Uncovering the Hidden Treasures of the LAUSD Archives

"What happened to all the silver serving sets that were given to South Gate High School all those years back?" This was the topic of debate among those who kept watch on every South Gate community function. Comprised of city officials, business leaders and those who "remember South Gate when..." this clique gathers at every neighborhood gathering. From the sidelines, they evaluate the needs of the community and reminisce; telling dirty stories and politically-incorrect jokes. There is a familiarity in this gathering of older sorts. Together, they built the city into what it is, sharing knowledge ranging from where the skeletons are buried to how to access the cleanest public bathrooms. At every city function, I gravitate toward the center of this gathering. They accept me. As the daughter of one of their own, I am freely admitted. They make certain that none of their rough and tumble language or perspectives of life and politics is censored on my account. For them salty language and irreverent comments are a sign of love and intimacy. I bask in their affection. On this particular October afternoon, the City of South Gate hosted its annual Family Day in the Park. Offering medical screenings and disaster preparedness kiosks, families from around the area gathered for a strange mix of safety and health education booths, carnival rides and food trucks; in the extended summer heat. Despite the whirlwind of activity before them, the topic of the day: cutlery--silver serving sets from the 1950's.

According to local lore, in the 1950s, Los Angeles Unified School District (LAUSD) employed home economics courses as a vehicle for graduating refined and competent young ladies, soon to be young brides. For years, young women rehearsed their domestic futures by learning to cook, care for children and properly set a table. Learning propriety and poise was such a priority that local department stores donated countless numbers of silver serving sets to be used in schools across the city. Retired South Gate High School History teacher, Clyde Putnam, claimed that the sets were so common that he believes "students took them for granted." To a large degree, students viewed these sets as no different from the stainless steel flatware found in the average Los Angeles suburban home. The rise of the Women's Rights Movement in the 1960s prompted educational institutions to question the necessity of such gender specific courses of study. By the 1990's, the California Commission on Credentialing had redesigned Home Economics into a field which could be parlayed into careers outside of the home like fashion design, nutrition and child care. Architects of school curricula had re-imaged the field and largely discarded the 1950s aesthetics of the Home Economics experience. With the changes, silver serving sets were allegedly packed away as relics of a former era. But in South Gate Park, the 'Old Guard' quibbled little about the shift in curricula, the question still stood, "What happened to the silver serving sets of South Gate High School?" Someone whispered that some of the silver had been found under the bleachers in the football field. Someone else wondered if, in the words of Elisa Doolittle, "Somebody pinched it..." "Well, Of course, somebody pinched it! I always thought it was Miss _____ and she died a few years ago but most likely, it was...the City!" declared one of the more crotchety gentlemen of the group. This did not mean the tiny City of South Gate but the City of Los Angeles. Like most of their conversations this one ended without a consensus, though it was agreed upon that if I wanted something to research and write about, this would be a fine and timely subject.

Though they often regale me with ideas to pursue and define my career by, this one actually sounded intriguing. Not only had I become fascinated with the fate of the silver serving sets, but I wondered if these utensils were as priceless as remembered. And, could "the City," the City of Los Angeles, have "pinched it?" To what end?

When I got home I Googled, "Silver Serving Sets" + "LAUSD." Nothing. Then I tried, "Silver" + "Los Angeles Unified School District." Still nothing. This meant that I needed to go back to the source -- back to the Old Guard. After sending a message of concern about needing more leads, a family friend told me that an archive housed the many valuables which once sat in Los Angeles schools. From there he knew little of this archive. Further research revealed only one article in the Los Angeles Times from 1998 entitled, "L.A. Schools Unearth Their Art Treasures." According to this article, LAUSD received millions of dollars worth of art and artifacts as gifts over the span of one hundred and fifty years. These gifts ranged from million dollar paintings of California landscapes by illustrious artists such as Maynard Dixon, to antiquities from the Classical Era. Over the years, graduating classes, alumni and teachers gifted fine art to their alma maters only to have these gifts forgotten in subsequent years.

Educational institutions are not designed to have long memories--curricula changes based on the ever-shifting gales of state and federal politics. Each year teachers are hired, retire or are reassigned. Administrators are shuffled about, students enroll and transfer almost daily, and every June another batch graduates. Gifts are given with honor and received with pride, but this exchange is only a shimmer on the institutional timeline. Ultimately everyone disappears except for the gift itself. Schools are built for progress, making the memory of gifts short. By the 1980s, rare paintings, books, and manuscripts laid forgotten, in little used closets and storage rooms across the city.

