LAPD 1994: Portraits of a City in Pain

The following is an excerpt of an introductory essay to Joseph Rodriguez’s “LAPD 1994.”

I’m writing this in the dead of Pandemic Summer 2020, also the Summer of Black Lives Matter, to give some context for my dear friend Joseph Rodriguez’s photographs from another moment that tore open the soul of America.

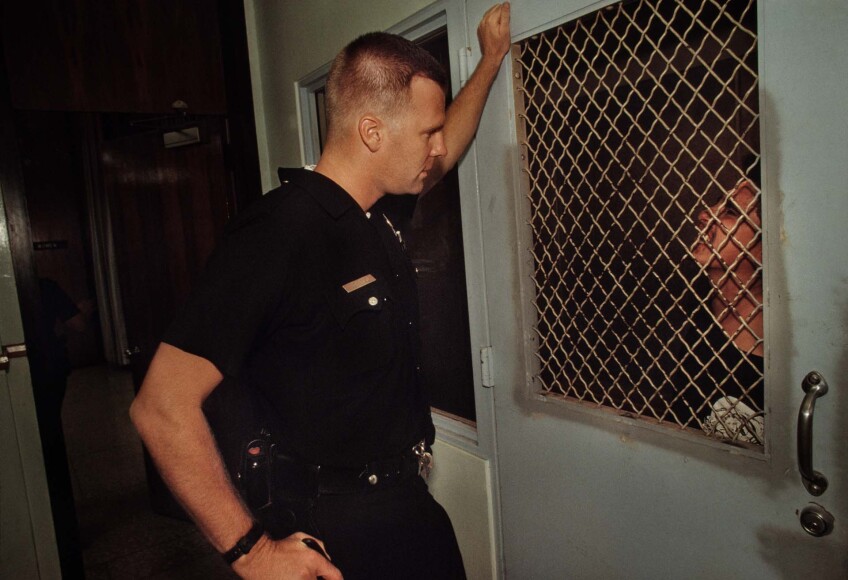

Joseph’s decision to collect his New York Times Magazine ride-along shots and produce this book is a deeply personal, political act. The photos display his subjectivity — sketched out by Lauren Lee White in her foreword — as much as that of the cops and the civilians. Those civilians, victims and sometimes perpetrators of violence, often are the target of the cops’ casual inhumanity — or worse. It is a portrait of a city in pain.

“LAPD 1994” joins a body of work representing the city of Los Angeles to itself, its images part of a movement of creative self-expression among working class communities of color that had many precursors but crystallized in the 1990s — the moment in which South Central and East L.A., queer L.A., even homeless L.A. started telling their own stories.

Immersing you in the 1990s is essential because photography, after all, is about time — the moment the frame captures and the past and future it alludes to. It also is about place. Joseph’s images produce an overwhelming sense-memory for me: I survived and, honestly, thrived in that time and in that place, Nuestra Señora la Reina de Los Ángeles de Porciúncula.

The ’90s prologue has its own prologues. You can keep going back in time, 2011, 1992, 1965-68, 1943, all years of major uprisings in America. For the deepest antecedents, you can go all the way to independence and the contradicted pronouncements of the Founding Fathers. “Uprising” might not be the perfect descriptor, but unlike the reactionary “race riot,” at least it affords a clear agency to the subjected bodies that collectively say “basta” and rise up with what Malcolm X called “intelligence” to defend their lives and dignity.

The old L.A. WASP power structure began crumbling with the decadent mayoralty of Sam Yorty (1961-1973), an overtly racist buffoon. Then a Black-Jewish alliance ushered in an era of mild reformism with the 1973 election of Tom Bradley, the city’s first African American mayor, whose two decades in power were shrouded by the 1992 uprising. Latinos in Los Angeles began emerging in the power structure on the heels of African Americans. Among other breakthroughs, the Eastside in 1991 elected a Chicana, Gloria Molina, to the tremendously powerful County Board of Supervisors.

