Steven Schick: Percussionist Brings the Avant Garde to Ojai Music Festival

The ping and thrum, clatter and hum from nearby musicians sounds in the background while Steven Schick, on a quick break from rehearsals for this weekend's Ojai Music Festival, stays focused on the call.

As music director of the 2015 festival, Schick is speaking from the Brooklyn headquarters of ICE (International Contemporary Ensemble), one of the three new music groups -- he founded the other two -- that he will be conducting during the immersive four-day festival.

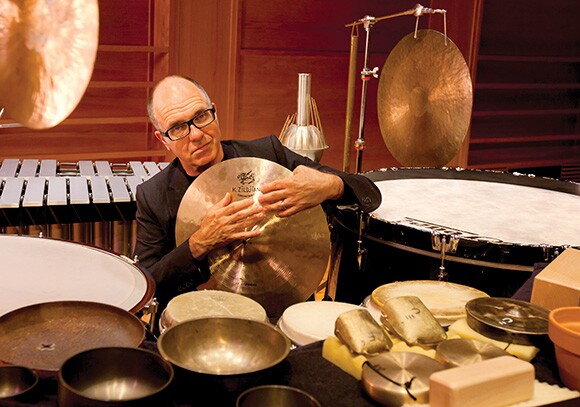

Schick, an astonishing virtuoso and boundary-crossing musician, is the first percussionist in the Festival's 69-year history to serve as music director.

His appointment by festival artistic director Thomas W. Morris, came as a happy surprise, Schick says. "I've played at Ojai, but never expected to be the music director. If I'm frank, I'm not in the same league as past directors like Pierre Boulez or Esa-Pekka Salonen. Maybe in terms of outliers, I belong, but I certainly wasn't a household name like most in the past."

Schick's trailblazing career in new music has been marked by an ever-expanding range of accomplishments, a calmly grounded personal temperament, and the kind of curatorial playfulness and acumen apparent in the Ojai programs. A Wednesday pre-festival prelude brings "A Pierre Dream," a multi-media piece unfolding in a Frank Gehry set and featuring Schick-conducted live music, archival film and recent interviews with musical innovator Boulez.

For the four following days and nights at Ojai, Schick has scheduled an exhilarating yet thoughtful series of 18 concerts, celebrating the 90th birthday of Boulez and featuring four programs that pair the esteemed Calder Quartet performing all six of Bartók's string quartets with related pieces by seven-time festival director Boulez.

Multiple programs explore dozens of works by other living composers, with none of the pieces for his percussion instruments, the 61-year old Schick says, being older than he is.

Most concerts feature Schick either performing (Friday night) or conducting (multiple days and nights) ICE, red fish blue fish and Renga. Red fish blue fish is the percussion ensemble Schick founded early in his 25-year tenure as a music professor at the University of California, San Diego, and Renga is a newer group, an "art for the people" chamber orchestra comprised of members of the San Diego Symphony.

"We've been talking for 18 months, and the Bartók and Boulez pairings came out of a conversation with Tom Morris," Schick says. Other, more contemporary choices such as Chinese pipa virtuoso Wu Man playing Lou Harrison's concerto for her instrument with ICE, he says, "I didn't have to sell Tom on any of that."

Several choices reflect Schick's taste for natural sounds and sites, as well as his ease with music-making marathons. John Luther Adams' "Sila: The Breath of the World," is a 75-minute piece, its meditative atmosphere produced by 80 peripatetic musicians who will offer this free Thursday afternoon concert in the festival's downtown venue, Libbey Park. On Saturday late night comes the west coast premiere of another poetic nature piece by Adams, "Become River."

The next morning Schick will play (with flutist Claire Chase and pianist Sarah Rothenberg) Morton Feldman's more than four-hour long "For Peter Guston." That performance begins at 5 a.m., kicking off a closing day that ends with the music director playing and conducting in the final Bartók-Boulez concert that evening.

Fit, eloquent, preternaturally energetic, Schick was the founding percussionist and a 10-year veteran of the famed, New York-based Bang on a Can new music ensemble. "Twelve hour concerts were nothing for us," he says of that groundbreaking group, several of whose members are joining him as players or composers at Ojai.

Schick is also the author of a seminal text, "The Percussionist's Art," as well as scholarly articles on such heady subjects as contextual clues for memorizing the long and difficult score of Brian Ferneyhough's "Bone Alphabet." Late last month, Schick was appointed as the inaugural holder of the $1 million Reed Family Presidential Chair in the Division of Arts and Humanities at UCSD where he is a distinguished -- and revered -- professor of music.

Yet not only does Schick express happy surprise about his appointment as music director at Ojai, but also he sees serendipity at work in other turns his burgeoning career has taken.

He began conducting just ten years ago, he says, and "totally by accident." As a representative of UCSD's innovative music department he attended a 2005 meeting of the La Jolla Symphony & Chorus, a community orchestra "affiliated" with, though not staffed, by the university. "They were concerned because they had just lost their conductor and weren't able to find a replacement. I found myself having this kind of out of body experience in which I watched myself raise my hand."

