This Is Slick: A Conversation with Graffiti Writer/Clothing Designer Slick

The Pharcyde's debut album, Bizarre Ride to the Pharcyde, celebrates its 20th anniversary this year. It remains a seminal moment in hip-hop, especially coming out of Southern California where Bizarre Ride's twisted sense of humor and unexpected vulnerabilities contrasted with the bulletproof bravado of L.A.'s gangsta rap aesthetic. As part of the 20th anniversary celebration, the album's label - Delicious Vinyl - has rolled out a series of box sets, including a 3-CD reissue and a 7-7" single reissue.

Prominently featured in both is the album's indelible cover art, which, on first glance, is an illustration of the Pharcyde's members riding a rollercoaster car into a razor-lined Tunnel of Horror. It's only when one looks at the cover's - pardon the pun - full spread, that one realizes the group is actually rolling into a vagina dentata. Bizarre ride, indeed.

The artist behind the cover was Slick (né Richard Wyrgatsch II), a then-20-something graffiti writer/fine arts graduate from the Art Center College of Design. Slick went onto become one of the most dominant street clothing designers out of L.A., with brands like Fuct, Shaolin Worldwide, and now, Dissizit, as part of his prolific portfolio. KCET ArtBound's Oliver Wang recently sat down with Slick in his Gardena design studio to talk about his early rules to graffiti, working with Ice Cube, Boo-Yaa T.R.I.B.E. and Pharcyde, and why his iconic "L.A. Hands" don't belong to a certain mouse from Anaheim.

Oliver Wang: You've lived in L.A. for over 20 years but you're originally from Oahu, yes?

Slick: Yeah. I always say I was born and raised in Hawaii, but it seems more like I was raised in L.A. 'cause I've spent more time in L.A. now.

OW: Is Hawaii where you first got into street art?

S: I was attracted to pop locking. I saw the older kids doing it and I was like, 'Damn, that's dope.' You know? But I was always into art, before that, whether it's painting or drawing with my mom. So when I got into the dancing and the music [and] ended up hooking up with a crew. I turned out to be the worst dancer in the crew, especially when b-boying came into the picture. I could pop, pop lock, but when the heavy, power moves, acrobatic shit came in, I just wasn't an athlete. So I just put more to the art. I was more on the creative side with my hands, so naturally, I took up the can.

OW: How did things like hip-hop, be it the music or dance or style, arrive to Hawaii, especially being so isolated from the mainland?

S: Looking back, I believe it's due to the heavy military [presence]. The military would come from the East Coast or whatever, so the popping clubs would be on military bases. The big thing, for me, as far as my step into the graf world, was Style Wars. We were already messing with graf, but not to that extent. And when we saw it and recognized [graffiti writing] was a whole culture. It set up the rules for us.

OW: Rules?

S: I became a real aerosol purist. Everything had to be from a spray can. You couldn't even use roller paint. To me that was like cheating. It's like these silly rules that you put in your head, and it's so unlike now, where everything goes. If you used a stencil, or a stencil tip back then, you were like laughed at, you were like a big joke. And now because of Shepard Fairey or Banksy, whatever, it's accepted. But we were such purists, it had to be from the can, and if you couldn't hit a straight line, then you were just wack. You don't use cardboard to hit the straight line.

OW: You originally moved out to L.A. to attend art school, first Otis, then Art Center. But you stayed writing graf too?

S: The funny part is, I came out to L.A. to stop doing graffiti. But Otis is actually where I met my crew, K2S [Kill 2 Succeed], over there at MacArthur Park.

OW: To what extent did your background in graffiti influence what you were thinking about and doing in art school? And vice versa?

S: I was so into the graf, even when I was trying to leave it alone, my [school] projects and everything always went back to graf. I always tied it in somehow. But I think at Art Center, I learned how to see: chiaroscuro and reflective light. So that stuff started showing through in my graf work.