Policing has long been at the center of American urban political struggle — law and order for conservatives, reigning in excessive force for liberals, a binary blown open recently with the new movement to abolish/defund the police.

Click right and left to see a few of Rodriguez's powerful photographs:

But change at the LAPD over time was more symbolic than substantive. Mayor Bradley, himself an LAPD veteran, seemed well-positioned to transform the department. Instead, it became the last bulwark of the old order, anchored by the downtown business and media elites, impervious to demographic change and labor and civil rights.

Starting in the mid-1980s, L.A. added multiculturalism and its location on the Pacific Rim to its longstanding “city of the future” motif in a bid for global status. City Hall’s timid centrism and the Reagan-Bush era of tightened budgets, however, darkened prospects citywide, but especially in Black and Brown L.A. All the while, frustration was building in East L.A. and South Central’s housing projects, where branding as gangsta territory served both the LAPD’s paramilitary containment designs and the claim to authenticity of o.g. rappers like N.W.A. The frustration percolated in the immigrant tenements of Pico-Union, in the rust belt shadow of stilled factories, among the ever-growing homeless population downtown.

But unless you were the subject of the frustration you couldn’t see it easily. The city’s geography and infrastructure worked against visibility, with segregated expanses demarcated by freeways, an enhancement of redlining. The media — for the better part of the 20th century hegemonized by a conservative, viciously open-shop Los Angeles Times — encouraged ideological blindness by simply ignoring the “other” or rendering it utterly savage, providing the LAPD a justification for generations of repression and allowing it to play the brute role of “enforcer” of the structure.

It took two of the biggest uprisings in American history to begin the ongoing change of policing in Los Angeles.

1965, 1992.

I was alive in ’65 but, unlike my Mexican American father, not yet aware of the world he had to see as he drove to his job at a print shop through smoke and sirens and a “wilderness of smashed plate glass,” as James Baldwin wrote about Harlem two decades earlier. The Watts Rebellion ignited when brothers Marquette and Ronald Frye and their mother, Rena Price, made a stand not against a singular arrest for suspected drunk driving, as was reported at the time, but against an almost all-white police force that turned race and poverty themselves into crimes. The cop’s preferred tactic was to use innocuous infractions like broken tail lights or jaywalking as opportunities for them to set potentially lethal examples of social control. The Watts uprising lasted six days and took 14,000 national guard troops to quell.

I was around for ’92, a young reporter for public television and the L.A. Weekly, the city’s alternative paper, and was among a handful of professional journalists of color working in the city. On April 29, the jury in the practically all-white cop bedroom community of Simi Valley (a reward the defense received for its change-of-venue request) handed down not-guilty verdicts in the case against four LAPD officers caught on videotape mercilessly beating a harmless Rodney King.

Armed with a then-cutting edge pager and my notepad, I ran from one spontaneous demonstration to the next. From First A.M.E. Church where the Black establishment pleaded in vain for peace, to LAPD headquarters downtown where a multiethnic crew of young people — presaging today’s George Floyd coalition — torched patrol cars and nearly overran the terrified cops tasked with securing the building, to the old Los Angeles Times headquarters on Spring Street, damaged but not destroyed, that the activists considered a legitimate target.

I watched and documented as the city, burning and writhing for five days, gained global fame — the very opposite of the image its elites had sought.

In 1965 and again in 1992, blue-ribbon commissions produced the best critiques on the origins of the uprisings and reform agendas that the liberal order could muster. These exercises were in vain. Or cynical. The fact that the biggest scandal in LAPD history took place in the Rampart Division six years after the 1992 uprising, and a few years after Joseph’s magazine assignment, tells that story.

It’s not that nothing has changed. What was transformed, by a momentum building steadily from below long before the riots, was the cultural means of production. Ordinary Angelenos without talent agents or gallery or industry connections took artistic authority into their own hands and reflected the city back to itself.

