That Perfect, Toxic Lawn: American Suburbs and 2,4-D

If you’re worried about the weed-killer glyphosate, a.k.a. Roundup™, you’re not alone. The herbicide is getting increasing critical exposure in the news — and on social media — as we learn more about its potential effects on the environment and human health. Roundup use is growing exponentially, so that concern is sensible. But there are other commonly used pesticides that don’t get nearly as much public attention, despite the fact that they’re significantly more dangerous to people and the planet. In this short series, we'll discuss five common pesticides whose ill effects on human health and the environment are demonstrably worse than Roundup's.

For the second half of the 20th Century, the grass lawn was nearly synonymous with Mainstream America. It symbolized comfort and leisure. It was a sign that the homeowner was affluent enough to buy all his or her food at the store and could dispense with the wartime Victory Garden tradition.

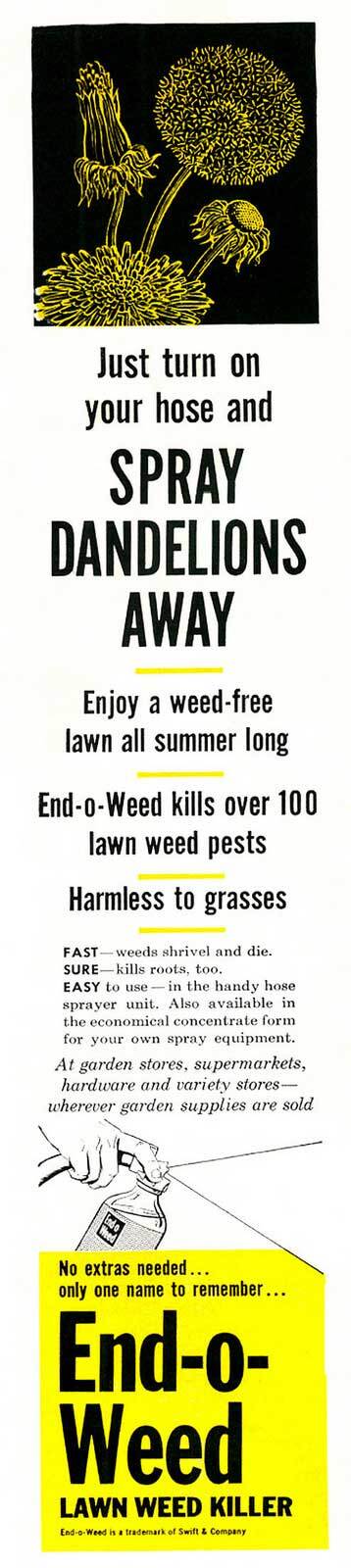

But not just any lawn would do: it had to be uniform. The tradition might have originated in the sheep pastures of British nobility, with a couple dozen pleasant species of flowering plants in the mix. But by the 1950s in North America, the idea of any other plant settling in among the Kentucky bluegrass or bentgrass was anathema. A handful of English daisies in a quarter-acre lawn meant a lazy homeowner. A dandelion even more so.

Before World War II, keeping your lawn “weed-free” was a lot harder, requiring never-ending physical labor to pull out the offending plants before they could go to seed. But wartime chemical weapons research solved that problem.

In 1945, the American Chemical Paint Company introduced its product Weedone, the first herbicide ever to hit the market that killed broad-leaved plants but not grasses. On farms, the weedkiller reduced the need for pulling weeds in grain fields, a godsend during the post-war labor shortage.

At home, Weedone killed dandelions, clover, plantain and other “weeds,” leaving turfgrasses uninjured. A uniform, weed-free lawn was at last within reach of the average household.

The active ingredient in Weedone was a compound called 2,4-Dichlorophenoxyacetic acid, 2,4-D for short. It had been developed by several separate teams of researchers working on secret chemical weapons projects during the war; the generals hoped to use 2,4-D to kill potato and rice crops, starving the Axis powers into submission.

That didn’t work: 2,4-D isn’t effective on those crops.

But the stuff did kill weeds in grass, and 2,4-D rapidly became one of the most-used pesticides in American society. After the herbicide’s patent expired in the 1960s other companies rushed to create their own formulations, often mixed with fertilizer in retail products called things like “Weed and Feed.” By 2005, the EPA estimated that around 46 million pounds of the weed-killer were used each year, about 30 million pounds of that in agriculture. Since then farm use of 2,4-D has only grown, reaching nearly 40 million pounds in 2013.

While farm use accounts for the majority of the poundage of 2,4-D used in the US, it’s in home lawns and gardens that the herbicide is applied most heavily, often at several times the number of pounds per acre used to kill the same weeds in farm fields. (Some of that difference is likely due to the fact that farm pesticide applicators receive some training in their proper use.) In several studies, 2,4-D was the most common herbicide found in suburban areas, and other studies have detected the herbicide in two-thirds of interior air samples taken from households. The herbicide breaks down in around a month in rich, moist soils but can linger indefinitely in other settings, for instance as a constituent of household dust. An Ohio study found 2,4-D in 98 percent of the homes tested, though just one of the homeowners reported having used the herbicide in recent weeks.