As I read about the existence of a rare books and art archive in the Los Angeles Unified School District, the looming question became, "Why would someone donate priceless art to their local public school?" In my mind, public schools were to be the recipients of plaques engraved with poetry or a sapling which would give shade to generations of future students. Priceless art should go to museums or fancy libraries -- never schools. I tracked down the Los Angeles Unified School District Art and Artifact Collection (Archives) online interested not in ogling the art pieces themselves, but curious of their origins. The website designated the space as open to the public every Friday with an appointment. Though this project began with a search for silver serving sets, it had now morphed into a larger query that interrogated the nature of Los Angeles itself. Did most cities have a legacy of housing priceless art pieces within the public schools and then forgetting their existence only to be once again unearthed and then properly housed?

I emailed curator, Leslie Fischer, requesting an appointment. Her response was surprisingly wary. "I would recommend that we start with a phone call and see if it makes sense for you to come in," she wrote. I am accustomed to making appointments with archives and visiting at my earliest convenience; instead, I needed to justify my interest. This wariness to discuss the matter of fine art once housed in LAUSD schools pervaded those involved with the LAUSD Art and Artifact Collection and its creation. After locating a prominent artist and photographer associated with finding art pieces and rare artifacts around the city in the 1990's, I sent a very hopeful and prematurely thankful email regarding my research and requesting time to discuss the endeavor. A day later I received a response with the subject line, "Ancient History." Within the email he informed me that he and a number of others founded the LAUSD Art and Artifact Collection in the 1990's and that too much time has passed to further discuss the politics or experiences surrounding the project. He also claimed that some of his former colleagues had passed away and he did not find it proper to share their names. There was also an implication that the experience was an arduous and painful one which need not be revisited. His email concluded with an in-depth description of his current projects which he was willing to discuss further via email. Beyond that he was sorry to be so unwilling to assist me. After reading his email I began to reflect upon my work as a historian. In essence, historians work with the dead and overall, they are a pliable and accommodating demographic, unlike the living.

Without an outside lead to discuss the art archive and collection, I emailed Ms. Fischer and conveyed the following message, "Dear Ms. Fischer, I recently met with a number of family friends and while together they shared that once upon a time valuable silver serving sets were donated to a number of LAUSD schools They went on to communicate that the district has an archive of valuable art and collectibles which serves as a depository for the rare art holdings historically found in the city. It is not my interest to disrupt the workings of your archive. I merely have an interest from the perspective of civic memory and legacy." After waiting a few days for a response, I received a message complete with an appointment two weeks in the future.

The Los Angeles Unified School District Art and Archive Collection is located in the LAUSD Police Headquarters. Like any police station in any urban metropolis in the U.S., it is a depressing gray building surrounded by metal bars and a fence. The only way to enter the building is to press the button on an intercom and state your business. At first the guard assured me that no art archive existed in the building. I told him it did. I then stood in silence outside the station while he checked his files. It started to rain. The door buzzed open and the same guard and I had an identical conversation. With a little goading he checked his files, he called the operator, he put on his glasses and searched through a book. He took off his glasses and dialed another number. At last Ms. Fischer appeared. Though still seemingly wary of my presence she escorted me up the elevator and down a hall lined with the offices of active duty LAUSD police officers. On one hand, I found visiting an art archive in a police station to be bizarre and intimidating. On the other, I could not think of a better more unassuming place to house an art archive. In the halls of the police station she explained that there were plans to move the entire archive to another LAUSD office building and from there, hopefully a museum space would be constructed for the public. She also confessed that people did not often visit the archive except for research for master's theses and doctoral dissertations. Being an art archive in the age of budget cuts is not the easiest task; often she is required to justify its existence to the district. Some LAUSD administrators and city officials have even implied that the auctioning of the archive could alleviate fiscal strains. Remaining under the radar and avoiding questions regarding the existence of an art and antiquities archive in LAUSD has served as a mode of survival. The presence of a writer could instantly alter the safety of the archive as an institution. One poorly penned word could easily be disastrous and as a result, no press is often the best press for an office struggling to maintain itself.

