The Triforium: A Second Life for Los Angeles' Polyphonoptic Sculpture

It's not uncommon for a work of art to be critically maligned, only to be recognized later as a historically worthy piece. After all, it took about 25 years for Picasso's "Les Demoiselles d'Avignon" to be acknowledged as one of the most sterling examples of Cubism. The Triforium, an odd-duck of a public sculpture by Joseph Young, is finally finding its footing as a vital work in the L.A. landscape thanks to a faction of devoted enthusiasts called the Triforium Project.

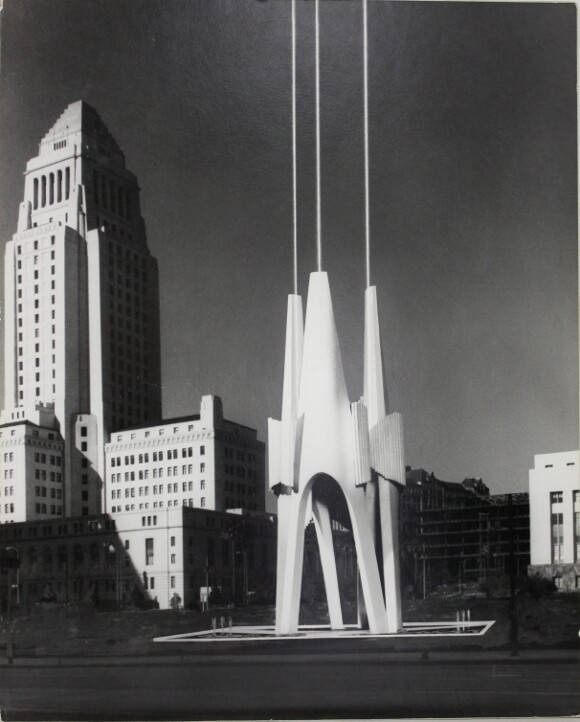

In 1958, Los Angeles bested Long Beach in a bid to get a new Federal Building under the condition that they would build a park or a plaza for downtown workers to enjoy lunch. The architect of that plaza, Robert Stockwell, commissioned locally noted mosaic artist Joseph Young to craft a public art piece. "The Triforium was considered a key part of that park, because it was going to be a draw, and it was going to get people here after hours, and so the city invested quite a lot in it," said architectural historian Daniel Paul in a speech during a fundraising kick-off party on a recent chilly December night at the foot of the peculiar six-story downtown structure in the Fletcher Bowron Square above the Los Angeles Mall's North Mall on Temple and Main.

Thus, the effort to raise money to restore and update the Triforium began with a birthday party -- on the undraping of the sculpture's exact 40th anniversary -- but it also served as a reminder that the history of the sculpture is fraught with failure and indignity. See, the Triforium was already despised by the time it was unveiled in 1975 in a ceremony featuring pop stars Burl Ives and Eddy Arnold. The funding for the sculpture had ballooned from its original $330,000 budget to $925,000, causing one city councilman to denigrate the Triforium as "the million dollar firefly."

"It was unveiled in 1975, and basically from the moment it was dedicated, it was never fully functional," Claire Evans (of the band Yacht and the mobile app 5 Every Day), one of the key proponents of the Triforium's restoration, told Artbound in a phone interview. "The computer system that was supposed to synchronize the light and sound effects never properly worked, and it became a highly contested, highly political 'waste of taxpayer funds.'"

The bloated budget came from the fact that the project was too ambitious for its time. Over the course of the kick-off event, presenters would describe the Triforium's original concept in terms that seem outrageous even for today's most conceptual art and technology employing artist.

"He wanted to invent a new theory that would interweave color and music through the technology of the Triforium," said Leslie Young, one of the artist's two daughters who spoke recently at the fundraising event.

"As part of his fantastical plan, my father proposed that laser beams would shoot skyward from the three concrete pillars, tapping out Los Angeles in Morse code," said Cecily Young, Joseph Young's other daughter.

"He wanted the lasers to shoot up into the universe, and not only blink Los Angeles in Morse code, but after going to the 1970-71 art and technology exhibit at LACMA, he spoke with Rockne Krebs, who was a famous laser artist, and got ideas for tilting the lasers sideways so that the lasers would hit buildings and the lasers would reflect off of Libbey-Owens-Ford mirrored glass that would be outside the buildings across Los Angeles. And then he researched beam splitters so that the lasers would split, and the whole city would be connected by lasers from the Triforium," said Paul. "The budget was not there for the lasers."

What did make it from the drawing board to the Square was still a reach for the technological capacities of the time. "This is not an entirely substantiated thing, but I believe the Triforium was possibly the first interactive light and sound sculpture," Evans said.

In fact, Young coined the term "polyphonoptic" to describe the mixture of sound and light that came to define the sculpture. He was inspired by Louis Bertrand Castel, an 18th century Jesuit mathematician who developed an instrument called the "ocular organ," in which a keyboard corresponded to slides of stained glass, which would essentially make what was called color-music. As well, his wife, Millicent, was a concert pianist, and music was always being played in the home. "He was really interested in this new language combining music and color, and he wanted the Triforium to reflect an ambition," said Paul.

The final version of the Triforium consists of three gargantuan concrete wishbones -- modeled after LAX's Theme Building and symbolically representing the three branches of government -- upon which are affixed nearly 1,500 Murano stained glass slides with incandescent bulbs to light up in a glittering prismatic spectacle. The idea was that the bulbs were to interact with a variety of catalysts: pedestrian footfall, the public's conversations picked up by a mic underneath the center of the Triforium, and the music played from the control room. At the fundraising kick-off, tours were given of the control room -- a largely neglected room in the lower part of the mall, now across the way from a Sbarro -- by Tom Carroll from "Tom Explores Los Angeles," a sort of YouTube version of Huell Howser's "California Gold" (Carroll, who was a classmate of Evans's at Occidental College in the mid-2000s, first explored the Triforium on his show, and was one of the main stimuli for the restoration effort.)

