The Pioneering Aviatrix Who Helped Preserve Native American Basketry

The following article is edited and re-published from California Desert Art, a doorway to the rich bohemian world of early desert artists.

In a bedroom tucked up as far as you can go against the mountain, Rose Gray Dougan lay dying. She could feel the cool shadows slide down Mount San Jacinto at night. From her perch at the end of Arenas Road in Palm Springs, she could look right into Tahquitz Canyon, lair of a Cahuilla spirit who masqueraded as a fireball. Far from her aristocratic beginnings, Rose was now close to the elemental. Exactly where she always wanted to be.

If you had a chance to look around her home, you might have seen clues to her life as an advocate of Native American arts, pioneering aviator and adventurer: A photo of Rose in the cockpit when she was a student of the Wright Brothers. Rose with her Russian noblewoman lover, Verra von Blumenthal, and the adobe castle they built north of Santa Fe. Rose and another star-powered partner, Florilla White — one of the famous Palm Springs White sisters.

On her dresser you might notice the Cahuilla baskets on display. Rose and Florilla traversed the desert from Morongo to Anza, meeting Cahuilla Indian basket weavers and promoting their work. A self-described "rabid crank on the subject of liberty for the Indians," Rose fought for fair pay and prestige for Native artisans both in Santa Fe and Palm Springs. In other accomplishments, she was the force behind the first animal shelter in Palm Springs as well as the earliest low-income housing.

If ever there is a Palm Springs LGBTQ Hall of Fame, Rose Dougan (1882-1960) will surely require her own wing. For now, though, I only know her name because of a passing comment by Cathedral City historian Denise Cross. "Flying Rose is about as marvelous as it gets," said Denise, who bestowed the "Flying Rose" nickname. "She and Verra are women with a cause. They are great women of American history."

Looking deeper, I found this great woman to be uncommonly elusive. She guarded her privacy to protect her wealth. There are few photographs of her in existence. She once said she preferred to be "altogether unnoticed — and so altogether at peace." I might have given up on ever finding Rose, but then I read an essay by New York historian Brigitte Dale arguing that stories of women of color and LGBTQ women often are lost for just this reason: scant evidence. (Dale was discussing the Apple TV show "Dickinson," specifically.) "Embrace historical fuzziness," Dale urged. "Put these stories front and center." Armed with the permission to speculate, I forged on.

Much of what we do know about Rose Dougan is thanks to Santa Fe teacher Jessica Levis and her 2007 master's thesis for New Mexico Highlands University: "The Rise of the Santa Fe Aesthetic: The Von Blumenthal-Dougan Project." Rose Dougan (also spelled Dugan at times, perhaps to further protect her privacy) was born in Richmond, Indiana, and grew up in Denver, Colorado, after her family later moved there. Her father was a doctor and a banker. Her uncle Daniel Gray Reid was a multimillionaire steel magnate. Young Rose attended the Quaker-based Earlham College in Richmond where she absorbed Quaker values of social justice.

She studied music in Paris, and read psychology and philosophy on her own in a relentless quest for betterment. "Personal development is the meaning of one's existence on this earth," she later wrote to a friend.

One way she bettered herself was by learning to fly with Wilbur Wright in a cow pasture eight miles north of Dayton, Ohio. Now famous as the world's first airfield, the site was the home of the Wright School of Aviation. Rose was one of only three women who attended in 1915. "Rich Girl to Fly Plane," an Los Angeles Evening Express headline read.

"I have no fear of altitudes," Dougan told a reporter. "Why should one be afraid?" Indeed, Rose proved her fearlessness by volunteering to fly in France during WWI, but her offer was rejected.

Like many restless spirits of the era, she headed west to Santa Fe, where she again made aviation history. In 1916 the Santa Fe New Mexican reported on "the dashing aviatrice" who flew her plane over the city with "the elderly Mme. Countess Blumenthal of Russia." Madame Verra now enters the scene, and Flying Rose goes down in Santa Fe legend as the first person to fly over the city.