I did not feel disappointed when I entered the art archive that I attempted to gain access to for weeks although there is really nothing romantic about the space. It was not like entering a hidden wing of the Getty. It is surely not the long lost cousin of the Huntington. The space is utilitarian with white walls and lined with file cabinets in two of the three rooms. The third room is filled with rows and rows of bookcases. Amidst the complete history of LAUSD curricula and ephemera stored in all those file cabinets are antique student desks, sturdy wooden bookcases with glass doors that were found in school buildings before being demolished. Retail furniture stores sell replicas of these same bookcases for thousands of dollars on La Cienega Boulevard. There is also an impressive collection of audiovisual technology from lectures gone by. Donated paintings and prints hang from the ceiling in wooden frames, which when hung together resemble a large binder protruding from the wall. Amidst the school posters, designed by students from across the district over the last one hundred and fifty years, hang the landscapes of early twentieth century California painters.

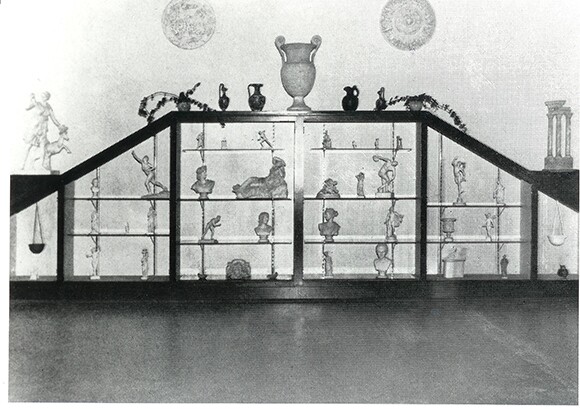

As we continued to tour the archive, other shelved pieces of the collection caught my eye; a tiny maquette or plaster model of the figures which were intended to grace a fountain in Pershing Square in the 1930's. The fountain was never built due to a lack of finances. Beside the maquette stood a shelf lined with gray boxes. Within these boxes is the LAUSD's Antiquity Collection. Donated by Venice High School's historic and now defunct Latin Museum, this collection is the most valuable aspect of the district's Art and Artifact Collection. Largely collected in Italy and Greece by Edward Clark, a former principal of Venice High School at the turn of the twentieth century, the Antiquities Collection is a product of innovation and experimentation which later came to define Southern California.

The work of Principal Edward Clark has left an indelible print on the history of Classical Education in the city of Los Angeles. By founding the Latin Museum in the 1930's at Venice High School, the Los Angeles Unified School District became the benefactor of a wide range of antiquities including Roman and Greek coins, Mesopotamian tablets, Egyptian amulets and a plethora of other items that came directly from the Middle East and Southern Europe in the 1990's. Mr. Clark was not a native of Los Angeles though his passion for the Classical era continues to benefit the education of LAUSD students. Born in 1868 in Tallmadge, Ohio to a family of educators, Clark ultimately stood above other faculty and educators in his effort to fully understand the Classical Era. Early in his career, he began traveling to Southern Europe and purchasing antiquities for both his private collection and for classroom use. While a professor at Ripon College in Ripon, Wisconsin, he purchased over one hundred antiquities including Roman oil lamps and Greek and Etruscan urns. In an interview with Ripon's, College Days newspaper, each of his purchases were "pronounced genuine by the men who know." Purchasing antiquities in Greece and Italy and bringing them home was not uncommon during the turn of the twentieth century. Today the transport of antiquities around the globe is an issue fraught with scandal and is associated with words like, looting and destruction. But, in the early twentieth century, the purchase of antiquities stood as a cherished aspect of European travel. Flea markets across Southern Europe sold off pieces of the past for a range of prices. Some local people even offered travelers the option of paying them to dig up antiquities by the hour. Whatever was found during their contracted digging time belonged to the paying tourist. It was not until 1939, under the regime of Mussolini, that cultural patrimony was declared. Under the 1939 law, "Regarding the Protection of Objects of Artistic and Historic Interest," antiquities were declared to belong to the state, even those found in private Italian homes with the goal of maintaining the heritage of Italy's past.

In addition to purchasing antiquities, Clark took hundreds of photographs of Greek and Roman ruins and noted travel destinations across Europe. When he presented his collection to his students at Ripon College and small communities across the Midwest, the experience likely represented the closest many small town Midwesterners would ever come to the ruins of Italy or antiquities of Greece. Edward Clark quickly became a local sensation. At times, people numbering over a thousand, filled darkened lecture halls and auditoriums to hear his lantern slide lectures and see images of his travels.

