Soap Plant + WACKO Turns 50: A Look Back at Its Underground Art Scene and Legendary Parties

A neon sign emblazoned with the word "WACKO" adorns a longstanding institution along Hollywood Boulevard in Los Feliz. It's a colorful, 6,500-square-foot complex that houses Soap Plant, WACKO and La Luz de Jesus Gallery — a pop-culture toy and gift shop and exhibition space that have been a part of the fabric of Los Angeles since 1971.

Soap Plant, Inc.'s 50-year history is a storied one, from its humble beginnings as a family-run soap shop, to its evolution into a vibrant gallery space that propelled California's lowbrow art movement into popularity. In the 1980s and 1990s, the gallery hosted wildly popular underground art exhibitions, which were curated by Robert Lopez (who performs under the stage name El Vez). The raucous and subversive art openings attracted the likes of Guns N' Roses and Andy Warhol.

On a deeper level, WACKO also holds a special place in the hearts of former employees. The store became a home away from home for artists and musicians who sporadically moonlighted as the shop's staff over the years.

A Family Affair

William "Billy" Shire was 20 when he launched the original Soap Plant location with his mother Barbara Shire in the early '70s. It was located in the Sanborn Junction, a mixed neighborhood that he described as queer-friendly and "hip before the hipsters" at the time.

It was a place for Barbara Shire to sell her handmade soaps and keep busy during her empty-nest years. Before opening the store, she was active in her community and leaned toward left-wing politics. Billy Shire remembered his mother was involved with Women's Strike for Peace and the Citizens Committee to Save Elysian Park.

"I would be sitting at the table doing my homework, while the Communist Club was meeting in my house," Shire recalled in a 2014 Los Feliz Ledger obituary on his mother, who died at the age of 100.

Shire had a workshop in the back of the store, where he did leatherwork. The self-taught leatherworker attracted the attention of rock-and-roll costume designer Bill Whitten, who famously created Michael Jackson's white sequined glove. Whitten enlisted Shire's help to work on concert costumes for the likes of Elton John and The New York Dolls.

In 1974, Shire created a studded denim jacket for a Levi Strauss-sponsored design competition. He won. It altered the course of his life, but not in the way he anticipated. "I thought I was going to be a really famous belt-maker, but I got absolutely no business from that, so I ended up re-evaluating this store for a year," Shire, who's now 70, told KCET. "I've been doing it ever since."

The Birth of WACKO

In Soap Plant's early years, Barbara Shire enjoyed running the store and chatting with customers. But after she became sick and less involved with the shop, Billy Shire took over the business as the sole owner in the early 1980s. He relocated Soap Plant to Melrose Avenue.

It became much more than a soap store at this point. Shire sold imported toys, books, ceramics, clothing and tchotchkes. He expanded his business in 1984 by leasing some extra space next to Soap Plant. That extension became WACKO.

"My main emphasis in the stores was pop-culture from Europe, Japan and Asia," Shire said. "When China first started opening up, I was bringing in all the tin toys and all the basketry and anything I could get."

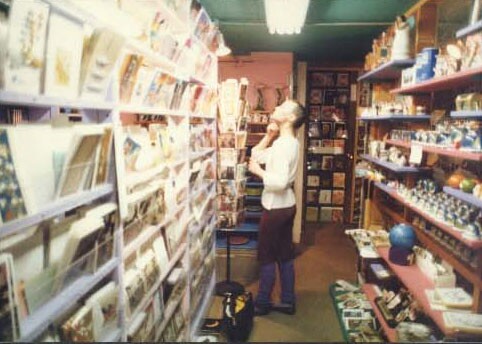

Nowadays, WACKO doesn't sell much soap, but its inventory has grown exponentially. The store is now home to over 10,000 items and art pieces. Godzilla figurines, tongue-in-cheek occult books and plush Japanese dolls line the shelves of the megastore, a place where you can easily get lost in for hours.

Shire hasn't strayed far from his roots in running his business. "I come from a very socialist-communist background and I've tried to make my store very hospitable and inexpensive to everybody, and I treat my employees right," he said.

La Luz de Jesus Gallery and the Lowbrow Art Movement

Shire began taking trips to Mexico in the mid-1970s and fell in love with the country. He collected Day of the Dead artwork and brought the pieces back with him stateside. Lopez, who at the time was in legendary punk band The Zeros and simultaneously a WACKO employee, was similarly importing Mexican folk art in his spare time. The two friends and colleagues found a common bond in the arts.

"We would go to Mexico, weeks at a time, and collect Day of the Dead stuff and ship it back to Los Angeles, and meet with the artists and make special requests," said Lopez, who's now 61. "So we spent a lot of time together, hanging around Mexico City or other cities. We knew each other's art and history senses."

In the mid-1980s, they decided to host their first exhibition showcasing their Day of the Dead collection. At the urging of Lopez, Shire kept the shows going. In 1986, he opened La Luz de Jesus Gallery upstairs above WACKO.

Lopez became the gallery director, curating monthly exhibitions. He remained in that position for nearly a decade into the early 1990s. The shows were folk art-oriented, underground and subversive. La Luz showcased some of the earliest exhibitions from artists like Robert Williams (founder of Juxtapoz Magazine) and Gary Panter (a cartoonist and painter who famously created set designs for "Pee-wee's Playhouse"). It contributed to the California lowbrow art movement, Kustom Kulture and pop surrealism.

"California was basically the center of pop-culture in the world in the second half of the 20th century," Shire said. "Surfing, hot-rodding, tattooing, pinup … came out in California. And that is basically what I've settled the store on, plus, bringing in the pop culture of the world. To an extent, it is my art piece, my life's labor."