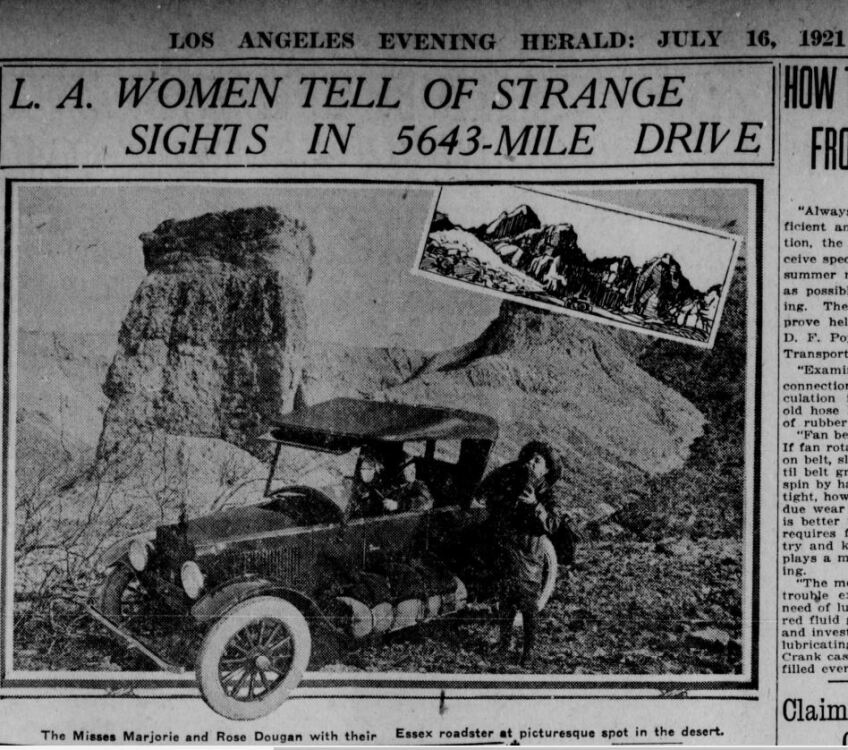

Rose made another appearance as a public daredevil in 1921 when she and her niece Marjorie took "the longest all-woman drive" in the Southwest. Their 5,643-mile spin in an Essex Roadster took them to petrified forests and ancient Pueblos, cementing Rose's hunger for what she called "the eloquent past."

Rose soon joined a lineage of moneyed women — Mabel Dodge Luhan, Millicent Rogers and others — who moved West and worked to preserve Indian culture. "I have felt for a long time that something should be done to preserve and encourage the only real national art we have," Rose wrote in a letter to Paul A.F. Walter, secretary of the School of American Research and founder of El Palacio magazine.

Rose was an example of the New Woman, a subset of post-Victorian women intent on throwing off limited female roles, turning away from industrialized society and seeking authenticity in the ancient cultures of the West. As Jessica Levis writes, these women "would bear few, if any children, and would seldom marry."

Another example of the type was Rose's sister Blanche Dougan Cole (1868-1956). She studied painting at the Académie Julien in Paris and lived among the Moqui Pueblo Indians in Arizona in 1898, while working as an artist sponsored by the Santa Fe Railroad. Both Blanche and her husband William H. Cole became established painters living in Los Angeles.

Rose took the New Woman template to new heights when she teamed up with her duchess (not a real duchess, but descended from Russian nobility) and built a home and studio on an ancient pueblo site called Tsankawi in the juniper and pinon country north of Santa Fe. Los Alamos researcher Kit Ruminer guesses they chose the location due to nearby clay deposits and water sources for pottery-making.

The ancient Indian cave dwellings just above the building site suggested earlier residents also found it a fertile setting. Rose seemed well-pleased with her castle, referring to it as "my cabin on the Mesa" — as if she was starring in a feminist Zane Grey romance. (While Rose and Verra have been embraced as historic foremothers by the local LBGTQ community, Ruminer says she found no direct evidence Rose and Verra were romantically involved. This is one of those areas of historical fuzziness Dale talks about.)

Rose's partner, 20 years her elder, was named Verra Xenophontovna Kalamatiano de Blumenthal. The "von" was a later adaptation. She was born in Russia around 1864, and worked to promote the work of Russian folk artists and lacemakers. Like Rose, she believed that women of means should help Native women artists survive.

Verra was 5" 1" with olive complexion, a high forehead, a long aristocratic nose and a hunger for attention. One article called her "the tiny duchess." Another said she was "a beauty, a flirt and a spy." (It was actually her son Xeno, who became a spy, according to Ruminer. Ruminer was a site watcher at the Duchess Castle ruins and was impelled to do more research on Rose and Verra.)

Rose was also small, qualifying her as the tiny aviator at the side of the tiny duchess. An article described her as "a quiet, charming and petite brunette…she did not mingle much…" (The petite crusader would grow portly in her Palm Springs years.)

Rose and Verra's Santa Fe compound came to be called Duchess Castle. Today you can visit the ruins of Rose's dream in Bandelier National Monument. (Jessica Levis came upon the subject for her thesis after she spotted the Duchess Castle ruins on a hike, and realized little was known about the castle builders, Rose and Verra.)

The couple worked with potters from San Ildefonso Pueblo, offering workshops, marketing strategies and financial aid. Their work gained the support of now-famous archaeologists Kenneth Chapman and Edgar Lee Hewett, leading eventually to the Indian Arts Fund and then, in 1922, the first Santa Fe Indian Market. The event remains central to Santa Fe's cultural scene, securing Rose and Verra a place in New Mexico history.

