Stephanie Inagaki's Intimate Portraits

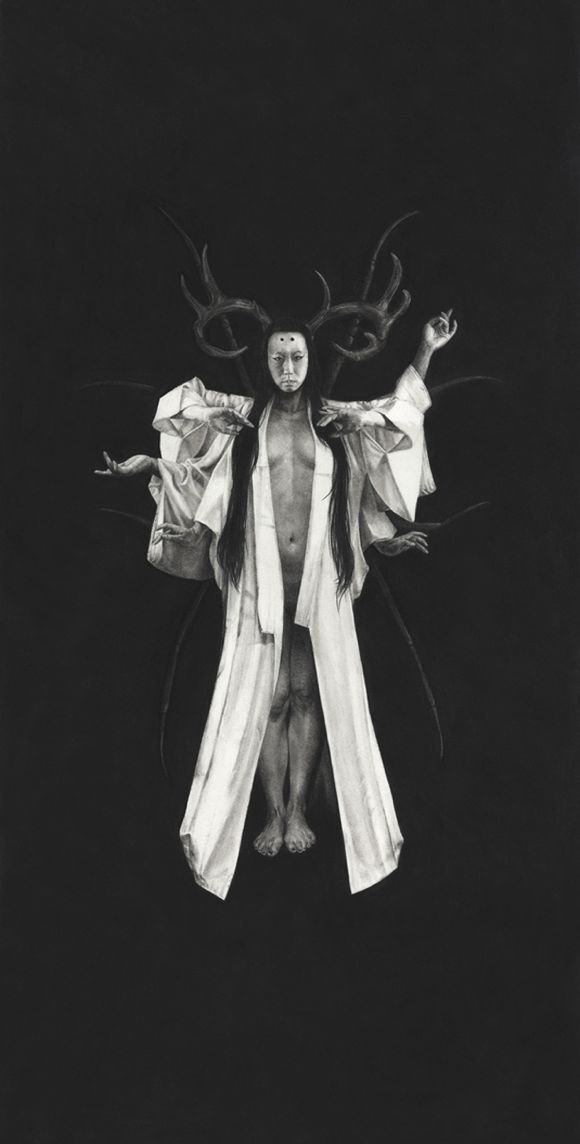

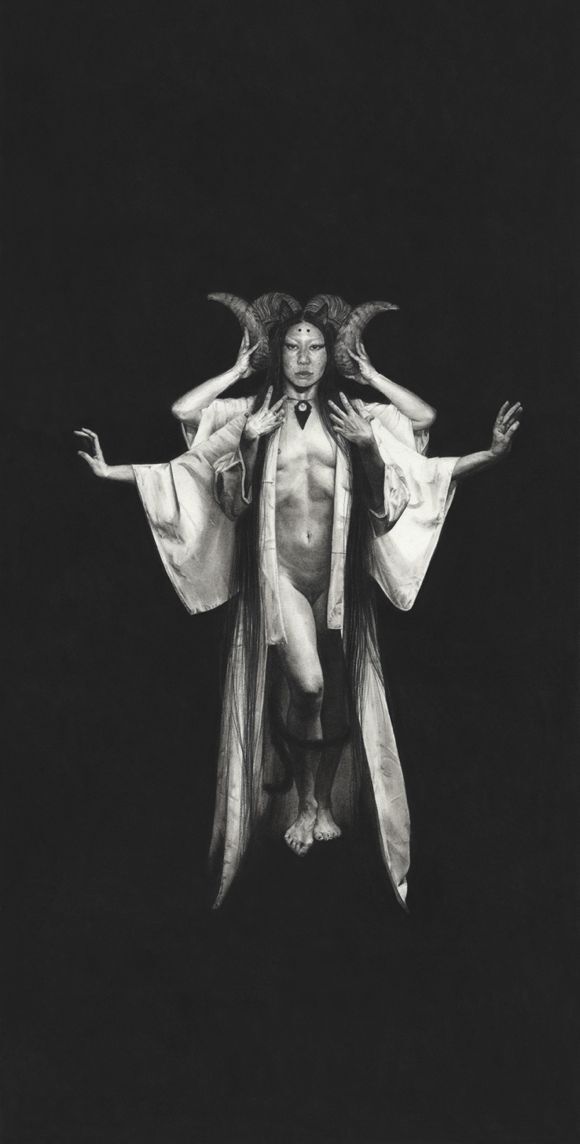

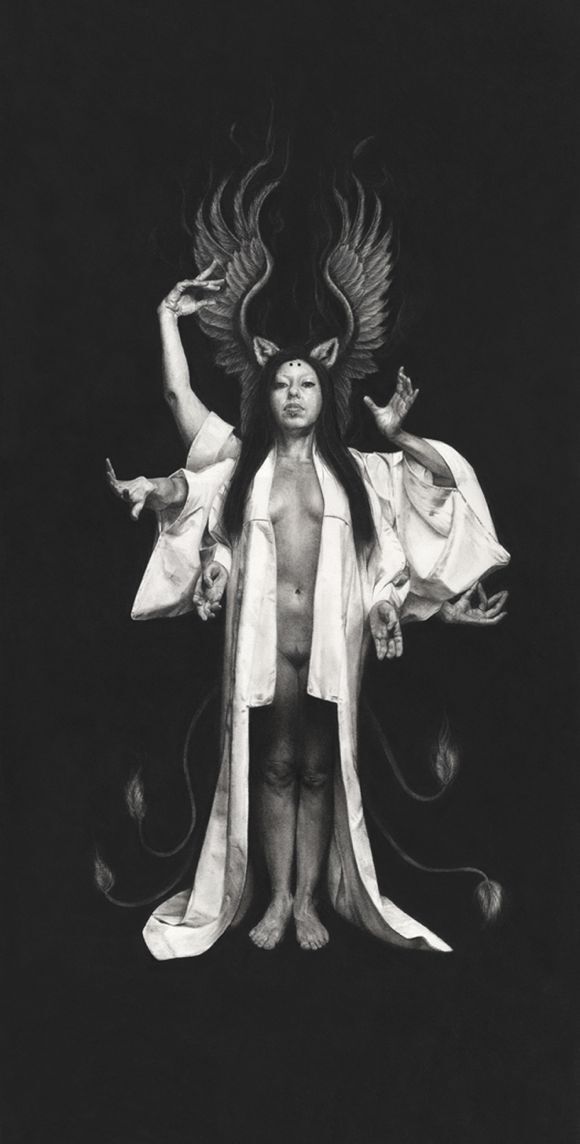

The women in Stephanie Inagaki's latest series of charcoal drawings are "Pillars." Standing straight-backed and strong-bodied, they are part-myth, part-mortal. One has the fins of a mermaid; another, wings and fox ears. Each has six sinewy arms with hands that flex and curl with all the grace of dancers. They are three of Inagaki's close friends -- Ver, Satine and Karen -- as well as the artist herself, creative confidants ready and capable of supporting each other. They have only known each other for a few years, but the bond in strong.

"I never had a role model," says Inagaki, who grew up in Camarillo and lives in Los Angeles. She adds that there's nothing wrong with that; She was reared to rely on herself. "Now, in my adult life, it's nice to have these strong women in my life that are supportive and they're creative and they're very driven," she says. "It's a great, positive environment to be around."

These new charcoal drawings debuted at Century Guild alongside works from David Mack and Bill Sienkiewicz on September 20. Inagaki considers her inclusion in the show a "huge honor." She is friends with both of the artists, who are best known for their contributions to the comic book world, and an admirer of their work. The show also marks a transition for Inagaki. Usually, she draws herself.

