John Divola and the Photography of Modern Ruin

"Abandoned houses are one of the few places where you can go and paint anything you want and nobody is going to yell at you," says John Divola.

Divola, whose work is the subject of the multi-venue exhibition "As Far As I Could Get," has taken his camera into a variety of environments over the past four decades. However, it's the vacant, dilapidated home that have been a constant throughout his career. He has found the structures in the San Fernando Valley and in the shadow of Los Angeles International Airport, along the coast at Zuma and deep into the Inland Empire. The modern ruins provided a studio when Divola couldn't afford one. Divola could add to a scene that already existed, perhaps with a few strokes of a paintbrush, and then photograph it. They remain a part of his work, even now that he has his own space amidst the business parks and storage units of Riverside. Ultimately, these venues held an intrigue that went beyond practicality.

"It wasn't a blank canvas," says Divola. "It was something that already had a sense of place and presence and prior activity."

It's the activity that captures Divola's eye. "If someone kicks a hole in the wall," he says, "I'm really interested."

A native of the Los Angeles area, Divola spent the bulk of his formative years in Hidden Hills at a time when the western edge of the San Fernando Valley was far from developed. "I remember when I was a kid, they put in a Thrifty Drug Store on the corner of Topanga and Ventura Blvd," he says. "That was the nearest store. There was a little market in Calabasas, but, other than that, it was a big deal." He took up photography as a student at Chatsworth High School to get out of classes. "I didn't want to be a photographer," he says.

That all changed in the late 1960s, when Divola was an undergrad at California State University Northridge and rekindled his relationship with photography. "I discovered a philosophical way of approaching it that excited me at the juncture," he says. "From the time I got interested, I didn't look back. I was really enamored with it."

"As Far As I Could Get" is a mammoth exhibition, taking place at Santa Barbara Museum of Art, Los Angeles County Museum of Art and Pomona College Museum of Art. It is not a retrospective in the traditional sense. Divola was inspired by an article-- "Navigating John Divola's 1970's Output, And Considerations in Punk and Boredom," by Daniel Shea-- that drew parallels between his early work and punk rock. "I never would have thought of my work as punk because I was a prior generation to punk. That's just not the way I thought of it." he says, "but, I loved it." Divola wanted that sort of outside interpretation of his work to be part of the Santa Barbara and Los Angeles shows and gave the curators the freedom to select works based on perceived themes rather than chronology. In the show catalog, Britt Salvesen, curator for LACMA's Wallis Annenberg Photography Department and the Prints and Drawings Department, writes about existentialism in Divola's work. Meanwhile, Karen Sinsheimer, Curator of Photography for Santa Barbara Museum of Art, delves into the influence of Southern California on the photographs. There are exceptions in the exhibition. Pomona's show centers around his Zuma series. One gallery in Santa Barbara focuses on The Theodore Street Project, a new series.

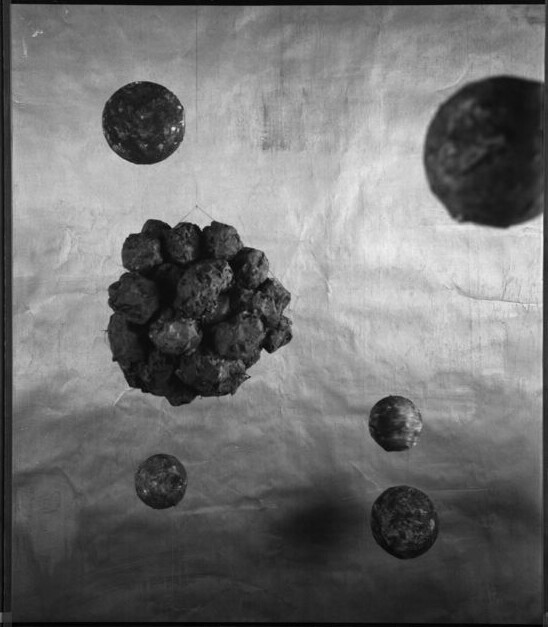

The Theodore Street Project has its roots in Divola's previous work Dark Star, photographs of black circles that he painted inside of abandoned houses. Some time after that endeavor, he returned to one of the houses, a structure on Theodore Street in Moreno Valley. Divola's paintings were still on the walls, but others had added their tags. "Other people painted in a much more sociological manner than I had," he says. He mentions that, in one room, "Kill Whitie" was scrawled on a wall. In another room, someone had left a swastika. "I thought, that's interesting," he says. Divola proceeded to photograph the house using a GigaPan, a device that allows him to take hi-res, panoramic photos piece-by-piece over period of time.The series combines those GigaPan shots with other photos that Divola had taken in and around the space.

Divola does not view his work as political in nature. "It's representational of the sociological present and that cannot avoid but have political implications," he says. However, he adds, "I steadfastly resisted trying to make work that passes judgment on things."

Still, the repeated image of the empty home, found in different parts of the region at different points in time, could point to an ongoing struggle in Southern California.

In the 1970s, his makeshift studios sprouted in the San Fernando Valley, when a recession left many former residences untended. "It was easy to find them," he says. Later, after he moved to Venice, Divola, he documented the disintegration of homes near a growing airport. That became his series, LAX/Noise Abatement Zone. His photos of the Theodore Street house roughly coincides with the most recent recession. However, that's all extraneous information. In the photos, all you know is what is in the frame, maybe some broken windows and torn curtains or rotted pieces of wood and exposed bits of insulation. Anything beyond that is inferred.

Divola says that the definition of superficial should read, "like photography." He means superficial in the most clinical sense, without any negative connotations the word might have. "Literally, you're dealing with the light bouncing off the outside of stuff. Depending on how you contextualize that image, it can mean any number of things," he says. "But, the image, for the most part, is pretty neutral. It's just the light bouncing off something."

For Divola, that neutrality of the image is part of the art. "It is a discipline to actually be able to turn off the internal rhetoric and be able to observe what's in front of you," he says. As a professor at UC Riverside, Divola is concerned with his students' artistic process. "I don't want to know what it's going to be about and I don't want to know what it's going to look like. What I want to know is the process," he says. "I want to know literally how you're going to go about it."

This is a part of Divola's own work too. "It's about observation and engagement," he says. "The process begins to reveal to you the potential of whatever that is. You make decisions and judgements based on the feedback you're getting for it."

Dig this story? Sign up for our newsletter to get unique arts & culture stories and videos from across Southern California in your inbox. Also, follow Artbound on Facebook and Twitter.