The rappers of South Central, first and foremost. At the Belmont Tunnel, the city’s premier graffiti yard in the shadow of the glass and steel towers of the new downtown, working-class white kids battled Chicanos, developing an aesthetic that diverged significantly from New York’s wild style. Immigrant youth from Mexico and Central America, some trilingual in English, Spanish and Indigenous languages, picked up the echoes of the L.A. punk scene of the late 1970s and early 1980s and concocted a syncretized sound — “rock en español” — that was as grungy as it was sweetly reminiscent of their homelands.

At Highways Performance Space in Santa Monica, a crew anchored by queer performance artists uproariously explored every iteration of otherness. Black poet Wanda Coleman, the city’s unofficial bard who should have been official, composed her shattered love poems to the city from “behind crack-broken backs and tickled palms/in hallways dark.” Even homeless Los Angeles took to the stage to represent itself: The LAPD (Los Angeles Poverty Department) theater troupe, one of the most radical art experiments of its time, blasted open the fourth wall to turn the stage into the street itself.

Gradually, some of this energy bubbled up into the mainstream. There was post-N.W.A. Ice Cube setting down his AK on “It Was a Good Day,” and Tupac living and dying in L.A. to a classic, laidback, SoCal R&B vibe, recorded just weeks before his fateful trip to Las Vegas. The decade began with John Singleton’s astonishing 1991 debut feature “Boyz n the Hood,” as honest and sympathetic a representation of South Central as there’s been before or since, a meditation on self-destruction and resilience in LAPD-occupied territory. A few years later, Mexican American director Gregory Nava brought a poignant, healing gaze to the trauma that accumulates across generations in “Mi Familia,” which uniquely braided Chicano and Central American narratives as these two haunted communities began merging in the city as a result of the civil wars in El Salvador and Guatemala. As the son of a Mexican American and a Salvadoran, I can attest to the dearth, even today, of such storylines.

But perhaps the ultimate masterpiece was the representation of the 1992 uprising itself, captured on then-widely available personal videocams and by local news footage on the ground and from “newscopters.” The flashpoint, after all, wasn’t in Simi Valley or the “ground zero” of violence at Florence and Normandie in South Central, but in Sylmar, where George Holliday trained his brand-new Sony Video8 Handycam on LAPD officers nearly lynching Rodney King, seeing what was not supposed to be seen. Collected in several recent documentaries on the 20th and 25th anniversaries, the images comprise a radical, point-of-view experiment: white gazing upon Black, Black upon white, Korean on Latino and Black, rich upon poor, and helicopter shots approximating a “Bladerunner” view from suburban “off-world colonies.”

The ‘90s did not keep Los Angeles on a linear course toward cultural revolution. The decade also spawned the inevitable reaction, the old order with new packaging — development as gentrification, rampant speculation dressed in hipster style and nominal progressivism. As rents skyrocketed, the homeless population exploded, and the reversal of white flight sent communities of color fleeing to the relative affordability of the suburbs and exurbs.

In the midst of today’s Pandemic Summer, Los Angeles once again has risen up from below to be seen, joining the Summer of BLM, which has spawned reckonings in newsrooms across the country over their complicity in systemic racism. Meanwhile, efforts at revealing hidden figures, like the New York Times’ 1619 Project and the Los Angeles Times’ passionate commemoration of the Chicano Moratorium on its 50th anniversary, among many others, are building upon successive generations of writers and artists who’ve been telling our stories all along.

Joseph frames pain in these images, but bringing the darkness to light is also a sign of hope. As we see ourselves more fully, we are more fully seen.

Author's Notes:

- For a profoundly moving theatrical immersion into King’s uniquely L.A. backstory, see Roger Guenveur Smith’s “Rodney King,” a one-man show filmed and directed by Spike Lee.