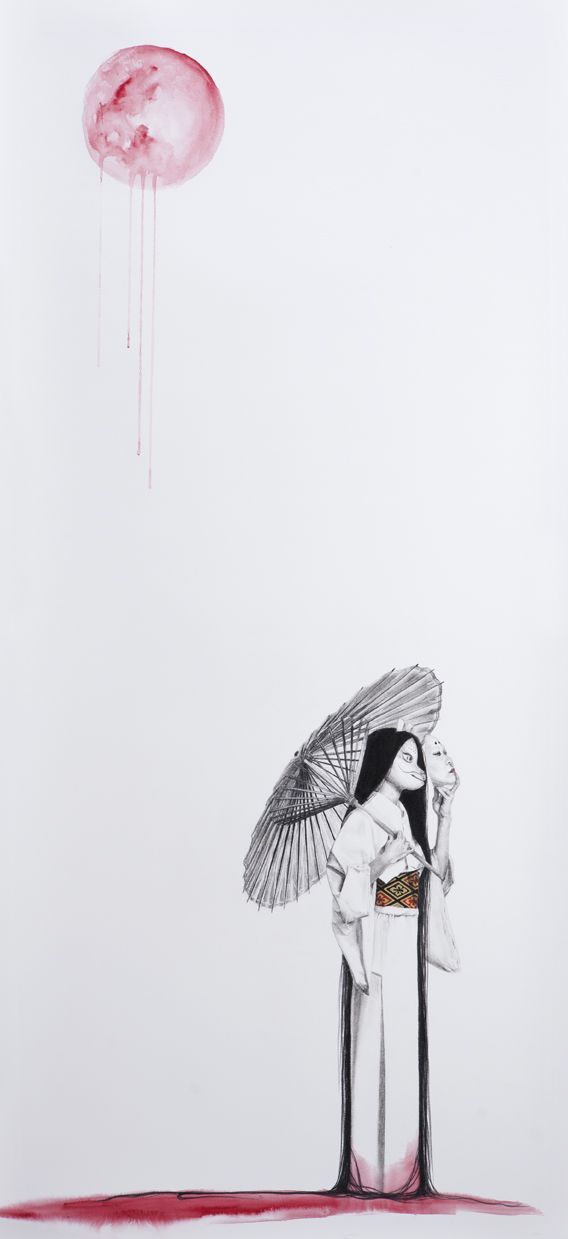

Inagaki's body of illustrative works is filled with self-portraits. Earlier this year, in her Century Guild solo show "Metamorphosis," the artist depicted herself in situations inspired by Japanese mythology and folklore. With charcoal, watercolor and washi paper, she does more than draw portraits, she creates worlds. Inagaki's drawings are filled with symbolism, like the extremely long hair that sometimes takes on a life of its own in the scenes. They are, the kind of drawings that would take hours just to begin comprehending the layers of meaning.

Sometimes, people approach Inagaki at art openings, asking, "What exactly does this piece mean?" This is difficult to answer -- "Do you want the long, honest answer, or do you want the watered down, art talk version?" she says -- but she does regularly write artist statements, succinct descriptions of the concepts behind the projects. In the statement for "Pillars," Inagaki writes, "It is a celebration of the feminine divine portrayed through our own mythologies. I represent myself as a pillar because I am a pillar for myself as well."

Inagaki likens the process of producing one self-portrait after the next to ongoing art therapy sessions. "Art is definitely a way for me to process, synthesize -- emotionally and mentally -- pretty severe events that's I've been through," says Inagaki. Right before Inagaki entered college, her brother died from leukemia. Shortly after she finished graduate school, her fiancé died. Even in times of grief, Inagaki's art flourished.

She studied sculpture -- undergrad at Boston University, grad at San Francisco Art Institute -- but it's been a while since Inagaki has worked in that realm. That's partially a logistical issue. She doesn't have access to the space needed to build the large installations in her head. That's the same reason why she shrunk down her drawings down from the life-sized pieces that she used to make. As a sculptor, she once cast 1000 vertebrae over the course of six months. One hundred of those were patinaed. The small pieces were suspended from 26 feet high and fell into an hourglass form at near the ground. "Depending on your perception, you can see it as ascending or descending, this pile of bones," she says. At noon, light would filter through a window, giving the piece a glowing effect.

Shortly before that, Inagaki made a series of sculpted neck pieces called "Exquisite Restraint." When discussing these pieces, she recalls an incident when her brother had a spinal tap. Inside a crowded children's hospital, he was given anesthesia, but the wait was so long that it started to wear off by the time of the procedure. Inagaki couldn't forget that and the incident went on to inspire her references to bones and the spine.

"Milton talks about how the earth is so fragile and it's hanging from this golden thread between heaven and hell," says Inagaki. "I kind of envisioned the human spine that way too because it's something that holds us up, but if you break it, you would just completely shatter and fall apart."

Inagaki's background in sculpture still shows when she works on her jewelry line, Miyu Decay. She shows one of her pieces during the interview, a fruit bat skull and bones made of brass. "It's not as conceptually heavy as the fine art," she says.

The concept is key for Inagaki, which is why she has done self-portraits so frequently. "Conceptually, it took me a while to figure out how to integrate other people into my work," she says. With "Pillars," she has been able to find her footing. "It's a lot easier for me to connect emotionally to my female friends because I'm female too," she says. That connection to the subject is what makes her images so powerful.

"I don't just draw images just because," she says. "I'm always compelled because of a concept that I have."

Dig this story? Sign up for our newsletter to get unique arts & culture stories and videos from across Southern California in your inbox. Also, follow Artbound on Facebook, Twitter, and Youtube.