This Radical Model of Health Care Empowers Women and Trans People

Vireo, the groundbreaking made-for-TV opera, is now available for streaming. Watch the 12 full episodes and dive into the world of Vireo through librettos, essays and production notes. Find more bonus content on KCET.org and LinkTV.org.

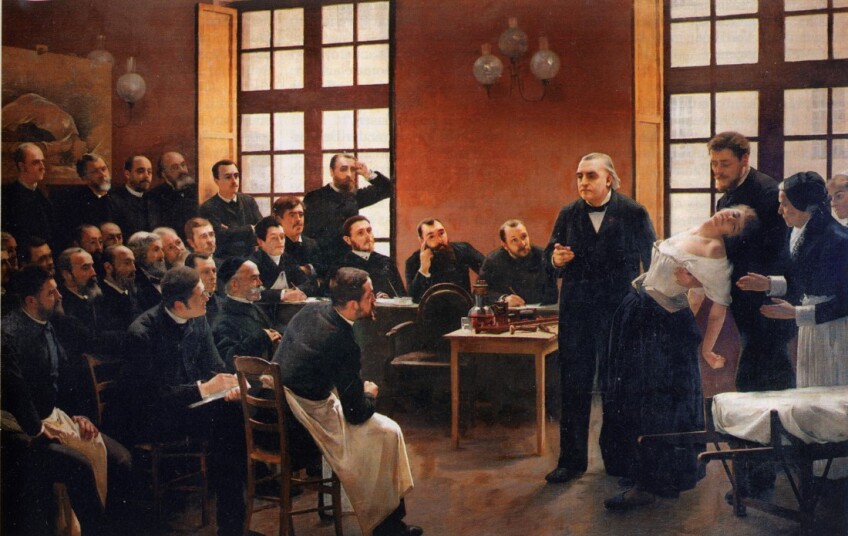

So often, when studying the nearly 4,000-year history of the diagnosis, "hysteria," I have wished I could time travel. I would suddenly drop unnoticed, camouflaged in proper attire and with cultural and linguistic aptitude, into any one of the untold number of places and times where so-called hysterics were said to exist in profound numbers. I would put my hand on the shoulder of that young woman standing next to me – the one found at Saltpêtrière Clinic in 19th-century Paris or the one accused of witchcraft in 16th-century Salem or the one in Persia in the Middle Ages or the one in Ancient Greece – and I would ask her: "Where does it hurt?"

That question, borrowed from civil rights icon and theologian Ruby Sales, is an open one. It is an invitation. In a 2016 interview with journalist and author Krista Tippett, Sales described the first time she was moved to ask the question:

A defining moment for me happened when I was getting my locks washed, and my locker’s daughter came in one morning, and she had been hustling all night. And she had sores on her body, and she was just in a state, drugs. So something said to me, 'Ask her, "Where does it hurt?"' And I said, 'Shelly, where does it hurt?' And just that simple question unleashed territory in her that she had never shared with her mother. And she talked about having been incested. She talked about all of the things that had happened to her as a child, and she literally shared the source of her pain.

If I could time travel, I imagine the answers to this question would include all the possible permutations of pains of the mind and the body; destructive relationships with family, partners, or friends; traumas, abuses, and violations of untold forms; displacement, heartbreak, loss, and the complicated hurt, or worse, of living in a world that systemically values some identities, beliefs, and behaviors more than others.

The voices of those most dearly impacted, the ones from whom I want to hear, are largely absent from the historical record. That's why extraordinary measures, like a time machine, are required. Instead we have had access to the ideas of any number of male physicians, clergy, and judges, a bounty of knowing individuals who diagnosed, sentenced, pronounced, declared, subjected, ostracized, committed, displaced, tortured and otherwise treated these women, in any number of ways.

Here it is important to interject that a substantial number of these experts must have believed that their theories and actions were of benefit to those who were diagnosed or to society as a whole. It is also important to note that there were men and gender-variant people who were treated as hysterics and witches for behaviors, ideas and practices that did not conform to the standards of the day. But overwhelmingly, those labeled hysterics and witches were women.

What it was all these people were suffering from, or whether they were actually suffering at all, we can never truly know. We can imagine any number of responses to the question, "Where does it hurt?" from "my neighbor says I killed her chickens" to "there is a soreness in my throat" to "I love women" to "I am hungry" to "there is a pounding in my chest upon recalling that night" to "my father put me in this place because I am a reformer living with my love out of wedlock." What was really happening behind all the descriptions of seizures and fits and collapses and various other rebellions of mind and body?

