Financing Gay Liberation: How Local Government Supported LGBT Rights in 1970s Los Angeles

When many of us visualize postwar lesbian and gay activism, we think of gay pride parades, street demonstrations, and radical protests. These were certainly key ingredients to gay liberation, but in L.A. activists achieved much, much more. Transcending the grassroots, they entered the halls of local politics and showed how public resources could embolden gay power.

Transcending the grassroots, L.A. activists entered the halls of local politics and showed how public resources could embolden gay power.

This story was not unique to lesbians and gays. Around the same time, grants were utilized to fund racial justice centers, such as the Sons of Watts Improvement Association, the East Los Angeles Community Union, and the Chicana Service Action Center. Lesbian and gay activists – many of whom were also racial justice activists – connected their efforts to these struggles and sought similar financial support. “The question became,” one remembered, “how do we finance this revolution?” Possibilities emerged – quite unintentially – from the Nixon and Ford administrations’ urban initiatives, which were designed to empower local authorities over “big government.” This flexibility opened doorways to state resources for lesbian and gay Angelenos. Once they found an ally with discretionary grant power, the possibilities could be endless. In 1974 they found a partner in Los Angeles County Supervisor Ed Edelman.

Edelman was a new-age Democrat. He supported liberal issues like housing and union rights but also opposed the Vietnam War and endorsed Willie Brown’s Consenting Adult Sex Bill, which decriminalized sodomy in California. Upon his election, Edelman hired David Glascock as his liaison to the lesbian and gay community. In this role, Glascock brought gay concerns to political discussions and sought grant opportunities for fledgling activists.

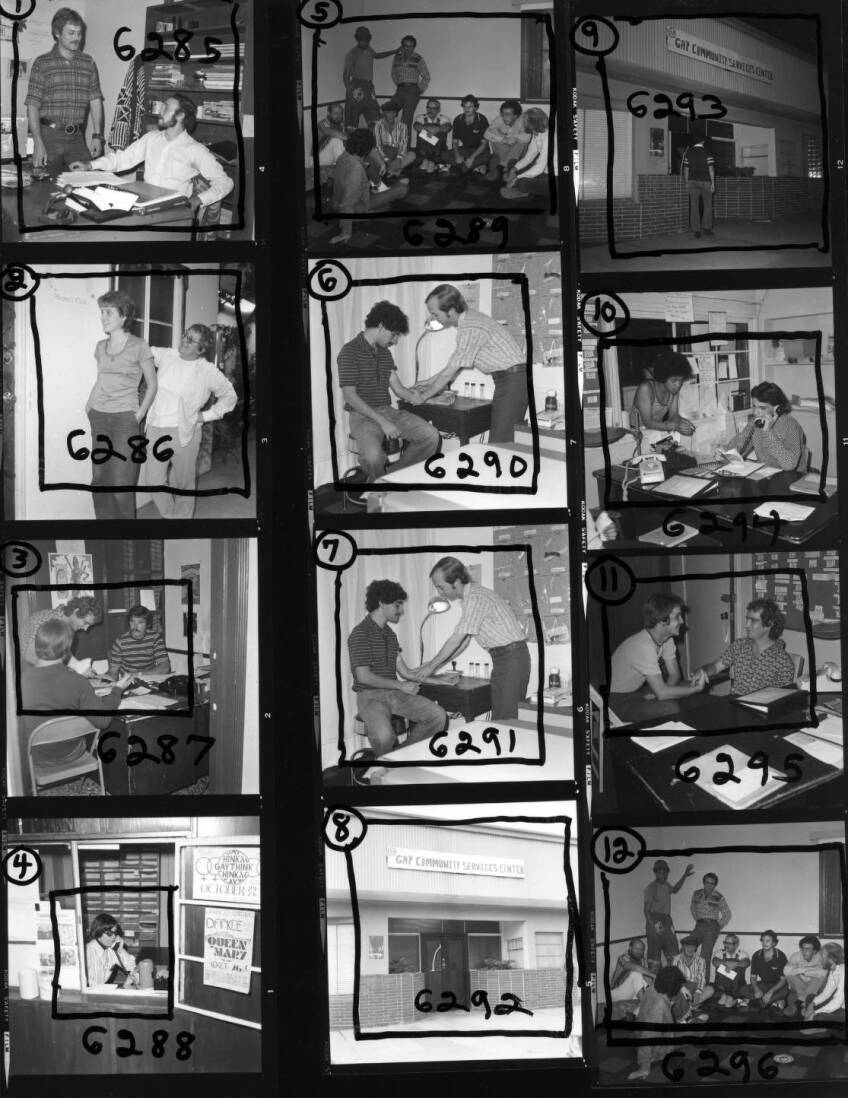

This was crucial to organizers of the Gay Community Services Center (GCSC), the first social service agency dedicated to lesbians and gays in the nation. By 1975, GCSC organizers were submitting county grant proposals on a regular basis. “Whenever we got requests we applied,” one organizer remembered. “Nobody else was doing that, but our government was supporting gays.”