So what does that mean for public health? Critics of 2,4-D often make much of the fact that the herbicide made up about half of the active ingredient in Agent Orange, a weaponized herbicide used to defoliate farms and rainforests during the Vietnam War. Agent Orange exposure has been conclusively linked to serious diseases including many different types of cancer, Parkinson’s disease and other neurological disorders, spina bifida in children of exposure victims, heart disease and Type II diabetes.

But it’s a stretch to assume that 2,4-D is largely responsible for that list of horrors. Instead, toxicologists place the blame for Agent Orange illnesses on two other chemicals found in the defoliant: the herbicide 2,4,5-trichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4,5-T), and a common contaminant of 2,4,5-T with the unwieldy name 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin, a.k.a. “dioxin.”

That’s not to say 2,4-D is without its health concerns: it’s just that 2,4,5-T and dioxin are far worse. On its own, 2,4-D exposure has been linked, though not slam-dunk conclusively, to its own set of cancers, genetic damage, hormonal and immune system dysfunctions, and the usual range of pesticide-related irritations of skin, eyes, and lungs.

That slam-dunk certainty won’t arrive until regulatory agencies agree on how to classify 2,4-D. The EPA has steadfastly held that the herbicide is safe as used on the label. The National Institute on Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) lists several formulations of 2,4-D as known mutagens. Unusually for an herbicide, acute exposure to 2,4-D causes neurological problems, raising concerns that low-level, chronic exposure may do likewise. The International Agency for Research on Cancer, a division of the World Health organization, classifies 2,4-D as a possible human carcinogen, mainly due to the chemical’s ability to cause genetic damage. Exposure has been linked to low sperm counts and male reproductive damage in animals, as well as reduced litter sizes. Dogs who lay on lawns treated with 2,4-D have a significantly higher risk of developing cancers.

And that’s just 2,4-D, the “active ingredient.” The herbicide is generally sold mixed with other substances, classified as “inert ingredients,” which include things like surfactants (to keep weed spray from running off waxy plant leaves) and “preservatives” such as benzisothiazolinone, a broad-spectrum biocide. Many inert ingredients have their own health issues. And like its Agent Orange co-constituent 2,4,5-T, 2,4-D is often found contaminated with dioxin, an appallingly toxic chemical.

Human skin apparently absorbs 2,4-D much more readily when treated with sunscreen or insect repellent, and the effect is boosted if the human wearing that skin has been consuming alcohol. (If you’re planning to spend time on a lawn drinking beer in the sun with mosquitoes around, you might want to make sur that lawn has a lot of healthy dandelions in it.)

With all these potential health problems stemming from 2,4-D’s prevalence in the environment, you might conclude environmental groups have raised a fuss. You’d be right. In 2008, the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC) petitioned the EPA to ban 2,4-D. The agency essentially ignored the petition until 2012, when NRDC hauled the agency into court. In April 2012, the EPA denied the petition.

That’s important because of our old friend Roundup, a.k.a glyphosate, the notorious Monsanto herbicide that inspired this series. Monsanto — one of nine manufacturers of Agent Orange, back in the day — has propelled the use of Roundup to record amounts by selling genetically engineered crops that are resistant to glyphosate. Farmers can spray Roundup directly on those crops to kill weeds, and that has pushed glyphosate use well into the 200 million pounds per year range.

But all pesticides carry with them the seeds of their own obsolescence. As farmers spray Roundup on weeds, a few will survive and set seed. Their offspring get sprayed with Roundup, and the more resistant among them survive to set seed. Farmers spray more Roundup to kill the tougher weeds, which means the plants that survive are even more Roundup-resistant. A third season happens, and a fourth, and each year the weeds most resistant to glyphosate are the ones that survive and reproduce.

The result: farmers are now plagued with weeds that Roundup doesn’t kill.

Enter Dow AgroSciences, a subsidiary of Monsanto’s fellow Agent Orange manufacturer Dow Chemical. Dow has engineered GMO corn and soybeans that resist damage from Dow’s new herbicide Enlist Duo, whose active ingredients are a mixture of glyphosate and 2,4-D. Farmers struggling with roundup-resistant weeds may well turn to Dow’s Enlist crops, which will boost the amount of 2,4-D used on corn and soy fields. In 2014, the EPA approved use of Enlist Duo on GO corn and soy in 15 midwestern states. The agency is set to extend that approval to cotton this year, and to add 19 more states to the roster where Enlist Duo can be used.

And that raises the possibility that 2,4-D use could balloon the way Roundup use did in the last 15 years. In other words, even though Roundup may be the nation’s most-used herbicide at the moment, 2,4-D could well prove the longer-term danger to your health.

The other pesticides we covered in this series are the insecticide chlorpyrifos, the weedkiller atrazine, and the soil fumigants metam sodium and 1,3 dichloropropene. Banner: Lawn as Nature intended | Photo: Jeepers Media, some rights reserved