When the pair came on the scene in 1917, Pueblo pottery designs had been compromised. Native potters were encouraged to crank out patterned ash trays and fake rain gods to feed the tourist market. Rose and Verra joined a faction that opposed the curio trade and worked to restore traditional designs.

Around the time Duchess Castle was operating (1916-1920), Verra also opened a center for Indian crafts at a home she owned in Pasadena, at 35 North Euclid. The couple apparently traveled back and forth from Santa Fe to Pasadena, meeting Native artisans in both places.

A rare account of the patrons from the artist's viewpoint comes from Maria Martinez — a world-renowned potter of the San Ildefonso Pueblo — who was invited to Duchess Castle to make pots: "And there was a lady, two ladies. One was old and the other was young, and they had a ranch out there in the Pajarito Sankawai." Martinez went on to say that she made a pot for the women's open house and earned seven dollars for the piece.

In the 1920s Rose and Verra departed Santa Fe, leaving the operation of Duchess Castle to the influential School of American Research. The buildings and a small chapel were abandoned. On a 1967 visit a writer for Desert Magazine found Duchess Castle had mostly crumbled: "Mallow and other wild flowers decorate the silent grounds."

The Palm Springs Years

Verra and Rose parted and Rose wound up in the Coachella Valley on her own, moving first to Indian Wells in 1937 where she bought a ranch at Point Happy. The location is significant as the site of a major Cahuilla village, but we don't know who or what brought Rose to Point Happy or even to the Coachella Valley. Possibly the draw was Florilla White, a homeopathic doctor who came to Palm Springs in 1913. In a book about gay Palm Springs — "A City Comes Out" by David Wallace — Rose and Florilla are mentioned as a "fairly out couple" who lived together.

Florilla's sister Cornelia was one of the earliest supporters of the Palm Springs Art Museum, donating property for the original museum. Another sister, Isabel, married author and photographer J. Smeaton Chase in 1917. By getting together with Florilla, Flying Rose had in effect married into Palm Springs royalty. She'd remain in the desert until 1943, departing after Florilla White died, and returning to live in Palm Springs again from the 1950s until her death in 1960. (Verra von Blumenthal died in 1942.)

Given Rose's devotion to Native arts, the California desert must have come as a bit of a cultural shock. While Santa Fe was teeming with anthropologists, artists, museums and sophisticated New Women from the east, Palm Springs was still a sleepy Hollywood annex. Once Rose moved to the California desert, documentation of her activities largely vanishes. The Santa Fe pottery scene is well-studied and Rose shows up in archives there; little is written about the Palm Springs basket collecting scene.

From what we can see, it appears that Rose was trying to replicate the work she and Verra began in Santa Fe. Again, she was tracking down Native artists, paying them for their work and encouraging traditional designs rather than tourist trinkets. But few clues remain, just a scattering of Desert Sun news items: Rose installs one of the desert's first air conditioners at her Point Happy ranch; Rose and Florilla White go riding with the Desert Riders, Rose and Florilla volunteer for the Red Cross Motor Corps — transporting military supplies — and purchase an ambulance for the use of the squad.

Another news clip shows Rose and Florilla White leading an effort to build the first modern animal shelter in Palm Springs. The land they purchased for the project was in escrow at the time of a 1941 Desert Sun news story; it's not clear if the shelter was built.

Rose later built the Palmer Steel Court housing on Indian in Palm Springs (now gone), possibly the earliest low-wage housing in the city. The nine duplex units, intended to house workers, were featured in Architectural Forum in February 1938. Rose also owned the Caliente Cottages at 425 S. Indian — also gone.

Along with her community activism, her social life, construction projects and her philanthropy — all along Rose was quietly collecting the baskets of the Cahuilla Indians.

If you want to know why Indian baskets are so important as art and culture, there is boundless non-Native scholarship regarding their design, history and symbolism — but only recently have Native writers and artists begun to weigh in. A Tongva artist, Weshoyot Alvitre, explains that baskets "are actual living ancestors…They were relatives for much longer than they were fancy trinkets for tourists to buy," she writes. (For a compelling introduction to the topic, see the comic book "My Sisters" by Weshoyot Alvitre and Chag Lowry.) We can, then, think of each basket preserved by Rose Dougan as a sister. A person saved.

The Basket Craze

Rose was part of a nationwide movement of collectors, art dealers and ethnographers determined to capture these ancestors before the artform disappeared or was watered down by the tourist trade. The "basket craz," as it was called, was jump-started in 1884 by Helen Hunt Jackson's "Ramona" novel. George Wharton James (known for his Palm Springs classic "The Wonders of the Colorado Desert") wrote the influential work, "Basket Makers," in 1901. Railroad tourism further drove the trend, and many wealthy homes added an "Indian corner" to showcase their basketry and pottery collections.