Lopez's cousin, Michel Chenelle, who started working at WACKO in 1985 and later became La Luz's curator in the early aughts, called the gallery the "next iteration of punk rock."

"A lot of people in punk rock were underground artists," Chenelle, 61, explained. "Once the music had kind of been appropriated, they said, 'I'm going to go back to my art roots,' and they started to create art. And what was fun is that Robert [Lopez], because he had a connection to the punk rock world being in The Zeros — the very first generation of punk rockers in Los Angeles — he was able to pull a lot of these people to the art gallery."

Lopez recalled that one of the best parts about La Luz was its themed art openings that were filled with performance art. There would be musicians, drag queens and singers. It became a scene. Lines to get in snaked around the block. Celebrities popped in.

"While working at this great place, one moment Axl Rose could come in, or Andy Warhol or John Waters or Michael Jackson," said Lopez.

Chenelle remembered that for an Elvis Presley-themed show, they served fried peanut butter and banana sandwiches, in honor of the late singer's favorite food. At a gospel night, punk rockers dressed in robes belting out gospel songs.

"There was always something really crazy to do when Robert [Lopez] was a curator, and so he always dragged me in and I would be like go-go dancing [dressed] in Guatemalan cloth," Chenelle said.

Lopez had a knack for creating the shows' atmosphere through performances, like when he hosted an exhibition for Williams' controversial art. At the time, critics complained that Williams, a painter and cartoonist who created the cover art for Guns N' Roses' "Appetite for Destruction," made sexist art that objectified women. In response, Lopez had Chenelle pretend she was a feminist magazine reporter at the opening.

"I'd go around and point out how sexist the art was, and take on Robert Williams, and be like, 'Don't you know this stuff is sexist?'" Chenelle said.

At another Williams' show, Lopez built a boxing ring in the gallery as a companion piece to his work. "We had employees act and do foxy boxing, but putting a feminist take on it and making it strong and commenting on both sides …," Lopez said. "But just the idea of building a boxing ring into the gallery for the art opening was pretty ridiculous and funny."

Chenelle was one of the women who donned silk lingerie and boxing gloves, and duked it out in the ring. She remembered MTV was there filming it.

"I think that's how the gallery got such a reputation for the first Friday nights of the month," Chenelle said. "You've got to be at the La Luz gallery, because if you don't like the art, something else is going to be happening — and it's going to be amazing."

Moving On at La Luz

Performance art bled into real life. When Lopez curated the Elvis Presley-themed art show, he also performed as El Vez, the Mexican Elvis. It took off.

"Being the curator and also being in charge of PR, it was where I turned all this knowledge onto myself," Lopez explained. "And it just kind of snowballed, the idea of being living art myself, as the performance of El Vez, the Mexican Elvis."

Lopez said it was great performing as El Vez while running La Luz. Camera crews from MTV and Entertainment Weekly would film him promoting the gallery in character. Eventually, he left his curating job to do El Vez full-time.

In 1995, Shire moved WACKO and La Luz to its current home in Los Feliz. There were a few curators in between Lopez and Chenelle, who took over as gallery director from 2001 to 2004. She brought in artists like Shag (a.k.a. Josh Agle) and Glenn Barr.

"It was interesting because when they first started with Robert [Lopez], the fine art world was pretty well-coated, like there were certain things you could do and certain things you wouldn't do," Chenelle said.

She credited La Luz for giving underground illustrators and comic book artists a chance. However, the art scene had evolved over the decade after Lopez left. Shire noted that "everything's changed" now with the growth of the internet and the sheer number of artists and galleries out there.

"By the time I came around, it almost seems like a lot of that stuff was old," Chenelle said. "What could you do that hadn't already been done? But it was interesting because we got a lot of people who were raised in this new underground art, deviant art or lowbrow art world. They were going to school to do lowbrow art, and you were getting an interesting new branch of art that came out."

A Second Home for Creatives

WACKO wasn't just a special spot because of its art scene. It was also a place for artists, musicians and actors to always call home. Shire offered creatives jobs at his store, and was flexible about letting his employees come to work in between their own passion projects. About 40-45 people would work at the store at a time.

"Billy, being the mother hen, allowed us the time to take off, or promote or come to the shows," Lopez said. "You could put a poster [of your show] in the window. It was such a bed of creativity…"

Lopez recalled how creative projects could easily percolate in the store because of the great amount of artistic talent pulsating through the store. If someone needed a guitarist, a person downstairs could fill in. They used WACKO as a rehearsal space.

Chenelle also had a chance to work at WACKO between projects and travels. "I think that's one of the interesting things about Soap Plant, that it was a touchstone for a lot of people to kind of go out," she said. "And then they always knew that there was a place for them to come back to, like when things didn't work out or their adventures were over."

She's now a middle school teacher in Northern California, but still helps Shire get in contact with former staff for reunions. Chenelle helped out with WACKO's 40th anniversary reunion, in which Shire said over 400-500 people showed up, about 90% of his past employees. They were planning on doing a 50th year reunion on their anniversary on Juneteenth, but because of the pandemic, they are rescheduling it to next year.

"A lot of people think of it as their high school reunion [with] the family they never had," Chenelle explained. "It's definitely a huge thing in the lives of a lot of people who worked there."

Shire called it "punk rock college." It's special to him, too. "They're kind of like my kids, because I didn't have kids," he said. "I feel like I brought up teenagers and 20-somethings."