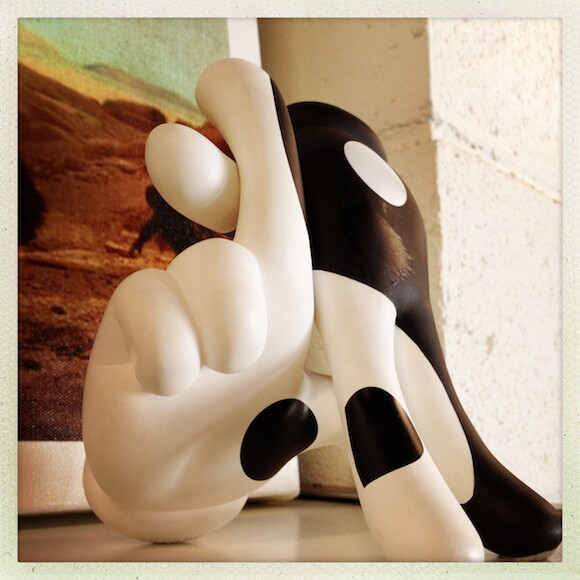

OW: One of the more iconic images you're known for are the "L.A. Hands" which proliferate in your both your graffiti and clothing designs. Because they're this pair of white-gloved hands, I immediately think of it as a riff on Mickey Mouse, especially here in L.A. Was that your source of inspiration? To riff on Mickey, give him a little gangster touch?

S: Everyone calls it Mickey Hands, but they were never Mickey Hands. And even Disney knows, because we registered the trademark, now, and they didn't even try to object or nothing.

OW: So wait, where did that idea come from? The idea of doing gloved hands?

S: It comes from when I used to mime, back in the day, you know?

OW: You mimed?

S: Yeah. [laughs] My mom used to work in a mall, right? And I remember one year in particular, there was a mime that used to work at the mall. And to me, it was kind of like popping. So I would [create] little moves and I'd use 'em in my popping routines and shit. And then I was a big fan of Shields and Yarnell. So that's where the gloved hands [came from], more so than the Mickey thing.

OW: In terms of your work with musical artists, your first connect began back in Hawaii, through the L.A.-based, Samoan rap group, Boo-Yaa T.R.I.B.E.?

S: They used to come out to Hawaii and battle everybody. And they used to tell me, "Slick, when you come to LA, come check us out." So they were the first ones I looked up when I came up here, and they treated me like fam, right from the get. I actually ended up doing their [art work].

OW: You also ended up creating a major wall piece for Ice Cube's "Who's the Mack?" video. How did that come about?

S: Me and Hex were having all these battles back then. And one of the people going to watch these battles was a director [Alex Winter], and he loved what we did.

OW: In the video, you actually see someone literally spraying painting the piece together. Was that you? S: Yeah! I didn't even finish that piece, and then I remember the director wanting to finish, and do the scene, and Cube and all them were there, but I was like, "Yo, it's not finished! You can't shoot it!" I was still spraying up until the time they were going to shoot. [laughs] So ridiculous. OW: Around that time, you and Eric Burnetti of Fuct Graphics ended up partnering up and working on the Pharcyde project together. Did you already know anyone in the group?

S: No. I remember hanging out with a lot of guys like DJ Paul Stewart and they were affiliated with Delicious [Vinyl], so it could've been through that channel, I'm not sure. OW: We'll get to the album cover in a moment, but you also designed the Pharcyde's "Pissing Hydrant" logo, right?

S: Yeah. The commission was to come up with a logo and we came up with a bunch of different concept sketches. We were trying to put something ironic in it, where we just thought it would be funny, if, you know, dogs piss on fire hydrants, we'll make it opposite.

OW: Ok, so where the did the album cover design come from?

S: I think we were all just lit, or something, just around the table. I opened my mouth and said, "Let's do a roller coaster! And it's gonna be a woman and they're going into her pussy!" One of the guys in The Pharcyde said, "Let's make it Ebony Ayes!" That's actually who it's supposed to be, 'cause if you notice on her hair, there's like lights going down, that's supposed to be like her braids.

OW: And whose idea was it to ring the entrance with razors/teeth? S: Probably my ex-girlfriend. [laughs] No, I just thought of funhouses and things like that.

