Listening to the Male Gaze: Voice Politics in the Videos of Adebukola Bodunrin

“Hear My Voice” is a clean, elegant, ironic and disturbing meta-rendering of the cliché that women should be seen and not heard. In the videos, a streaming mass of diverse women whose faces, mouths in motion, flash in succession. The women’s voices go unheard as one witnesses their lips and cheeks forming silent phonemes. Meanwhile, anonymous women provide serialized voiceovers. In succession, they read misogynist comments about feminine linguistic styles. The comments provide chronological and thematic structure for the short video, and each one yields prototypical aural criticisms that many women are sick of hearing. While the first comment condemns women for committing the high crime known as vocal fry (“a low staccato vibration during speech”), the last bit of snark frames feminine linguistic patterns as naïve, childlike, and irresponsible: “I know you’re easily offended now but you’re just young which is something we all get over eventually. Just keep repeating: I can learn to speak like an adult. Love y’all.”

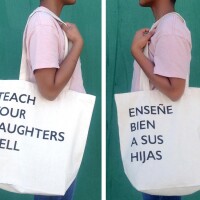

Made by Adebukola “Buki” Bondunrin, a film, video, and installation artist, the project was commissioned by Freewaves, a Los Angeles based non-profit that nurtures independent media. The video would be part of the organization’s DIS…MISS project, a public visual art experience centering on perceptions and attitudes towards gender.

Though she sits outdoors, Bondunrin is employing her indoor voice. An ivy canopy shades her but the rhinestones encrusting her gold rim glasses sparkle. They especially twinkle as she tells the story of how two strangers, one a woman, the other a man, tried talking their way into her artwork. Bondunrin was shooting footage for this video at Leimert Park’s KAOS café when the aforementioned strangers strolled in.

Posters calling for female volunteers, which Bondunrin had stuck to the building had intrigued the pair, drawing them indoors, and the woman gushed to Bondunrin that she couldn’t wait to be filmed, insisting, “I’ll totally pose for you! I can’t wait!” The woman’s enthusiasm charmed Bondunrin and so she relayed her artistic vision to her model-to-be. She told the woman that she was producing an art video exploring voice politics, specifically attacks against feminine linguistic styles. After the artist articulated her vision, the male stranger proceeded to justify the project. “He took over the space with his voice for about ten minutes,” says Bondunrin. She described the verbal manspreading episode as a colonization executed through volume and logorrhea.

“It was so weird,” muses Bondunrin. His loquacity did seem well intentioned. He kept hyping his female companion, asserting that she was “the most amazing woman on the planet.” Bondunrin drawls, “I was like, ‘Hey man, that’s cool, but I’m not that interested in what you have to say.’”

She chuckles. The allegory, or malegory, speaks to the necessity of her work, to how quickly and easily women are denied the power to represent themselves. Female subjectivity and agency interest Bondunrin, not male stewardship or surrogacy of the female voice, which is not to say that Bondunrin has no interest in men’s voices. Men’s voices lurk in her work but in Hear My Voice they function instrumentally, as props used to expose male aurality, the auditory analog of the male gaze.

The female stranger did make it into the final cut of “Hear My Voice,” Bondunrin’s DIS…MISS video. It will be shown August 4 at KAOS Network and August 5 at Self Help Graphics.

Childhood experience stokes Bondunrin’s interest in voice. Born in Nigeria, she largely grew up in Toronto, which she describes as “very cosmopolitan and multi-cultural.” As an immigrant kid in Canada, she moved through communities inflected by myriad, international accents. As a kid, she also experienced a speech impediment, a stutter accompanied by difficulty producing S, T, and R sounds, and so, beginning in second grade, Bondunrin worked on her voice. At school, she would skip physical education to meet with her speech therapist. For two years, this therapist trained her, teaching her to pronounce vexing phonemes and leaching the staccato from her speech. The therapeutic experience, which Bondunrin describes as a form of sound policing, sensitized her to notions of verbal coherence and voice politics. Her video “It’s Hard to Recognize Speech” reenacts these childhood ordeals and her subsequent sociolinguistic epiphanies.

Bondunrin’s experiences with teaching and on social media inspired the video. While teaching animation and graphics to students not much younger than herself, Bondunrin noticed that she was struggling to sound authoritative. She had a particularly tough time getting her male students to take her seriously and so she found herself doing a lot of “performative things” with her voice. This self-policing of how she sounded felt familiar, an extension of speech therapy, and she pondered that. Also, around the time that Freewaves commissioned her video work, Bondunrin heard a female podcaster discuss the hate mail she receives. None of it had anything to do with the content of her speech. All of it had to do with her voice. Bondunrin argues that this concern with how women sound is a false complaint. Most complainants don’t want women to change how they sound. They simply want women to be silent.

Bondunrin scoured the internet, harvesting complaints about women’s speech and choosing favorites. She kept these comments with her and when hearing interesting women’s voices in public, she’d approach the speaker, explain her project and ask if she could record the woman reading one of the comments aloud. Not only were those who she asked glad to oblige, every woman also told Bondunrin a story of being personally silenced. These women treated the offer to participate in Hear My Voice with retaliatory enthusiasm.

While President Trump is working hard to keep the practice of female body shaming alive, the public’s general tolerance for such behavior is in decline. As a result, misogyny has had to innovate. Instead of focusing on a corporeal mark, hatred of women is now aimed at the disembodied feminine. “As the paradigm shifts,” says Bondunrin, “the target shifts to the voice.” In terms of voices that shape her work, Bondunrin cites African-American feminists Kara Walker, Octavia Butler and bell hooks. This month, the New Yorker published an essay by Abby Aguirre arguing that Butler’s “Parable of the Sower” and its sequel are “unmatched” for the “sheer peculiar prescience” they demonstrate in light of our current political crisis. Butler’s work also provides a compass for decoding Bondunrin’s work. In Butler’s science fiction short story “Speech Sounds,” an aphasic illness has robbed southern Californians of verbal communication skills. The story’s protagonist, a woman, continues to insist on speaking. She not only declares her name, Valerie Rye, but “[savors] the words,” telling the children of dystopian California, “It’s all right for you to talk to me.” This is the message being conveyed by Hear My Voice: You may speak. The sound of your voice sows hope.

Top Image: Microphone | Adam Fredie/Flickr/Creative Commons