Ryan Hester: PHREEdom and Frenzy

Modern racism, both institutional and social, continues to fester at the heart of a country that is often combating its own people. Racially motivated violence against blacks endures as the prototypical hate crime, recalling and perpetuating a catastrophic history of lynching, slavery, and police brutality. The tragic loss of innocent lives is staggering, with the most recent being those taken at the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, South Carolina. Propagating a form of activism through his own artistic endeavors, Inland Empire-based artist Ryan Hester, also known by his artist pseudonym PHREE, reconstructs fragmented imagery to create a language all his own.

Hester, 24, is native to the Inland Empire and frequently moved between Los Angeles and San Bernardino County throughout his youth. Heavily inspired by the landscape of both cities, Hester found inspiration in the graffiti and street art that saturated both urban settings. "Seeing the graffiti just kept everything going," Hester says, "Also being in the environment of San Bernardino and the circumstances that make it that way." Initially creating strictly illustrative works, Hester gradually moved into painting about 4 years ago, developing his style through sharp gestural qualities indicative of street art while employing techniques such as Surrealist automatism. On his own relationship with Surrealism and surrealist techniques, Hester notes that "even before I knew about art, I knew about Dali."

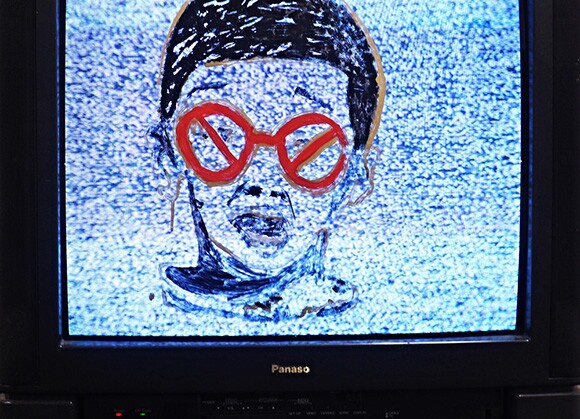

Through a vibrant fusion of loose painterly expressionism and charged icons, Hester's work functions threefold through a seamless fusion of semiotics, pop art graphics and graffiti. "It's kind of like pop art throw-up, where it's not pop art, but it kind of is," Hester says. "People think it's simple, but it's a lot more complex than just putting things together." The political provocation within many of his works reiterates the heaving breath of racial and social angst in American culture and the violence that so often accompanies it. Hester's flat and frequently chaotic style saturates his work with an electric and playfully elusive sensibility. The frenzied bold lines and heavy smears of paint have an undeniable presence similar to that of Basquiat; an understatedness that's equally dynamic and seductive. Other nods to the late artist found within Hester's paintings include Basquiat's early use of the three-point crown, which occasionally accompany his subjects.

Many of Hester's works, it would seem, revolve around power and the powerless, paralleling the pervasive dynamics that could continue to drive our world into an increasingly bleak future. Hester's subjects float adrift in a distorted and jumbled sea of iconography. With a strong sense of personal activism, the flatness of Hester's subject matter lays bare a candid sensibility, perhaps driven by his own experiences of being black in America where violence against African Americans is still dishearteningly common. One of Hester's more politically charged works, "New Slave," 2014 clearly outlines not only black subjugation in a white-dominated society through the use of a literal slave driver, but remains indicative of Jim Crow laws and the eroticization of the black female body. The subject's partial lines and worn appearance seem symbolic of her incongruous and disjointed position within society. The words "New Slave" painted in the upper, left-hand corner drive this point further by hovering over the subject as a satirical yet crudely accurate logo. A similar, yet subtler work, "Artist and the Muse," 2013 parallels these themes through the quiet use of a partially hidden face and stark, jagged eyes. Hester's gently implied malevolence through the subject's bulging and anxious glare reverberates with fear as she disappears into the brick and mortar.

Outside of his work's social commentary, many of Hester's paintings are rich in their smaller moments as well. Hester's loose, heavily gestural style catapults his work's themes even beyond issues of race and into the larger, more complicated realm of capitalism and economic privilege. More humorous paintings, such as the tongue-in-cheek "The Struggle is Real," 2015 presents a witty and complex presentation of class adversities and individual empowerment.

The interlocking socio-political structural foundation of an inherently imperialist white-supremacist capitalist country consistently finds itself at the helm of Hester's work. Amid bodies and ruin, fragment and chaos, there is a prolific reclaim of power. With an alluring and sometimes disorienting amount of visual information, Hester's appetite for analogously symbolic imagery expands his personal lexicon beyond the social and political factors inherent within his work. With an impressive and broad array of work that routinely defies commodity, Hester's biting wit lays bare and probes the commodification of black culture while simultaneously confronting social identity and violence against blacks.

Dig this story? Sign up for our newsletter to get unique arts & culture stories and videos from across Southern California in your inbox. Also, follow Artbound on Facebook and Twitter.