In an age of television and streaming media, its difficult to fathom that a lantern slide lecture could draw hundreds of people. But lantern slide presentations, or Magic Lantern Slide Shows as they were called at the turn of the twentieth century, stood as a modern marvel. In order to achieve the brightest image possible, projectionists attached slide projectors to oxygen tanks, inserted a pellet of lime behind the projector's lens and then lit the limelight pellet on fire. The oxygen in the tanks would then feed the flame. A brilliant white light illuminated any photographic slide in the brightest known resolution of that day. Projectionists not only had to manage the shifting of slides as the lecturer presented, but he also needed to perfectly balance the amount of oxygen fed into the flame to avoid either dimming or an infernal catastrophe. Magic lantern slide lecturers, like Clark's, drew thousands of people because their personal photographs could be projected to an average of a 12-foot square. For audiences, it seemed to be to scale of major travel destinations like castles and promenade scenes. Edward Clark's lecture stood as the Victorian version of the IMAX experience. His talks became so popular that they received special coverage by the Chicago Daily News.

But for Clark, the accumulation of antiquities and the capturing of photographic images of the ancient world balanced the Spartan curriculum of Classical Studies. It was his opinion that the learning of the Classics could only be truly successful through the usage of the laboratory method. As students and the general public saw the images, he simultaneously conveyed their stories. In accordance to the laboratory method, if a student holds a relic or an artifact in her hands and hears the name of the piece in Latin, complete with an explanation of the piece's history, a lasting understanding is ensured.

Edward Clark left Ripon College and his Midwestern lantern lecture tours in 1910 to head the Italian branch of the Bureau of University Travel. He remained in that position for five years until he was most likely forced to shut down his office as a result of World War I. There is little information regarding his whereabouts or activity during the early years of the war. At 46 years of age he was just shy of the draft age- capped at 45. Too old to serve and without any known records, his years between 1915 and 1917 are completely unaccounted for. But in September of 1917, Edward Clark was announced as the new principal of Venice Union Polytechnic High School. The migration of Edward Clark to Southern California is not a complete mystery. Between 1910 and 1920, hundreds of thousands of people moved to the Los Angeles area. Lured by the rise of major industries like oil, agriculture, shipping and entertainment, both the intellectual elite and the common worker flocked to the area in search of prosperity, comfort and an amiable climate. The city of Venice reflected Los Angeles' spike in population growth but held its very specific character. Laying a bit more than fifteen miles outside of downtown L.A. and accessible by electric trolley, the city of Venice distinguished itself as a resort town offering a wide range of amusements including rides, a grand pier and architecture reminiscent of Venice, Italy, complete with a canal system. It is not difficult to understand why Clark chose to reside in this growing community dubbed--'Venice of America.'

Clark's 1917 arrival in Southern California reflects another trend. As turn of the century Los Angeles drew the talents of daring yet controversial figures like Edward Doheny, Abbot Kinney and William Mulholland, the L.A. area lured other prospectors and innovators of all stripes. Clark arrived with his antiquities and convictions regarding the laboratory method, as a larger wave of artistic seekers pinpointed Southern California to be a most excellent environment to push the envelope of art. Artists such as Dana Bartlett (1915), Paul Lauritz (1918), and George Bickerstaff (1922) arrived in search of something new. These artists from Europe, the Midwest and the East Coast flocked to California for the weather, the liberality and the light; thus creating California's version of an Impressionist school of art--the California Plein-Air style. Paul Lauritz came from Norway after World War I and captured the gray, white, starkness of California mountain ranges in the winter while George Bickerstaff arrived from Arkansas to ultimately depict tucked away places like the San Dimas Canyon in the twenties. Dana Bartlett and Hanson Puthuff captured the beauty of California in their own signature fashion. As these men reinterpreted people's image of Southern California, Clark arrived at Venice Union High School with his artifacts, antiquities and a desire to innovate the teaching of Latin. Once more he employed the laboratory method in the curricula of Latin and the Classics were radically altered in the Los Angeles area. The man esteemed by the Chicago Daily News for his lantern lectures integrated the same techniques of allure and wonder to teach local high school students.

