Soldadera: Memory Machine

Inspired by Nao Bustamante's exhibition, Soldadera -- the artist's "speculative reenactment" of women's participation on the front lines of The Mexican Revolution -- Artbound is publishing articles about the exhibition's development, historical contexts engaged by this project, and writing inspired by the work. Soldadera was guest curated for the Vincent Price Art Museum by UC Riverside professor Jennifer Doyle, and is on view from May 16 - August 1, 2015.

Smells, like memory, are interpretive. A familiar, comforting scent for one person can be a traumatic reminder for another. In this way, our sense of smell can serve as a vehicle to travel through time. Memory, similarly, is flexible and subject to changing interpretations over time. We can reshape how we remember a past experience to suit our needs and desires at a different moment in our lives. Nao Bustamante's installation, "Chac-Mool," is a scented memory machine. It is a sacred place for devotion, imagination, and it is perfumed by guava fruit.

The artist uses the term "speculative reenactment" to describe much of the work in her exhibition "Soldadera." I find this to be such a useful term in that it really crystallizes how the artist works with the past through archival materials, different forms of history, period-specific fashion and technology, etc. At the same time, this act of looking to the past informs the show's critical utopian project of speculating about (writing, sewing, filming) the future or, to borrow a term from the late critical theorist José Muñoz, the "not-yet-here."1 Muñoz describes a queer-of-color utopian (or speculative) methodology as "a backward glance that enacts a future vision." It is a gesture of looking to the archival remnants and spectral presences of the past to use as the building blocks for some other, still unrealized, future world. This provides a language through which to describe speculative methodologies that constitute much of the work and curation of "Soldadera."

"Soldadera" is part of a larger body of contemporary Latino art participating in speculative projects of world-building. Last year, VPAM put on a career retrospective of the work of the late L.A.-based photographer and artist, Ricardo Valverde ("Ricardo Valverde: Experimental Sights, 1971-1996"). This multimedia exhibition included selections from Valverde's later, more experimental work, in which he transformed his portraits of East L.A. life through expressionistic embellishments that depict some radically alter-future world or moment of mystical revelation. In some cases he manipulated older work, or cut up and painted photos, creating modern renditions of 19th century photographic visual tricks. Frances Gallardo -- based in New York and San Juan -- uses weather technology imagery to craft elegant, delicate papercut illustrations of hurricanes that speak to human and environmental vulnerability in the face of devastating global climate change. The work of artists like Valverde and Gallardo reimagines slices from our contemporary moment in order to bring out the beautiful way that experimentation with our lenses of perspective, our materials, and our everyday senses can contribute to forms of necessary transformation.

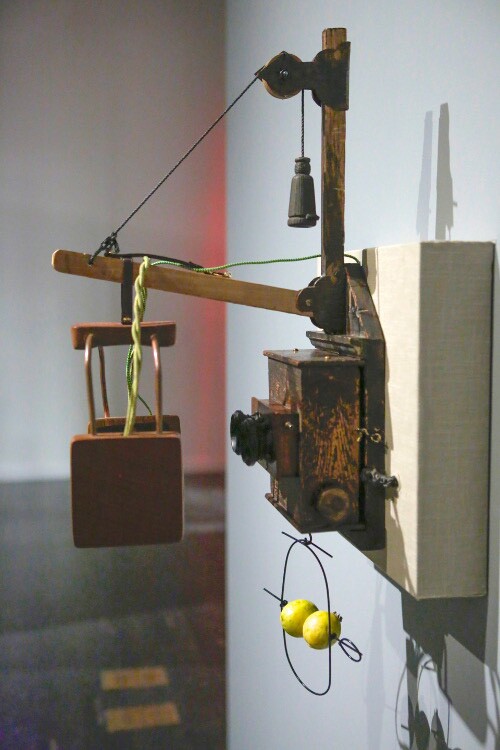

Bustamante's "Chac-Mool" fully engages the senses to achieve its inspirational, speculative effect. It is perfumed by two pieces of guava fruit, suspended at just the height of the viewer's nose. The mixed media installation, consisting of an old stereoscope viewer, a 7-minute video loop, custom built headphones and a vibrating upholstered stool, offers the viewer a semi-private opportunity to encounter the clapping rhythms of Leandra Becerra Lumbreras, the last known survivor of the Mexican Revolution, who recently passed in March 2015. The video, seen through the stereoscopic viewfinder, features Lumbreras reclined in bed, drumming a distinctive beat on a cookie tin and making improvised proclamations. The ambient electronic drums that accompany her playing, along with the smell of the guava, are moving in more ways than one.

