These Artists Are Remixing the Superhero Genre to Center Black Stories

"Murderer!!" cries Ebon, as he lifts his nemesis above his head. "You killed my mother! And now… you, too, will die!" This scene from a never-before released second issue of America's first Black titular superhero Ebon turns to color on a digital screen. Every page of the original penciled and inked issue is framed and new action figures are displayed in transparent cases. In the adjacent room, a floor to ceiling rendition of Luke Cage fills an entire wall, MLK is reimagined as a superhero and W.E.B. Du Bois is paid tribute in an image of a blue fist jutting out of a comb labeled "Black Kirby" with the speech bubble, "We not just conscious… we double conscious."

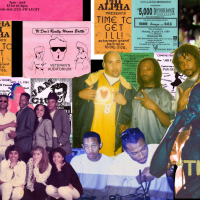

Two exhibits at UCR Arts, "Black Kirby X: Ten Years of Remix and Revolution" and "Ebon: Fear of a Black Planet" (March 19 to June 19), highlight the digital artwork of Afro-speculative trailblazers John Jennings, a professor of Media and Cultural Studies at UC Riverside and Stacey Robinson, professor of Digital Arts at University of Illinois at Urbana Champaign, as well as underground comix pioneer Larry Fuller, the original creator of Ebon.

Jennings and Robinson joined forces ten years ago to form the creative duo Black Kirby. Since then, they've collaborated on everything from graphic novels to art installations and even dance projects. Concepts from hip hop like sampling and remixing play a large role in their aesthetic, which combines Afrofuturism with the superhero genre to imagine alternative worlds that center Black stories. Their moniker Black Kirby is an homage to Jack Kirby, the founding artist of Marvel and one of their own childhood heroes.

Jennings first came across Larry Fuller's comic book Ebon several years ago while conducting academic research. Though Ebon was a groundbreaking piece of work when it was published in 1970, low sales in a primarily white market led to its discontinuation after only one issue. Recognizing its potential, Jennings reached out to Fuller, and the two began to collaborate on building out Fuller's vision of Ebon's universe. The groundbreaking products of these three comic book visionaries can now be viewed at UCR Arts.

John Jennings and Stacey Robinson Are Black Kirby

Growing up in rural Mississippi, Jennings spent his nights stargazing and speculating about worlds beyond the earth. Bullied for wearing secondhand clothes and possessing more brains than brawn, he felt an immediate affinity for Daredevil, an underdog who constantly strove to better himself. Jennings' mother, an avid science fiction reader herself, introduced him to the genre which would become a major focus of his future work, eventually landing him a Hugo nomination and two Eisner Awards.

"When I first started engaging with science fiction, it was probably more escapist, and now I feel like it's more utilitarian," reflects Jennings. "It's a way that you can actually talk about issues."

Jennings met Robinson on the comic circuit in 2006 while they were both living in Illinois.

"I prayed for John," says Robinson. "Seriously, I remember I was in church one day. I was like, 'God help me figure out this stuff that's in my head,' and then literally I met John."

When we say hip hop influences, we're talking not necessarily about a particular song, but an epistemology, a way of moving through the world that is connected to a culture.John Jennings

Two years after their first meeting, Jennings and Robinson found themselves alone on stage at an overbooked comic convention.

"For eight hours John and I just talked and talked," recalls Robinson. "We showed each other our work, and we had so much in common. So we were like, 'Yo we should experiment working together,' and that turned into Black Kirby."

The two became long-term friends and collaborators, and Robinson even followed Jennings to the University of Buffalo in 2015 to earn his MFA in Visual Studies under Jennings' mentorship. The same year, the duo published "Black Kirby: In Search of the MotherBoxx Connection," a collection of their visual artwork inspired by Jack Kirby, Black speculative fiction and hip hop ("Fear of a Black Planet" [the name of one of the current Black Kirby exhibitions] is in fact the name of an album by Public Enemy) .

"Hip hop is a culture, and rap music is only one aspect of it," explains Jennings. "You have sampling and remixing, graffiti, break dancing and MCing. When we say hip hop influences, we're talking not necessarily about a particular song, but an epistemology, a way of moving through the world that is connected to a culture."

Remixing plays a large part in Black Kirby's artwork, which combines Marvel superheroes, Black historical figures, Ghanaian adinkra symbols, bible verses and hip hop lyrics to reclaim culture and history and envision them in terms of contemporary ideals. One of their characters, Major Sankofa, derives his name from a Ghanaian word that means, "go back and get it."

"A remix visually is just a collage," says Jennings. "And by remixing it, you're changing it. You're making it your own, but you're also paying homage to the old thing."

One of Jennings' favorite pieces in the show is The Mighty Shango, a digital collage that reimagines the Norse God Thor as the Yoruba God of thunder. Another character that Robinson likes is Mo'Blacktus, a riff on Galactus, who absorbs the energy of planets in order to survive. Black Kirby's large-scale poster invites viewers to question how they visualize God.

"If that person were coming to Earth as a giant white man, you would look at him as a God, right?" asks Robinson. "Well, what happens when that's a giant Black man coming to bring justice to Black people? That's one of my favorite pieces because God has a gold grill in it, because God wants to be fresh too."

Deconstructing Race with Black Kirby

The construct of race is a recurring theme in Black Kirby's work. According to Jenner, race can be viewed as its own mythology, a way to separate a single species into different groups based on arbitrary physical differences.

"Race is made up; it is science fiction," says Jennings. "It's not fixed. It actually updates itself, changing according to geography, according to culture."

For example, due to the American concept of the one-drop rule, a person in the United States who has both black African and European ancestry will likely be coded as Black. However, this same person placed in a Black majority country might very well be coded as white.

The categories of race can also change throughout time. For instance, Jews, who are often considered white today, were not considered white for most of the 20th century. Even Italians were considered too dark-skinned to be white until the 19th century. In the United States, the ideas of racial identity have long helped to legitimize discriminatory immigration policies as well as institutions like slavery.

Jennings hopes that his artwork sparks conversations about how Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.'s dreams for the United States can be achieved. "I'm a teacher and a maker, and so I'm always trying to make people comfortably uncomfortable because you learn things when you're a little bit outta your depth," says Jennings.

"I want Black people to think about themselves in the future and then build a future that we want," adds Robinson, who emphasizes the importance of listening to the elders. "But before we can even converse about those ideas, we have to create imagery that shows us in future spaces."

While Jennings embraces the term Afrofuturism to describe his work, he considers the term Afrospeculative to be more accurate. "It's not just about sci-fi and futuristic ideas. It's also about the esoteric strangeness of the every day," he says.

For Black Kirby's own future, the two are already working on an art installation project for Boston University, new graphic novels, and ideas for an exhibit that celebrates Black women. Their extensive projects have led them to create MotherBoxx Studios, a collective that includes other comic book artists working on their own projects.

"Black Kirby will go on forever," says Robinson.

In terms of his impact, Robinson hopes that the exhibition inspires everyone to share their own story.

"I'm telling my story, the Black story. I'm not telling your story," says Robinson. "But guess what? We need more stories about Asian girls who eat cookies and save the world with sidekick puppies. It could be as obscure as all those things, like I want to read that. So come and enjoy our show, but tell your own story too."