- The scandals did not end with Rampart. There have been dozens of questionable officer-involved shootings and high-profile scandals of excessive force, like the May Day Rally of 2007 in MacArthur Park where, along with the usual rain of batons and rubber bullets, motorcycle cops rammed protesters with their bikes. Flash forward to the George Floyd mobilizations of June 2020, in which activists allege the LAPD responded with SUVs charging activists, transphobic abuse and more, much of it caught on cellphone video. As this book was going to press, a new major scandal involving members of the elite Metro division framing Black and brown men as gangsters resulted in the DA dismissing several felony cases.

- Poetry from Wanda Coleman was from “American Sonnet: 91” from her Mercurochrome collection, published by Black Sparrow Press in 2001. The full poem is available to read here.

View a virtual exhibition of these photographs produced by Bronx Documentary Center from February 5 to March 26.

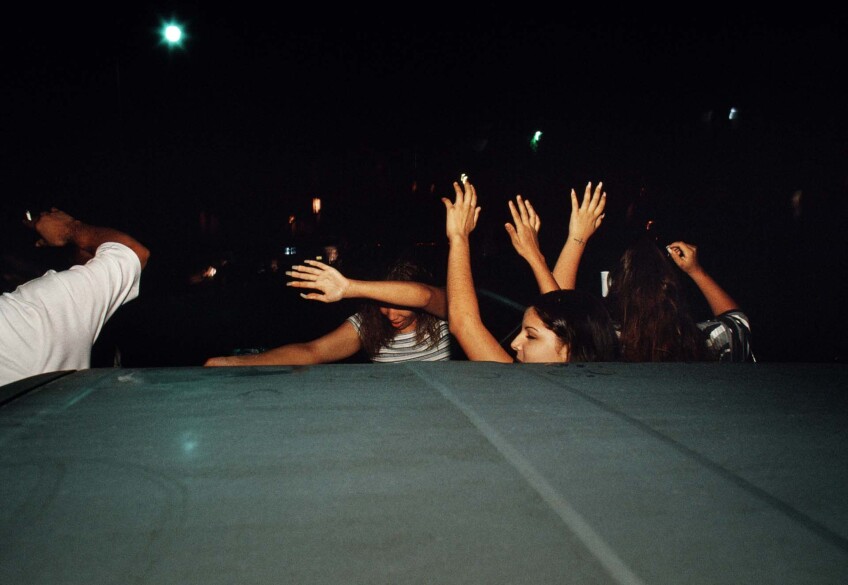

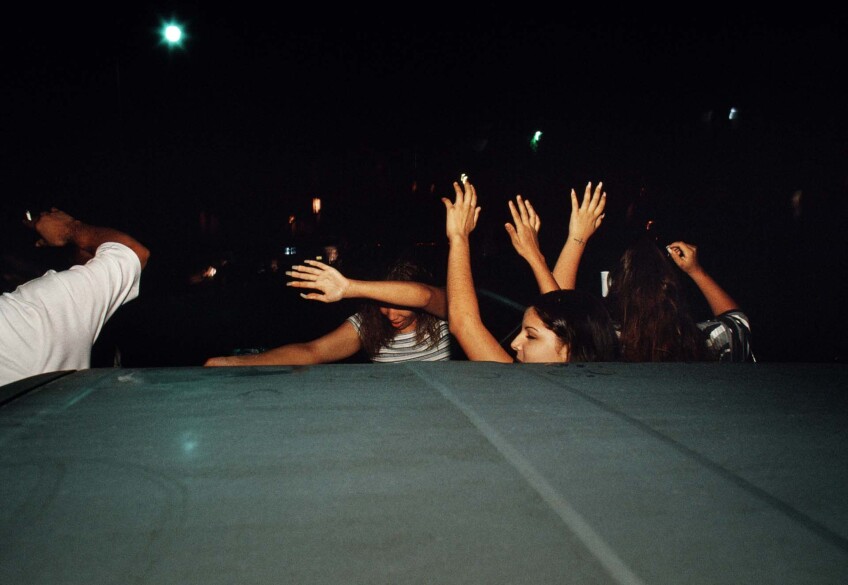

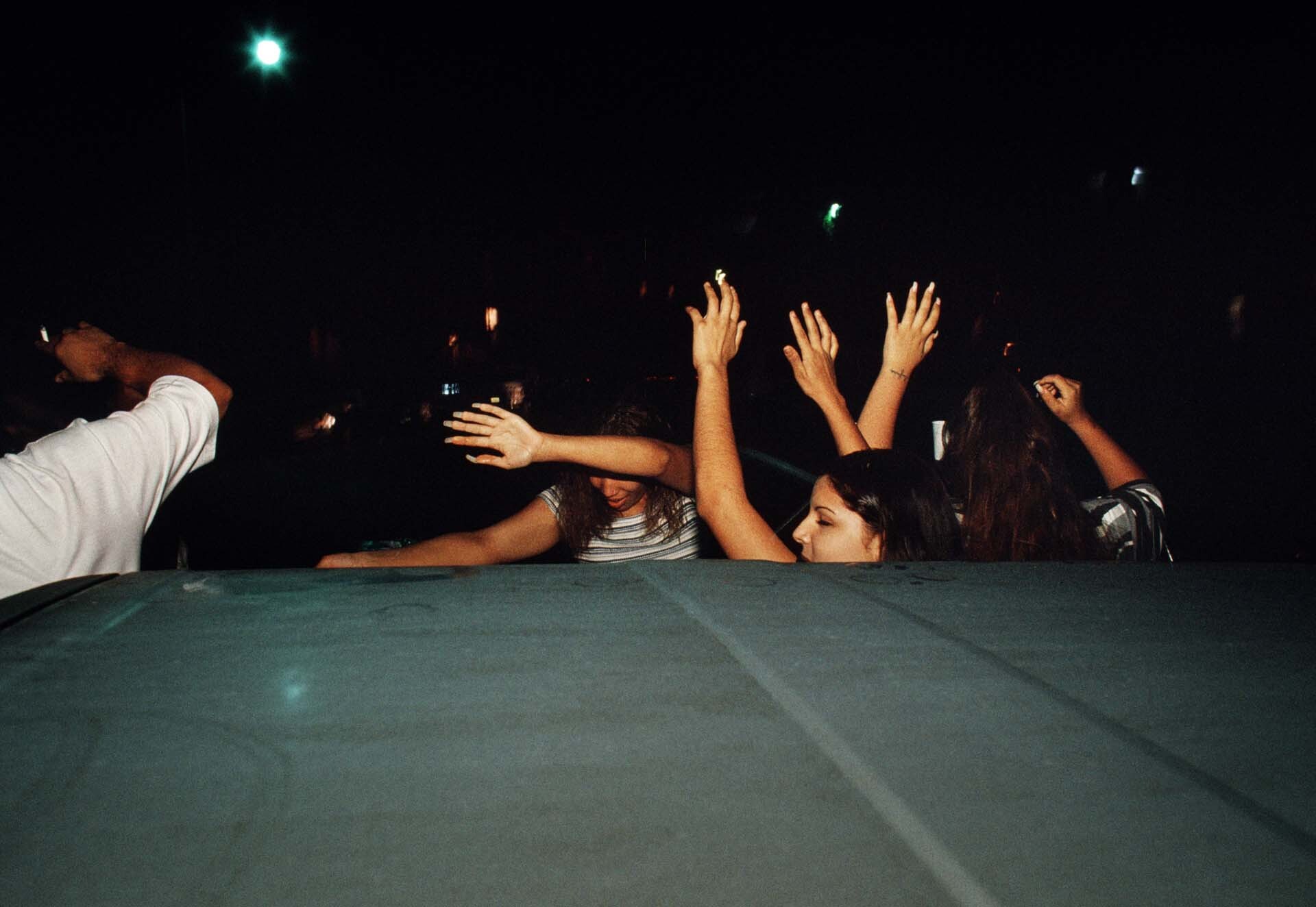

Top Image: In Pico-Union, officers follow up on a house party noise complaint someone has called in. | Joseph Rodriguez