Seated nearby, the chairman of his department reminded him, "You don't know how to conduct." And Schick reminded himself that as a champion of new music, he was unfamiliar with much of the standard repertory the orchestra played.

Still, he says he asked himself: "How bad could it be?"

"It" -- his conducting -- was so good that the La Jolla Symphony board spent two years searching for a full-time music director, and, after interviewing four other candidates, "On the strength of my performances with them and to my surprise, they hired me."

He's since made a reputation for the La Jolla group with his brilliant juxtapositions of classical and new music, the ambition of his progressive repertory taking both audiences and players along with him.

Schick was one of five children in an Iowa farming family. His mother was an amateur pianist and he calls himself "a product of the public schools of Iowa which all had a music program that began in first grade. I was never going to be a professional musician, but I played percussion in the band in the school, and I later played in rock bands."

It was not until he switched his major from pre-med to music at the University of Iowa that Schick began taking himself seriously as a professional musician. He completed undergraduate and graduate degrees there, held a number of assistantships, a Fulbright fellowship in Germany. During grad school commissioned his first piece, a duo for percussion and piano.

"I remember going to the bank with my then-wife Wendy, and taking out five hundred dollars which was more than half of all we had. I am eternally grateful to her that she said, 'It's only money'." Since then Schick has commissioned more than 150 other pieces, more than doubling the repertory for solo percussion.

He calls the commissioning of new work "the single most optimistic thing a patron can do to create a musical culture," and with characteristic perspective, he says the number of his commissions pale in comparison to those of someone such as his late friend, the philanthropist Betty Freeman. She commissioned more than 500 new works from scores of composers, even early in their careers.

Often praised by critics for being "fearless" or "courageous" in his musical explorations, Schick issues another disclaimer.

"What others may think of as boundary-crossing or fearlessness is simply an aspect of being a percussionist. If you take the lessons of your instruments seriously, you realize that those boundaries between genres, they're artificial. As a percussionist you follow your nose in a way. If I had been a violinist looking to establish a career I might not have done (the breadth) of what I did, especially with new music. But as a percussionist, it's what you have to do. It's a way of life."

Bonnie Wright, founder of San Diego's Fresh Sound series, a downtown showcase for new music, credits Schick with "changing the world of percussion and contemporary music by all he does to bring this kind of new music into the popular consciousness."

He was the first artist Wright presented on her series in 1997. No ivory tower academic, she says, he's "totally engaged in the community. He's really funny and really smart and he has the best memory of anybody I've met in my life. He memorizes all those pieces."

Wright refers to Schick's huge solo performance repertory that also includes the syllabically inventive Dada poem "UrSonate." He'll perform that wild masterpiece by the often-exiled 20th century artist Kurt Schwitters in Friday night's American premiere of a staging by director Roland Auzet with video and live electronics by designer Wilfried Wendeling.

Many of Schick's percussion students have gone on to successful solo careers, and, in addition to his teaching and music directing for the La Jolla Symphony & Chorus and the Ojai Festival, he also directs the San Francisco Contemporary Music Players. He was admitted into the Percussion Hall of Fame last year.

Music historian Christopher Halley has written of Schick that "No one has done more to champion, interpret, and expand the repertory of contemporary percussion music than Steven Schick. Not only has he mastered the entire solo repertory -- and more than doubled its size through commissions -- but as a conductor, educator, and author he has deepened our understanding of the role of percussion in music's past, present, and future."

Given his aesthetic and cultural range and the breadth of the 2015 Ojai concerts, does Schick have a favorite coming up this week in the bucolic valley?

"That's like asking which one is your favorite child," he says, and laughs. "I'll answer you anyway. Perhaps what I care about most is the difference between the Friday and Saturday night concerts."

Part Two of Friday night's program is a solo percussion recital Presenting Steven Schick in a program of works by pioneers Iannis Xenakis and Karlheinz Stockhausen and their successors such as Finnish mid-career composer Kaija Saariaho and the Pulitzer Prize-winning American innovator (also associated with Bang on a Can), David Lang.

That solo recital is followed by "a late night concert with all kinds of solo and duo playing." Included are the Schwitters "UrSonate" and a favorite in which Schick is joined by cellist Maya Beiser -- another founding member of Bang on a Can -- for Osvaldo Golijov's "Mariel" for cello and marimba. It's the first piece they commissioned as a duo.

On Saturday night, by contrast, Schick will mostly be conducting. The range of players will include the Calder Quartet, ICE for which he is a resident artist and Renga which he cofounded with Kate Hatmaker. The colorful range of pieces include the Lou Harrison concerto for Wu Man and her pipa, as well as a world premiere by another Bang on the Can veteran, Julia Wolfe.

Late night brings together very different yet complementary American pieces, Aaron Copland's classic "Appalachian Spring" and Adams' "Become River."

Playing -- in all senses of the word -- and conducting, Schick says, "The juxtaposition of those two things within 28 hours, with all those diverse threads representing all the things I care about most in music, I may never have another opportunity as thrilling as this."ar

Dig this story? Sign up for our newsletter to get unique arts & culture stories and videos from across Southern California in your inbox. Also, follow Artbound on Facebook, Twitter, and Youtube.