While reading the historical record, I cannot help myself. Various contemporary diagnoses pop into mind: postpartum depression, anxiety disorder, disassociative disorder, epilepsy, PTSD, and on and on. But the dangers of retrospective diagnosis – of using one's present-day understanding to reach back in time and evaluate these mediated voices, foisting upon them some present-day label – cannot be underestimated. Retrospective diagnosis is a tempting puzzle, but it is a distraction from the individual and her pain and her particular historical and cultural context.

There are good reasons to resist labeling those long dead, but also good reason to resist diagnosis with regard to those who are living. That is one of many lessons I have learned from my 26 years as a collective member at the Chicago Women's Health Center (CWHC).

As a young activist, I was drawn to CWHC because of its radical model of care. CWHC emerged in 1975 out of the women's health movement, which had forged a powerful resistance to paternalistic and damaging conventions within mainstream medicine. Some practices, including sterilization abuse and rampant unnecessary hysterectomies, could be traced directly to hysteria's early history. In its early years, CWHC's main focus was gynecology, but over the years, alternative insemination, outreach and education, counseling, primary care, and Traditional Chinese Medicine and other integrative health practices have been added to more fully address client concerns. Nobody is denied care and all services are provided to women and trans people on a self-determined sliding scale.

When I first encountered CWHC's counseling program, I was surprised to learn that its therapists largely avoid diagnosis. With its roots in traditions including Relational Cultural Theory and Client-Centered Counseling, the program began in 1989 and is committed to a feminist relational perspective. The feminist part of the feminist relational perspective recognizes the client as a whole person with individual experiences and traumas – who is also impacted by a host of other factors: gender, sexuality, race and ethnicity, spiritual and religious practices, immigration status and so on. And the relational part of the approach recognizes the counselor-client relationship as the core healing variable. That relationship is an agent of change that allows the client to experience what is termed "unconditional positive regard" in a warm, accepting, and non-judgmental space.

Tina Lee, the program's director, tells me that clients are informed about the model of care up front and many initially contact CWHC because they are drawn to this particular perspective: "They call us because they want a recognition of all those different systems of oppression. After appointments, many clients, especially trans clients and those from marginalized communities, express that for the first time, they felt fully seen, fully heard, fully considered, felt safer to be themselves." In addition, the majority of counselors integrate body-oriented approaches such as Somatic Experiencing Therapy or Sensorimotor Psychotherapy into their sessions, recognizing the growing body of research that shows the importance of addressing trauma through the body. If we have learned anything from the history of hysteria, it is that psychological trauma and the physical body are intimately connected.

But, why avoid diagnosis? As Lee explains, "If we see the client as the expert in their experience, as someone who knows their strengths and vulnerabilities and so on, how can we diagnose? The danger of diagnosis is that it can take us away from the person as a whole person and their experience and their trauma. The potential is that you start working with the diagnosis and not the person." People are more dynamic and changeable than diagnoses, which are traditionally not modified over time. And, as Lee notes, "so many diagnoses, like bipolar disorder and borderline personality disorder, are themselves very gendered."

Lee adds that there are times when diagnosis is necessary, for insurance purposes. And there are times when a client might request a diagnosis. "If a person feels a diagnosis would be helpful, then we talk about why it's helpful. We pull out the book [DSM or Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders] and look at it together. I will say, here are the various criteria, and the client can choose if they want the appropriate diagnosis documented." Lee adds, "I see my role with clients as a co-pilot. We are partners in this work."

This thoughtful approach of working with people, not diagnoses, is the culmination of generations of rethinking the legacy of hysteria. It is an antidote to a vast history in which some were deemed inherently stronger and wiser and therefore charged themselves with the passing of judgment on those deemed inherently weak and pathological. The choice of forgoing diagnosis reminds us that labels like "hysteria" or "witch" have blinded us to individual struggles and challenges. Such terms have been used throughout time as a means of discipline and control. They do not encourage us to bear witness to those sources of pain we might really have in common - the shared fears and injustices, systemic oppressions, and traumas.

Given that there are millions of voices no longer here to speak for themselves, voices that are mostly lost and disappeared from the historical record, all we can do is imagine the truths, personal and otherwise, that their answers to the question, "Where does it hurt?" would reveal.

Top Image: Maria Lazarova and Rowen Sabala in "Vireo" | Remsen Allard