OW: But there's a tradition in art and literature around the vagina dentata...that wasn't deliberate?

S: Oh right. [laughs] Yeah, it could be like, relationships or something. Who knows, it could be reading into a lot of shit.

OW: Was there any concern around the image being too sexually explicit to use as cover art?

S: No, 'cause from the get, we already established how we were going to crop it in, and how it'd be real a real subtle thing. I like the fact that it was a slow read. It wasn't too blatant, you know. OW: Real quick...I worked a summer in high school up at Magic Mountain in Valencia and they have a giant wooden coaster there which the Pharcyde coaster looks vaguely reminiscent of. Did you use Colossus as part of your design inspiration?

S: Yeah, I got some pictures of that. It's not like we had the internet and computers back then, when you could just go on and go to Shutterstock.com. I really didn't know what I was getting into, as far as illustrating rails, 'cause I'd never done it before. And then I was painting rails for days and days. I finished it and then my boy showed me an illustration of this other dope illustrator who did a sick ass roller coaster, so I was like, 'Oh damn. I can't turn this in.' So I ended up changing it, and going in and beefing up all the rails and that's what took so long. And then, I remember halfway through, getting attacked by fire ants. My partner thought I was just high but I attacked by fire ants while I was spraying.OW: That was a fairly big commission in terms of visibility but after that, you didn't really do anything as high profile again. Why?

S: I realized for the amount of money to do that type of illustration, it was just a lot of work. Not saying that I'm lazy, but after it was done, it wasn't as fulfilling, I guess. And then, I think the clothing thing came into play, where I figured, well I can do one illustration and we can sell it and multiply it, you know?OW: Your career in clothing design is substantial enough to take up a separate column but I did want to to briefly touch on Shaolin Worldwide, which you and Jeff Hartsel started in the mid/late 1990s. I remember seeing ads for the t-shirts back in the day and always wondered if there was any connection to the Wu-Tang Clan given how both you and them were riffing on kung fu in a hip-hop context?

S: Our common sifu, [Shaolin monk] Shi Yan Ming, was actually good friends with the Wu. In fact, we went to some shoots with the RZA, and we got to meet ODB, and I actually did an interview with Shi Yan Ming and the RZA for MTV. But we never really did stuff with the Wu. But it was fucked up because we used to send Shi Yan Ming a bunch of gear, and then Wu came out with some graphics that were just like our shit. But instead of Shaolin, they put Wudang. Then we were kind of like mad at 'em, like "Fuck them, it's all about Shaolin versus Wudang!"

OW: How did Dissizit come about?

S: So Dissizit was after the Shaolin thing. Dissizit was actually, "this is it," like "I'm done with this shit." I was so burnt, already back then. I was toying around with the idea, when I first started, [to call it] Dissizslix ["this is Slick's"] 'cause I wanted a name that was so original that nobody had. But I kind of overshot it, where no one could ever pronounce it, or could get it mixed up with "dyslectic." So we switched it back to Dissizit.

OW: You said in the beginning that even though you were born in Hawaii, you were raised by L.A. Do you see your clothing design as having a particular L.A. style?

S: I never thought of myself as, or wanted to be branded a L.A. brand. But over the years, because of the L.A. Hands, I guess we've been marked. But it would be nice....to think people from all over the world can relate to what we do. And they do, in Europe, Japan. East Coast...[less so] but I don't know if it's 'cause their anti-L.A. L.A. Hands is definitely not a big seller in NYC. But it's funny, because now that we moved here, in the Gardena, Compton area, I've actually been putting Compton on some of my shirts, and that actually has that appeal to the East Coast because people know NWA and all that. If it's not like they're repping L.A., they feel okay, they can rock a Compton thing.

OW: What, no love for Gardena? Where's the Gardena shirts?

S: [laughs] I don't know if people have heard of Gardena.OW: You could start the trend.

Check out this video of Slick's wall piece riffing on the Delicious Vinyl logo.

Dig this story? Sign up for our newsletter to get unique arts & culture stories and videos from across Southern California in your inbox. Also, follow Artbound on Facebook, Twitter, and Youtube.