Despite homophobic abuse from law enforcement, on the county Board of Supervisors lesbians and gays gained clout. When one agency representative refused to issue a grant to the GCSC, for instance, Edelman summoned him to his office alongside GCSC representatives. After a few minutes of excuses, he looked the man straight in the face and insisted he “just give them the money,” at which point it was all over and the grant was issued. In L.A. it helped to have an all-powerful county supervisor on your side. Indeed, funds secured from county grants allowed the GCSC to assist over 20,000 people with housing, employment, and healthcare programs. It was a clear sign that gay liberation had transcended the grassroots in L.A.

Of course, some accused the GCSC of “selling out” and “going establishment.” When I interviewed activists, they laughed at such characterizations. “Much like Mao Zedong and Ho Chi Minh,” one man explained, “we were part of a revolution that was fomenting. Providing services to the people could be a part of that. Revolutionary work didn’t involve just storming the barricades. It involved organizing people.” Another pointed out that in the early days of gay liberation, “we had been demanding a place at the table. Once we had it, there was no reason to stand outside shouting. We could change things from within.”

And change things they did. Despite bureaucratic obstacles, activists secured a steady source of public financing that brought needed social resources to their communities. More importantly, they forced social service agencies to incorporate lesbians and gays into anti-poverty initiatives and encouraged liberals to view them as a viable political constituency.

Why has this narrative been marginalized? As the 1970s gave way to the 1980s, a number of crises emerged that jeopardized lesbian and gay relationships with state and local government. In 1978, activists were dealt a hefty blow with the passage of Proposition 13 – the so-called Tax Revolt – which placed smothering restrictions on county coffers. A few months later, Proposition 6 – the infamous Briggs Initiative – threatened gay, lesbian, and transgender teachers. While voters defeated the initiative, the combined effects of these propositions left many conflicted about the government, anxieties which worsened amid the AIDS crisis. Fighting quite literally for their lives, many were enraged by the slow response from many state agencies. While Supervisor Edelman funneled millions in emergency funds to hospitals and grassroots organizations, it did little to diffuse the rage. As one openly-gay Edelman aide explained, although the supervisor was an ally, “he represented ‘The Man.’ He was on the county Board of Supervisors, and they weren’t doing enough. He was doing what he could, but he had to do more.”

Long before marriage equality, lesbian and gay Angelenos called on public resources and elected officials to support gay rights; they demanded – and received – a place in their own government.

Amid these titanic challenges, the nature of gay power transformed. Unable to rely on county grants and increasingly suspicious of the state, activists turned to friendly corporations instead. In so doing they ironically strengthened the ethos of privatization which fueled the Tax Revolt and austerity. In so doing many forgot that the state had once empowered gay activists and organizations.

What is to be gained from restoring this lost episode in L.A.’s gay history? Long before marriage equality, lesbian and gay Angelenos called on public resources and elected officials to support gay rights; they demanded – and received – a place in their own government. Public financing allowed them to house the homeless, employ the jobless, and heal the sick. The acclaimed historian John D’Emilio once explained that, within the gay movement, “if there is a place that seems like home and heart, it’s San Francisco. New York is mind. And Los Angeles is power and politics.” Understanding the source of that power is important and offers guidance to future activists. Most crucially, this forgotten tale of gay activism reminds us that the fates of gay rights and the welfare state have long been intertwined, and that both have a stake in each other’s future.

Further Reading

Baldwin, Ian M. “Family, Housing, and the Political Geography of Gay Liberation in Los Angeles County, 1960-1986” (Doctoral dissertation, 2016)

Bell, Jonathan. California Crucible: The Forging of Modern American Liberalism (Philadelphia: The University of Pennsylvania Press, 2012)

Faderman, Lillian & Timmons, Stuart. Gay L.A.: A History of Sexual Outlaws, Power Politics, and Lipstick Lesbians (New York: Basic Books, 2006)

Hurewitz, Daniel. Bohemian Los Angeles and the Making of Modern Politics (Berkeley: The University of California Press, 2007)