You are meant to feel this work. The stool -- which you have to sit on in order to see the video and hear the soundtrack -- vibrates and rattles from a subwoofer installed within it. One can hear the tremors before discovering where they originate. Sitting on the stool, you feel the vibrations from the base of your spine as they move upwards and merge with the ethereal tones of the video, rendering the somatic and the sonic indistinguishable. The result is a complex, multi-sensory experience.

Lumbreras was a source of inspiration for much of the work of "Soldadera." The stitched peacock on the stool is modeled after some of her own needlework, displayed elsewhere in the show, in a vitrine, where it rests alongside archive photographs of the Mexican Revolution. "Chac-Mool" is paired with "Gallina, Post Revolución" -- a white crocheted doily in the shape of a hen, made by Leandra herself (in 1920) and given to Bustamante as a gift.

"Chac-Mool"'s title refers to a pre-Columbian reclining figure depicted with its upper back raised, head turned to a near right angle and knees drawn up. Traditionally, the ambiguously gendered chacmool's elbows rest on the ground and its hands hold a vessel on the stomach where offerings might be placed or sacrifices carried out. It is strongly associated with sacrifice and submission. In the words of one archeologist, "This recumbent position represents the antithesis of aggression: it is helpless and almost defenseless, humble and acquiescent."2 Because of its associations with sacrifice, the chacmool is sometimes thought of as a facilitator of connections -- of contact and movement -- between the world of the living and that of the dead. There is a 13th-century Chimú (Peru) textile depicting a chacmool currently on display on the third floor of the Vincent Price Art Museum, as a part of its permanent collection. Examples of the chacmool date back even farther, to the ninth century.

The intimacy of Bustamante's "Chac-Mool" protects its ancient and inspirational subject, Lumbreras, the last soldadera."Chac-Mool" displays a video of the woman who vitally informed the exhibition without crudely plastering her oversized image on the gallery walls. Such prominent exposure would seem to visit a kind of violence upon her, and the protective, domestic, even devotional display that "Chac-Mool" creates instead speaks to the show's larger engagement with feminine visibility and vulnerability.

This kind of viewing experience is a strong contrast with the commercially idealized -- often sexualized -- pop cultural image of the recognizable "Adelita" figure.

Bustamante's "Chac-Mool" has strong associations with confessional, Catholic privacy but also with more individual forms of everyday practices of spirituality, especially in a domestic context. Indeed the piece encourages a focused reverence for its subject and resembles a simple home altar. In this way, the piece works to blur the lines between art and (sacred) artifact, much like the prone dress on display under glass, "Tierra y Libertad, Kevlar® 2945," and much like chacmools themselves (which appear in museums as artifacts of a lost time). Bustamante encourages us to approach the objects in her show as archeological fragments and religious relics.

"Chac-Mool"'s material construction exhibits a "retro-futurist" aesthetic (like steampunk, but with wood). It has the look and feel of an elaborate, futuristic apparatus constructed (in the past) of found materials that visibly showcases its own technological components. The aged wood and "primitive" technology of a largely decorative pulley is seamlessly integrated with the work's stereoscopic video and large, square "headphones." The headphones can be adjusted slightly for user height but not so well for different head size. This imperfect fit, without a seal, ultimately serves to maintain an auditory connection with the rest of the exhibition soundscape, especially the loud soundtrack of the film projection, "Soldadera" -- an interpretation/extrapolation of the missing scene in Sergei Eisenstein's, unfinished film, "Qué Viva México" (1931-1932).

It was only upon a second, solitary visit to the exhibition that I was able to fully understand this leaky quality of the audio for "Chac-Mool" as a way of keeping it in touch with the rest of the artwork and the exhibition space itself. During the show's May 16 opening, people lined up to sit briefly at the installation, which was then practically inaudible. One guest even took schoolboy delight in compounding the piece's multi-sensory effects by anonymously touching people's shoulders as they sat straining to hear the audio-track. Despite the undeniable energy and excitement that was so densely packed into VPAM's small gallery space that night (nearly 400 people attended the opening), it seemed to be to be a less than ideal circumstance in which to approach this particular work. In this way, the work invited me to return to it later so that I could hear it well.