In the control room, Carroll pointed to the area where a double keyboard (in Flemish and English octaves) sat that was connected electronically to a 79-note Benjamin Franklin glass bell carillon designed by legendary glassware maker Gerhard Finkenbeiner. The bells were then piped out onto speakers on the Triforium. "It had a TEAC reel-to-reel that would play music, and people like Bill Vestel, who was the music program director for 10 years, would play classical [music], would play the Beatles, would play Chicago. Skip Kennen, one of the other musical directors, played Cream on it."

Unfortunately, the audio aspect proved distracting for a prickly night court judge in the Los Angeles Superior Court across the street, and he petitioned to have it silenced in the 1980s. And that's how the 60-foot-tall, 60-ton potentially kinetic behemoth became an inert sculpture for about 20 years. Coupled with the park's relative inaccessibility, the Triforium has basically been abandoned. This despite the fact that Young had been inspired by his travels in Europe; the Triforium was meant to bring people into the square like an Italian piazza. "It's so part of the visual landscape that people have forgotten about it," Carroll told me at the event.

But the Triforium holds too much power to be completely lost to apathy. It was too inspiring. "I came to the original opening when I was a kid," said longtime downtown resident Santiago Pérez, at the kick-off event. He was so inspired by the Triforium that he embarked on a long career as a computer engineer, from which he is now retired. "I loved that thing."

And in 2006, then-councilwoman Jan Perry mustered the support to replace the incandescent bulbs, giving the Triforium a short-lived resurgence. And then came along the Triforium Project. "To have this great thing that's just hiding in plain view was really exciting to us," said Jona Bechtolt, Evans's partner in Yacht and 5 Every Day, in an interview with Artbound. "Claire and I are both eternal optimists, as is Tom, so we like to see the best in everything, and imagine that everything can reach its full potential."

Paul told me that he thinks there is a perfect storm for the latest resurrection effort to stick. "A lot of what [Young] was trying to accomplish 40 years ago is in the zeitgeist now, and furthermore the technology is available now, and it seems that it speaks to a new generation of people," Paul said. "This park is a ghost town, but I think that's going to change, because they just redid Grand Park, and with everybody moving [to] downtown, it's just a matter of time before this area is reactivated."

Evans, who was an editor at science fiction magazine OMNI Reboot and the Futures Editor at Vice's technology magazine Motherboard, laid out the Triforium Project's plans for the Triforium. "One of the problems [with the original Triforium] was that the computer system was an extremely specialized system that the city just wasn't equipped to maintain," she said. "We're going to try to build a system that is as nimble and adaptable as possible. We're in a position now, in 2015, where we have much more inexpensive, updatable, networkable computer systems that we can put in there. So we want to build a new brain -- a much simpler, smaller brain. We want to replace the incandescent bulbs, which are constantly burning out, with an LED lighting system that will last longer and be more efficient, and it will also be much more flexible in terms of programming."

The Triforium Project team have plans to collaborate with programmers and artists to create software platforms that allow Angelenos to interact with the public artwork online. "We think interactivity in 2015 is a very different thing than it was then, and we have an opportunity to make people feel creatively invested in this thing, and to make them feel like it's an instrument that all Angelenos can play," Evans explained. "So we want to build an awesome web system for people to create, and they can even maybe play games on the Triforium."

Young passed away in 2007, but his daughters assured the crowd that he would have been ecstatic at the use of modern technology to update the Triforium, especially after seeing it fail for so long, both in its technological shortcomings and in the eyes of the Los Angeles arts community. In 1977, according to the website Public Art in L.A., an art consultant wrote a letter to the Los Angeles Times claiming that the Triforium was "universally despised by every member of the Los Angeles art community." The writer went on to wonder why the city didn't just buy a Henry Moore or Louise Nevelson sculpture for the nearly million dollar price, plunk it down, and wipe their hands if they needed a piece of public art so badly. "He's been quoted as saying things like it was the great sadness of his life, that it was such a boondoggle," Evans told me. "He took that disappointment with him to the grave. I wish he was still around to see this."

The reevaluation of the Triforium is long overdue. It was a piece so far ahead of its time that technology has only now caught up with its original plans. It pissed people off, and had myriad problems, but what great work of art hasn't? At the event, Paul recited a particularly poignant quote from Young that outlined his hubristic spirit. "Yes, it will ruffle the feathers of many purist devotees of the specialized forms of architecture, art, and music, but since when was a creative artist ever afraid of cultural taboos?" said Young. "Being an iconoclast goes with the territory."

Leslie Young echoed her father's ambitions. "He had grander plans for it, and he wanted it to become the emblem for Los Angeles as the Eiffel Tower is to Paris," she told the shivering crowd gathered around the sculpture.

What makes the Triforium intriguing in 2015 are the precise things that made it so maligned when it was unveiled in 1975: its ambition, its eccentricity, its combination of art and technology. And for that alone, the Triforium is deserving of attention.

Apart from Young's daughters, Carroll, Evans, Bechtolt, and Paul, the Triforium Project team consists of Qathryn Brehm from Downtown Art Walk; Collective Studios, founded by Maria Redin and Lou Pizante; Tanner Blackman from the Do Art Foundation; Yacht's management at the Windish Agency; and Councilman José Huizar. In February, a full crowdfunding campaign will launch on Kickstarter, who has also pledged support for the project.

Dig this story? Sign up for our newsletter to get unique arts & culture stories and videos from across Southern California in your inbox. Also, follow Artbound on Facebook, Twitter, and Youtube.