This Widely Used Pesticide Caused California's Worst Inland Environmental Disaster

If you’re worried about the weed-killer glyphosate, a.k.a. Roundup™, you’re not alone. The herbicide is getting increasing critical exposure in the news — and on social media — as we learn more about its potential effects on the environment and human health. Roundup use is growing exponentially, so that concern is sensible. But there are other commonly used pesticides that don’t get nearly as much public attention, despite the fact that they’re significantly more dangerous to people and the planet. In this short series, we'll discuss five common pesticides whose ill effects on human health and the environment are demonstrably worse than Roundup's.

On July 14 1991, a train derailed late at night along the Upper Sacramento at the Cantara Loop near Dunsmuir, California, spilling several cars into the first-class fly-fishing river. They included a tank car carrying metam sodium, the most widely used agricultural fumigant, which kills almost everything it comes into contact with.

By the time the sun came up and first responders noticed a leak in that tank car, 19,500 gallons of metam sodium spilled into the Upper Sacramento.

The result was disastrous.

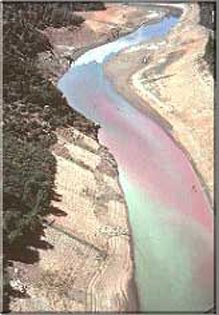

As the fumigant mixed with the river's water, it released a highly toxic cloud into the air. By the time that cloud had disspiated enough to allow emergency workers onto the scene, 38 miles of the river were effectively sterilized.

First came the larger animals. Fish floated lifeless to the surface. So did salamanders and crawdads. Countless smaller animals died un-counted. Within days, the plants and algae began to die off.

"At daybreak," wrote San Francisco Examiner outdoor columnist Tom Stienstra, "the smell was so noxious near Dunsmuir that it was difficult to breathe. A pea-green foam was running down the Sacramento River, and dead trout were everywhere, upside down, many on the bottom of pools, some floating. Under the rocks, the insect larvae were dead. Residents seemed confused but there was no doubt what was happening: A river was being murdered."

For the next two days, the plume of pesticide headed downstream at about a mile per hour. on July 17, that pea-green foam reached Shasta Lake, the main water supply for the Central Valley Project, which provides irrigation water for farms and drinking water for 10 million California households. Environmental agency workers were able to aerate the toxic plume, dissipating it into the air, so that contamination levels in the reservoir were below official safety standards.

But that didn't happen before the plume formed a 100-yard wide dead zone in the reservoir, three quarters of a mile long and 36 feet below the surface. At the bridge where Interstate 5 crossed over the plume, recalled Dunsmuir resident Ron McCloud, the California Highway Patrol was advising motorists to "roll up your windows, don't breathe, drive like hell and don't stop."

The damage was done. Not only did the wildlife in the river die out, but animals that depended on the forests along the river — bats, birds, and small predators like otters — lost their habitat. Many of them died. The toll on the river's fish, including the area's world-class rainbow trout fishery, was devastating. Millions of fish died. Millions of other aquatic animals died. Hundreds of thousands of mature trees died.

Though the river’s trout fishery more or less recovered within five years as fish repopulated the stretch from upstream, there are scientists even now, a quarter century later, who feel the river’s ecosystem has been permanently changed, the invertebrates and microorganisms that form the base of the river ecosystem permanently damaged by the 1991 spill.

Also permanently damaged by that spill: the respiratory health of people who lived along the river: local asthma rates spiked after the derailment.

That's what happens when you dump 19,500 gallons of metam sodium into the environment.

Terminology: herbicides kill plants, insecticides kill insects, fungicides kill fungi. Fumigants kill almost everything. And “pesticide” is a blanket term that includes all of the above.

In 2014, California industry used 4,142,910 pounds of metam sodium... on purpose. At 3.18 pounds per gallon in the most common formulation, that's almost 67 times more than was spilled into the Upper Sacramento in 1991. Nationwide metam sodium use in 2014 was around 38 million pounds of the stuff, about 612 Dunsmuir disasters' worth. That's just 2014, the most recent year for which metam sodium use statistics are available. From 1992 through 2014, American farmers and other applicators applied more than a billion pounds of metam sodium in the environment, according to a conservative estimate by the U.S. Geological Survey. That's more than 17,000 Dunsmuir spills.

Put another way: the Dunsmuir spill dumped a little more than 60,000 pounds of metam sodium into the environment. Individual farms will sometimes use more than that in a single season. This researcher documented a Yuma County, Arizona cantaloupe farm that used 75,000 pounds of metam sodium in a single application.

A potent biocide that works by breaking down into the highly toxic methylisothiocyanate, metam sodium is used as a soil sterilant to kill fungi and nematodes that might infect crop plants. That's mainly potatoes, but farmers also use the stuff to sterilize soils before planting bell peppers and tomatoes, especially where root knot nematodes are an issue.

Unlike atrazine or Roundup, there’s no real controversy over whether metam sodium is a carcinogen. Exposure to the fumigant has caused malignant tumors in lab animals. The fumigant's carcinogenicity is more or less established.

Before glyphosate use grew dramatically in the mid-2000s, metam sodium was the third most-used pesticide in the U.S. in terms of sheer poundage of chemical applied. By 2014, even with swelling use of glyphosate and a bit of a drop in metam sodium use at the same time, the fumigant was still the fifth-most-used pesticide in the US. Around 38 million pounds of the chemical were applied to farms in the US in that year — most of it on the West Coast.

The fact that metam sodium kills everything in the soil, which can then be planted with potatoes or other crops, might lead you to guess that the fumigant dissipates into the air after it’s applied. You’d be right. A study in the mid-2000s indicated that a significant number of people living in agricultural areas where farmers use metam sodium end up breathing in harmful amounts of metam sodium's main breakdown product, methyl isothiocyanate. As many as 100,000 Californians, for instance, were projected to be breathing air with unsafe levels of metam sodium in that study. Those Californians who happen to work on or near farms bear the brunt of the risk: there have been several instances in the last three decades of groups of dozens or hundreds of people falling ill after metam sodium applications in California. Even brief exposures can cause respiratory problems lasting for months.

Metam sodium doesn’t just cause cancer. Like atrazine, it’s a suspected endocrine system disruptor and a mutagen capable of causing birth defects and miscarriages. A 2004 EPA study of farm workers and pesticide exposure found that most ag laborers who must apply metam sodium are exposed to more than the cancer-causing threshold of the substance, even, in the EPA’s words, “with maximum use of protective equipment and engineering controls to minimize exposure.”

Metam sodium use, which grew in the 1990s as growers began to switch from the ozone-destroying fumigant methyl bromide, has dropped over the past few years. Part of that is likely due to the drought hitting the western states, which prompted farmers to grow fewer acres of potatoes — and which meant weeds weren’t as much of a problem. And some is due to use of other fumigants, such as metam potassium, whose US use grew from nearly zero in 1999 to 35 million pounds in 2012.

Nonetheless, metam sodium remains a threat to human health, especially to those humans who work on or near farms where the stuff is used. It won't show up as residue on your kale at Whole Foods, but the threat is real nonetheless.

The other pesticides we're covering in this series are the insecticide chlorpyrifos, the weedkillers atrazine and 2,4-D, and the soil fumigant 1,3 dichloropropene.