Upon revisit, however, I got the sense that interrupted listening, as an effect, is consistent with the show's speculative project of disrupting or disturbing our conventional expectations and experience of reality. The projected film, "Soldadera," is very much in the spirit of Eisenstein's revolutionary cinema (kino fist), deploying imperfect audiovisual synchronization and a montage of striking, provocative juxtaposition that creates a cognitive dissonance in the viewer. Its booming soundtrack competes with "Chac-Mool" but also converses with it (including the sound and projected image of Lumbreras's wrinkled hands, clapping rhythm).

The immersive and potentially meditative or reverent state that the installation encourages in the viewer enables experimental thought and feeling. Lumbreras appears as an almost mystical entity, with a bright, soft light emanating from her center and the source of the rhythms: her cookie tin drum. The reverberating, electronic rhythms that are built around Lumbreras's memorable beat are interspersed with mesmerizing synthesizer breaks within a repetitive, atmospheric structure. This creates the possibility for daydreaming and reflection, an ideal space for mental exploration. It is here that I was able to do my most productive and tranquil thinking. That is why I find it to be such a central part of this show. It seems to move one towards an altered state, which is so important for a speculative imagination that escapes and reshapes our already existing paradigms.

I understand "Chac-Mool" as a laboratory for the show's investment in speculative Latino art-making and the process of reimagining the past and the future. It generates a state of mind and body that is productive for experimental thinking. The show's speculative qualities make a space for marginalized voices to construct alternative futures that reject harmful inherited discourses and minoritizing iconographies. The show works to shape something else, an as-yet-known, mundo "Post Revolución" from the fragments of less visible histories.

Bustamante has talked about how the video of Lumbreras, as an artifact, provides non-narrative, affective access to an intangible past. "Chac-mool" engages all the senses and invites the visitor to enter into a hypnotic or meditative state, which is why it is such a productive site for speculative thought. The piece foregrounds its own materiality and relies on a non-linear, non-hierarchical conception of time, space, and the senses. In addition to the audiovisual track and the tactility of the installation's adjustable moving parts, the fresh aroma of guava fruits that hang below the viewfinder fully immerses the viewer in a kind of virtual reality experience that reflects Lumbreras's own domestic space. Indeed, the memory of Bustamante's January visit to Lumbreras's home in Zapopan is linked to the scent of guava that pervaded the house. Bustamante reflects: "The smell of guayaba followed me home from Zapopan. It is a smell sweet and cleansing, earthy and cosmic. It mingles with the air, is as light as air, becomes the air. This smell, which perfumed her home, will always bring me back to the experience of being with Leandra Becerra Lumbreras, the last survivor of the Mexican Revolution."

"Chac-mool" offers a spectral impression of the fragrant fruit and the lingering echoes of Lumbreras's clapping. Ultimately, the suspended guava will continue to decompose, transforming and projecting its scent. Such dynamic impermanence is emblematic of the show's overall emphasis on the speculative and the spectral. Each revisit offers a new, changed opportunity to rethink our world, where we've been and where we're going.

Notes:

1 See José Muñoz, "Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity" (New York University Press, 2009).

2 Mary Ellen Miller, "A Re-Examination of the Meso-American Chacmool," for Art Bulletin (1985), 7-17, 8.

Read more about Nao Bustamante's "Soldadera" project:

Nao Bustamante's Soldaderas, Real and Imagined

Nao Bustamante's exhibition "Soldadera" is a "speculative reenactment" of women's participation in The Mexican Revolution.

Searching for Soldaderas: The Women of the Mexican Revolution in Photographs

What can portraits tell us about soldaderas? Nao Bustamante draws from UC Riverside's archival holdings of photographs of the Mexican Revolution to investigate further.

Soldadera: The Unraveling of a Kevlar Dress

Made out of bulletproof Kevlar, Nao Bustamante's re-imagined Soldadera dresses protect the female body against violence.

My Love Affairs with Soldaderas

From calendars to corridos, the image of the Soldadera lives strong in popular culture. Nao Bustamante's new artwork re-imagines dresses of female soldiers.

Soldadera: The Tiny Things They Carried

Leandra Becerra Lumbreras was the last known survivor of the Mexican Revolution. Artist Nao Bustamante and a small crew made a trip to Zapopan, Mexico to meet her.

Soldadera: The Artist Meets Her Muse

At 127 years old, Leandra Becerra Lumbreras was the last survivor of the Mexican Revolution. Artist Nao Bustamante made a pilgrimage to her home in Jalisco, Mexico and found a muse.

Dig this story? Sign up for our newsletter to get unique arts & culture stories and videos from across Southern California in your inbox. Also, follow Artbound on Facebook, Twitter, and Youtube.