'No More Japanese Wanted Here': When Japanese Americans Were Forced Into Internment Camps

It was extremely moving to visit the Japanese American National Museum (JANM) on the 75th anniversary of Executive Order 9066, one of the most shameful moments in this country’s history. On February 19, 1942, just two months after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, President Franklin D. Roosevelt drafted an executive order requiring men, women and children of Japanese ancestry to move to relocation camps. A series of civilian exclusion orders were publicly posted all along the West Coast with the title, “Instructions to All Persons of Japanese Ancestry,” notifying Japanese Americans of their impending forced removal. To commemorate 75 years since the order, JANM is presenting the exhibition “Instructions to All Persons: Reflections on Executive Order 9066,” which features important documents from the National Archives, art by Japanese American artists and performances highlighting current political parallels. Though the exhibition focuses on historical events, its message is clear: we must be very careful never to repeat such a grave injustice.

But this message is actually at the very heart of the museum’s existence. The devastating internment of Japanese Americans is brought vividly to life in the powerful permanent exhibition, "Common Ground: The Heart of Community," that includes reconstructed camp barracks, stacks of suitcases, and dozens of historical documents and photographs. Many of the museum's docents spent part of their childhoods in the camps and share memories of their families’ experiences with visitors. Its board members include actor, activist, director and author George Takei, who as a child was interned at the Tule Lake Segregation Center in Newell, California. He has spoken widely about this tragic experience, its impact on himself and the broader Japanese American community. He has also advocated vigorously against the idea of a Muslim registry and President Donald Trump's executive order, which banned individuals from seven majority-Muslim nations from entering the U.S.

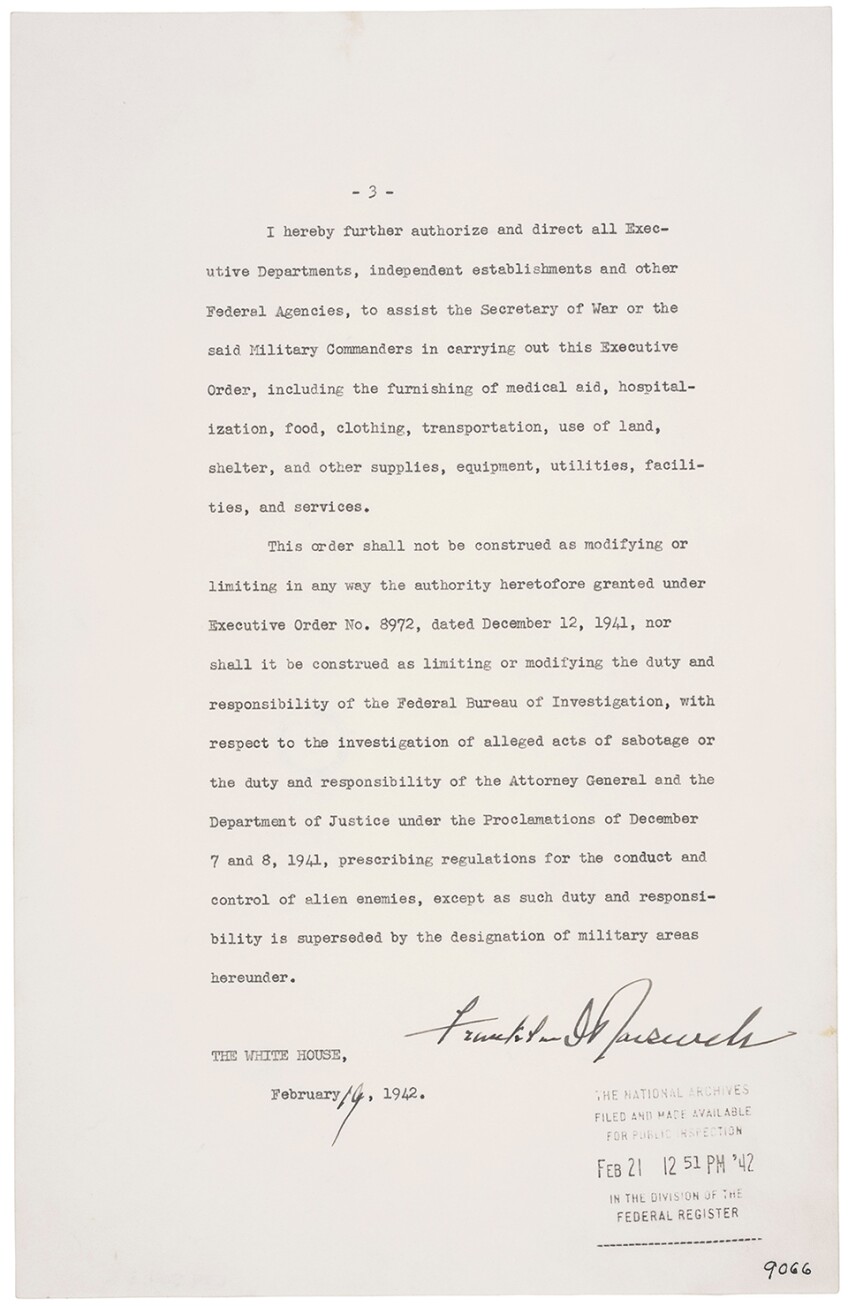

What makes commemorative exhibition "Instructions to All Persons" unique is that it includes the original Executive Order 9066 — the very document that altered the course of so many lives — meaning, it is on view on the West Coast for the first time. On loan from the National Archive until May 21, 2017, the document is unremarkable visually, as would be expected from a government deed — just four sheets of paper bearing typed text and signed in the president’s hand. Yet, its starkness demands a solemn response. Visitors shuffle past the case where it is displayed silently, and perhaps a little fearfully, understanding many decades of its impact. Roughly 120,000 Japanese Americans were incarcerated purely on the basis of “descent,” without any criminal charges. Although two-thirds of these persons were U.S. citizens by birth, the U.S. Constitution failed to protect them, in part because of wartime hysteria, but also because decades of racist attitudes, laws and propaganda suggested that Japanese Americans could never be true citizens. Their experience has taught the whole country how fragile the promise of democracy and liberty can be.