Preservation sometimes crossed the line into exploitation, of course. But the New Woman collectors for the most part simply wanted to keep the tradition alive at a time of major changes. Grace Nicholson, for example, had a well-known shop in Pasadena; it's likely that Verra and Rose were influenced by her. (Another "Grace" famous for basket collecting was Grace Hudson, namesake of a museum in Ukiah.)

While Grace Nicholson traveled all over the West — paddling up the Eel and Trinity Rivers in small boats to visit weavers — we can guess that Rose and Florilla, in turn, tooled up and down Highway 74, into the canyons behind Morongo, and spent time in Anza and the Santa Rosas getting to know the women and their work. Rose would have learned to recognize a deer grass bundle, yucca, sumac and dyed juncus. She likely knew who wove the best diamondback rattlesnakes in the desert. (That would be Guadalupe Alberas.)

Flying Rose instinctively understood the importance of preserving the identities of the individual artists and faithfully recorded the names of weavers in her collection: Dona Tortes. Fanny Casseras. Cleo Torres. Dolores Lubo. Not all collectors were so enlightened.

Scholars such as Yve Chavez have pointed out that individual artists' names were often erased at the height of the basket craze. While anthropologist Alfred Kroeber used the term "Mission baskets" in 1922 to refer to all baskets by the so-called Mission Indians, modern descendants prefer to keep the distinct identities of tribes: Luiseno, Cahuilla, Gabrieleno-Tongva, Chemehuevi, Serrano. The artists, too, are to be recognized by name, just like a Ruscha or Banksy.

How did this large, wealthy white woman come across to the Cahuilla artists? Unfortunately, no documents survive to tell us how the weavers regarded Rose Dougan. Jeanian Espinoza, the great-granddaughter of basket weaver Guadalupe Alberas — her baskets were collected by Rose — says the Native side of the story is largely erased because the tribe's stories are oral, not written. Historical fuzziness applies here as well. Asked how Rose would have been received, Espinoza can only surmise: "At the time, the women probably would have appreciated the income." Espinoza is tribal librarian for the Santa Rosa Band of Cahuilla Indians headquartered near Anza, a place Rose and Verra must have visited often.

Jessica Levis says of Rose and her art collecting: "She was not there to get fame and fortune out if it. It was very much from the heart."

Aftermath

By the time Flying Rose was dying of cancer in 1960, Florilla White had passed away. At Rose's side was a nurse and companion named Travis Bishop. Just weeks before Rose died, she altered her will (or Travis said she did) to leave everything to Travis. In fairness, Rose might have intended to leave her nurse everything. But by another interpretation, this could have been Rose's lifelong gold-digger fear coming true at last.

Rose's niece, Marjorie Dougan, contested the will and won. (Marjorie was the daughter of Rose's sister Blanche. Marjorie adopted the last name of Dougan, for reasons lost in the historical haze.) But when Marjorie died only a few years later, the estate had not been settled — leaving a cliffhanger: What became of Rose Dougan's riches?

Any clues to be found in Rose's papers are gone. Kit Ruminer says all of Rose's personal papers were burned at her own request after her death.

The missing papers have proven frustrating for Colorado writer Becky McCreary. She has been collecting material on Rose for years ("She is under the bed in a suitcase right now") and plans to write a book about her. She says she came to a standstill researching the Palm Springs years: "One hole is what happened to the family fortune? Another is Palm Springs. Palm Springs and the money are my missing links."

Many of Rose's Cahuilla baskets went to museums, including the Southwest Museum and the Palm Springs Art Museum. Palm Springs Art Museum archivist Frank Lopez found 27 baskets in the museum's holdings labeled: "Gift of Cornelia B. White from the Marjorie Rose Dougan Collection." These were Rose's baskets inherited by Marjorie Dougan, then passed on to Cornelia White when Marjorie died.

The whole time I've been working on this story, Rose has always felt just out of reach. The surviving documentation is not quite enough to get close to her. But on the afternoon I walked up toward her mountainside home — just below the great gash of Tahquitz — that's when I finally found Flying Rose. She had been a larger-than-life cut-out, but now she was a real person who had lived not far from me. People's stories are contained not only in burned letters and old newspapers, they also live on mesas and in mountains.

Writer's note: Thanks to Denise Cross in Cathedral City, Jessica Levis in Santa Fe, Kit Ruminer in Los Alamos, Becky McCreary in Colorado and Frank Lopez in Palm Springs. All have helped to preserve Rose Dougan's story. If you know more about Rose Dougan and Verra von Blumenthal, contact Becky McCreary who is writing a book on the topic: RebeccaMcCreary764@gmail.com