistant Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art at Oberlin College’s Allen Art Museum. “I saw an infinity room of hers, before Instagram and before I had a smartphone, at least a decade ago, and you are in the room alone contemplating your body in the space and the infinite reflection, and it’s different when mediated by a camera.”

At the same time, exhibitions like Kusama’s are bringing people to the museum, if not to see the art then to just get a selfie and have a moment of self-expression within the art installation.

“It’s this perfect time with Kusama and Instagram hitting its own stride,” said Chris Cloud, a Minneapolis-based artist with a practice focused around social media. “People are like, ‘I have to get tickets to this show,’ they’re like ‘I’ll go to L.A., tickets to the Broad, just to take a selfie.’ Some of them have limited time, like 90 seconds in the space.”

That sense of an experience without the smartphone seems to be part of a bygone era, like the days of going to your local video store and paying $3 to rent a movie — and that’ll be $6 if you’re a day late, which is almost the cost of an entire month of a Netflix subscription. No wonder it now feels like Netflix ‘n Chill or nothing.

Art museums’ Instagram conundrum

For fine art museums, the rise of Instagrammable art has also forced them to compete with places like the Museum of Ice Cream, which has locations in San Francisco, Los Angeles, and Miami. The New York run of the Museum of Ice Cream last summer quickly sold out.

But let’s look at the numbers.

While the Museum of Ice Cream may only have 337K followers, it’s endlessly hashtaggable —there are over 132,000 posts with #museumoficecream on IG — and ripe for selfies or impromptu photoshoots. Two kids chill out in the lollipop room, surrounded by oversized gummy bears and giant colorful candies. A girl stands in a pool of sprinkles and throws them into the air, a look of exuberance on her face.

The Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco has had some competition from the Museum of Ice Cream. “Klimt & Rodin: an Artistic Encounter” (Oct 14, 2017-Jan 28, 2018) sold out the final weekend of its run, with attendance numbers of 186,807, but it certainly wasn’t as Instagram-worthy as “The Summer of Love Experience: Art, Culture, and Rock & Roll” (April 8-August 20, 2017), which brought in 265,310 people and also offered tie-dyed psychedelic type rooms perfect for Instagram-hungry visitors. Yet how much of the actual social media presence translates to visitors?

“We are currently conducting visitor surveys to get a better understanding about and hard data on how social media impacts our audiences,” said Francisco Rosas, Public Relations Associate at Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco (de Young and Legion of Honor).

Not every museum is so selfie shy. Some are explicitly focused on the visitor’s selfie/social media experience, so as to never make anyone feel bad for selfie-ing in the museum. And anyway, selfies and social media posts are one mode of self-expression.

Places like the world’s first selfie museum in the Philippines offers artworks that are also meant to be selfie-d with. The new Museum of the Selfie in Glendale, which encourages visitors to selfie there as well as learn about the history of the selfie, tracing its roots to self-portraiture, which was also the topic of my selfie column for Hyperallergic.

“The selfie is contentious and controversial because its boundaries aren’t known yet,” I write in the introduction to “The Selfie Generation.” “In the age of social media, the very existence of the selfie has raised questions about how much of peoples’ lives should be shared on the Internet and social media.

It’s a decision to take a picture with art, or take a picture with art and share it on social media; it’s another to just go and observe. In the age of art that’s easily Instagrammable, the social media posts about a work of art lend it another type of experiential meaning and offer an additional viewing experience. At the same time, this can create a spectacle of the work if the artwork is not further investigated. Obviously, just because you’ve seen something on Instagram doesn’t mean you’ve seen it IRL. That is a different experience altogether.

Click through a selection of Desert X installations from 2017 below:

Top Image: "The Circle of Land and Sky" by Phillip K Smith III | Still from Desert X