Also on display at the exhibition is Presidential Proclamation 2537, a key precursor to Executive Order 9066 that required individuals from the enemy countries of Germany, Italy and Japan to register with the U.S. Department of Justice, as well as copies of registration forms that these individuals were required to fill out. An entire wall is covered with civilian exclusion order posters of the type that were plastered throughout the Western U.S., as well as photographs of families lining up waiting to be transported to relocation centers, ostensibly for their own protection. Particularly chilling is a newspaper from 1942 that provides a glimpse of how Executive Order 9066 was presented to the broader population.

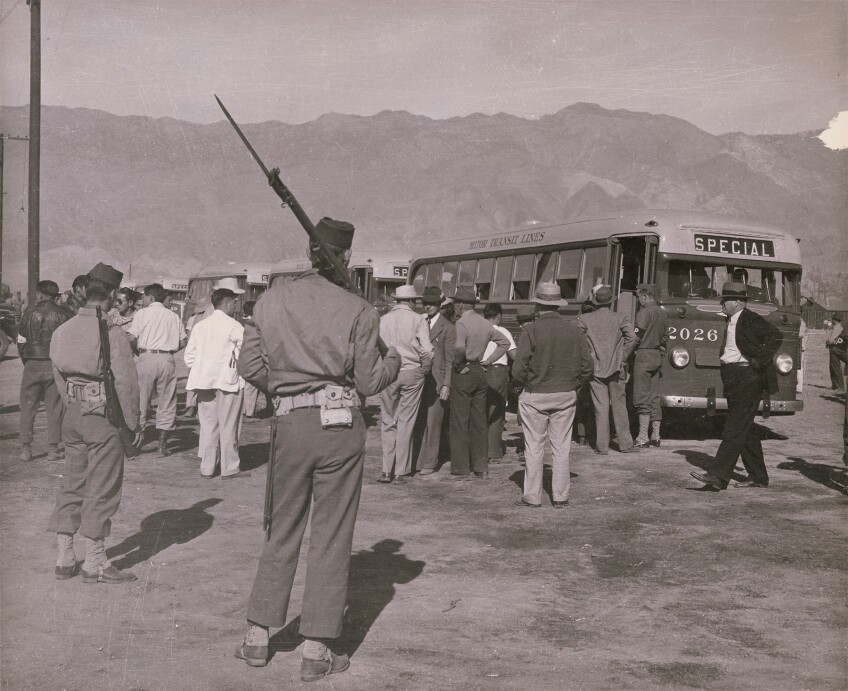

On the front page of the paper is a large photograph of a caravan of cars driving along a freeway. Its caption explains that these are Japanese American families on their way to the “scenic Owens River Valley,” where they will be rehabilitated in a “Little Tokyo in the Mountains.” Portrayed more as an idyllic vacation than an incarceration, this mass movement of people might have seemed less worrying to concerned friends, neighbors and colleagues who watched them leave. In reality, however, once these carloads of Japanese Americans arrived at the Manzanar Relocation Center, the first of the ten detention camps, they were surrounded by barbed wire and guarded by armed soldiers, and later the cars they were transported in were destroyed.

Once in the camps, life was stark, uncomfortable and often humiliating, a fact that is encapsulated by one of the smallest items on display among the documents relating to camp life — the ID tag. Resembling simple luggage tags, these paper tags were worn by the detainees, a reminder of the sub-human status that was assigned to them for the duration of their internment. Japanese American artist Wendy Maruyama captures the degradation inherent in these ID tags in a series of assemblages called "The Tag Project," in which she has mounted between 5,000 and 20,000 replicas of these tags from circular, ceiling-mounted frames, depending on the population of each camp. The three sculptures on display in "Instructions to All Persons" represent Manzanar, Gila River and Heart Mountain relocation centers.

In its 25-year history, the Japanese American National Museum has made it its mission to ensure that the experience of the Japanese Americans is shared with others so that it is never repeated. This exhibition, like many the museum has mounted in past years, explains the destructive effect of fear and racism on an otherwise democratic government. By presenting these valuable documents and organizing them in a thoughtful historical context, the museum successfully demonstrates how easily a government and its people can justify the victimization of a specific community — and how easy it can be for the population to let this happen. At several points in the exhibition, parallels are drawn with the experience, since September 11, 2001, of many Muslim Americans, who have also been victims of mistrust and fear because of their descent. The exhibition text and related exhibition programming warn against allowing this fear to escalate once again and diminish our nation’s humanity. For many decades, many Japanese Americans quietly accepted their treatment, and many of them did not question the government’s action, even refusing to speak of their experiences after the war. It is inspiring now to hear this community raise their voices so loudly in defense of their fellow citizens.

Top image: “No More Japanese Wanted Here” sign in Livingston, California, ca. 1920. | Photo: Courtesy of Japanese American National Museum, gift of the Yamamoto family