In 1932 the Classical League of Downtown Los Angeles showed their support of Clark's innovation in education and donated their collection of antiquities to Venice High School. With the assistance of a young instructor by the name of Martha Ward, Clark founded the Latin Museum. The oldest pieces of the collection were 4,000 years old. A sizable number of the ceramics came from the estate of Louis Napoleon, nephew of Napoleon Bonaparte. Records are unclear as to which pieces originally belonged to Clark and which were donated by the Classical League of Downtown Los Angeles, but for decades the Venice High School Latin Museum stood as the crowning achievement of Clark's career. Even into the thirties, students continued to host fundraisers with the goal of sending Clark, Ward and other teachers on additional archaeological trips to further add to the school's collection. By the 1960's the Getty Museum requested permission to borrow the school's Etruscan ceramic collection in exchange for renovating some of the pieces damaged in the 1933 Long Beach earthquake. In the 1990's Edward Clark's collection of antiquities was donated to the LAUSD Art and Artifact Collection by Venice High School only to sit amidst the donated work of the above named esteemed artists of the California Plein-Air School. As a collection, these pieces have come to represent the divergent yet creative thinkers which defined Los Angeles during the early twentieth century.

Still, of all the components of the LAUSD Art and Artifact Collection, the antiquities of Clark and the Classical League of Downtown Los Angeles continue to have the greatest relevancy. In partnership with the University of Southern California, pieces of the antiquities collection are taken into LAUSD schools each week to provide students with a hands-on experience with ancient civilizations. Known as 'Handling Sessions,' local sixth grade students get the opportunity to interact with Roman and Greek coins, cuneiform tablets and rarer items such as strigils--dull, curved metal tools which Greek athletes used to scrape sweat and dirt off of their bodies after practicing their sport or competing. In many ways, the goal of alleviating boredom and detachment in the study of the Classics through the laboratory method has been maintained through Clark's collection. A grant from the USC International Museum Institute allowed many pieces of Clark's collection to be scanned through Reflectance Transformation Imaging. RTI technology allows students to view enhanced images of antiquities from the LAUSD collection. USC archaeologist, Lynn Schwartz Dodd explained that through RTI, students actually see more aspects of the collection than they do by handling it. Tiny details like inscriptions are made clear, whereas under regular circumstances students miss the finer details of the collection. Students across the city also have the opportunity to continue to explore the artifacts online long after the antiquities are returned to the archive.

After my visit to the LAUSD Art and Artifact Collection I realized that I never saw any records of silver serving sets. Though I hated to bother Ms. Fischer once more, I had to inquire about the articles which launched my research of the archive. She was kind enough to check her records and reported that nothing existed regarding the whereabouts or the existence of silver serving sets at South Gate High School. After such a long journey I could not simply forget my initial assignment, so I ventured to South Gate High School to see if any records of the serving sets existed there. The school librarian welcomed me into her tiny library with its terracotta floors and arched doorways. Year by year she took down old yearbooks and leather-bound binders filled with copies of the school newspaper starting in the 1940's. I settled in for a very long afternoon, hoping to find an article or a mention of the school receiving silver serving sets. After combing through a year's worth of articles regarding school dances and football games, I ran across the headline in the South Gate High School Rambler from April of 1958. It read, "SG Girls Take Second, Third Place in Table Setting Contest Held Recently." Within this article sat two photos with two teams of girls beaming behind elegantly set tables. The article went on the read that the girls fared well in a contest sponsored by May Company and Seventeen Magazine. With their Flower Lane silver sets and imported china from France, the South Gate High School girls of 1958 awed the judges with their buffet dinner setting with a baby shower theme. The third place win went to their classmates' table with a Valentine's Day-themed dinner party arrangement. After weeks of research that led me to trace the expeditions of Edward Clark, the political challenges of Ms. Fischer, and the technological feats of RTI, I chuckled, thinking how my work ended with such a trifle. Still, I was relieved that the feat of these young women confirmed the recollections of the Old Guard of South Gate, though I could not report of any records regarding the current whereabouts of these sets. Maybe they were right--"Somebody pinched it..." or maybe after traveling around the city competing in table setting competitions things were lost or left behind. Either way, I am sure I will have to tell them that as all historians, archivists and archaeologists know, many things of the past can go forever unaccounted for.

Dig this story? Sign up for our newsletter to get unique arts & culture stories and videos from across Southern California in your inbox. Also, follow Artbound on Facebook and Twitter.