Forthcoming “People’s Guide” Unpeels Orange County’s Hidden History

Elaine Lewinnek: In 2007, the Santiago wildfires burned away undergrowth in the Santa Ana foothills of Irvine Canyon Ranch, revealing a plaque proclaiming that a California oak tree there was the lynching tree for two Mexican “banditos” allied with Juan Flores’s “gang” in 1857. Equestrians had erected this plaque in 1967, probably with the same sort of nostalgic frontier pride that Knott’s Berry Farm constructed a fake “hangman’s tree” in Buena Park in the 1940s – yet the plaque and lynching tree were then forgotten for decades, until the recent fires revealed it. This plaque is not only a symbol of racist extralegal violence, but also a marker of memory and forgetting, revealing the ways that interpretation of a particular place can shift over time, as the violence of 1857 and the designation of this tree in 1967 gave way to silence in the ensuing decades.

Like the wildfires that revealed that plaque, our book aims to clear away some undergrowth in the image of Orange County with the goal of spurring new growth and reinterpretations of the meanings of the past inscribed in the landscape.

Introduction: That book is the forthcoming “A People’s Guide to Orange County,” a follow-up to the 2012 publication “A People’s Guide to Los Angeles,” an effort by historians Laura Barraclough, Laura Pulido, and Wendy Cheng to deliberately disrupt the ways in which “Los Angeles is commonly known and experienced.” Too many stories had been ignored; the city’s full history obscured. “Los Angeles is filled with ghosts not only of people but also of places and buildings and the ordinary and extraordinary moments, and events that once filled them,” they wrote in their introduction. “History is literally embedded in the landscape.” The success of their endeavor inspired similar guides now in development by the University of California Press on nearly a dozen cities from Atlanta to Berlin – and nearby Orange County.

KCET’s Ryan Reft recently asked two of the Orange County guide’s authors – Lewinnek, a professor of American studies at Cal State Fullerton; and Thuy Vo Dang, an archivist with the Southeast Asian Archive and Regional History at the University of California, Irvine – a few questions about the project. Their responses below have been edited for clarity and length. The guide’s authors also include Gustavo Arellano, editor of OC Weekly; and Michael C. Steiner, professor emeritus of American studies at Cal State Fullerton.

Ryan Reft: Why is place is so important?

EL: As scholars, teachers, and activists, we have noticed the power of place to create collective memories. A decade ago, I showed my students a 1920s photograph of a citrus packing-house in Orange County, hoping to talk about gender and race relations within the local citrus industry, but my students surprised me by asking whether that particular packing shed was in Placentia or Fullerton. I had to double-check my own notes, because precise location had not seemed important to me: it was my students who asked me which intersection that photo was taken at, because some of them have relatives who worked in packing plants and all of them may pass these spaces in their daily lives. My students taught me that places have an incredible capacity to contain stories.

RR: Why a guidebook?

Academic terms like transnationalism become concrete when we start explaining a site like the “Caution: Immigrant Crossing” sign that was along the 5 freeway near San Onofre.

EL: Historians tend to focus on various sub-specialties … [and] are often segregated into their own sub-fields, though of course any given person may experience those histories together. A guidebook allows us to synthesize those disparate studies.

Academic terms like transnationalism become concrete when we start explaining a site like the “Caution: Immigrant Crossing” sign that was along the 5 freeway near San Onofre. That sign is not far from the place where the first indigenous Californian was baptized by the friars, where the last governor of Mexican California had his ranch house, where the Veterans of Foreign Wars kidnapped and tortured free speech activists in 1912, and where America’s first “Little Saigon” was built by the military. It may take a guidebook to tell all those stories that are transnational in surprising ways, crossing borders between Native and Spanish California, Mexican and Anglo California, Vietnam and Orange County too. A guidebook’s geographic orientation allows us to make such surprising connections across time in stories united by space.

Thuy Vo Dang: I would also add that the guidebook includes recommendations for nearby restaurants and sites of interest in addition to the description of places that tell us something about people or events missing in mainstream history. This also gives us an opportunity to explore and highlight businesses that are typically only on the radar of locals.

EL: the possibilities for guidebooks, traditional guides tend to encourage consumption Despite and spectacle, steering tourists and the tourist economy towards already-elite places. The current guidebooks to Orange County focus disproportionately on the half of Orange County south of the 5 freeway, guiding visitors to amusement parks, malls, and beaches, but not the “Immigrant crossing” sign … Existing guidebooks render invisible the diverse people who have labored here. They obscure the complex and contrapuntal story of this county.

RR: In light of the recent presidential election, does the guide’s effort to excavate the history of working-class, indigenous, and minority communities take on an increased importance? Why?

EL: In 1976, political scientist Karl Lamb declared, “As Orange goes,” so goes the nation, expecting then that Orange County would lead the nation rightward. Maybe it has, but, in the 2016 election, Hillary Clinton actually carried Orange County, not Trump.

Orange County has a well-deserved reputation for conservatism, from the prominence of the John Birch Society in the 1960s to the anti-gay Briggs Initiative of 1978 and the anti-immigrant Prop 187 campaign that originated here in the 1990s. Orange County’s mega churches have led some of its conservative activism, but other churches have also made this a center for international refugees. The nation’s largest military-industrial complex is here, fueling some of the county’s conservatism, but in an interesting dialectic it was also military personnel who desegregated much of this county. Harold Bauduit in Garden Grove, the Masuda family in Fountain Valley, and Dorothy Mulkey in Santa Ana were military veterans who pioneered desegregation. Our guidebook hopes to tell all those stories.

We may not be able to understand “as Orange goes” until we acknowledge all of our stories here, in their glorious contradictory variety.

Orange County was a leader of neoliberal privatization, with the nation’s first planned gated community, first age-segregated community, and first Home Owner Associations pioneered here after World War II, as well as the 1980s construction of California’s first privatized toll road. Yet it was also the site of the path-breaking school desegregation case Mendez v. Westminster (1946), the important housing desegregation case Reitman v. Mulkey (1967), and the surfers’ and environmentalists’ victory over a proposed toll road at Trestles beach.

We may not be able to understand “as Orange goes” until we acknowledge all of our stories here, in their glorious contradictory variety.

RR: The military’s complex history in Orange County on one hand spurs militarization and encouraged a conservative culture but also served in some instances as you’ve noted, as a force for integration. Can you expand on that historical tension?

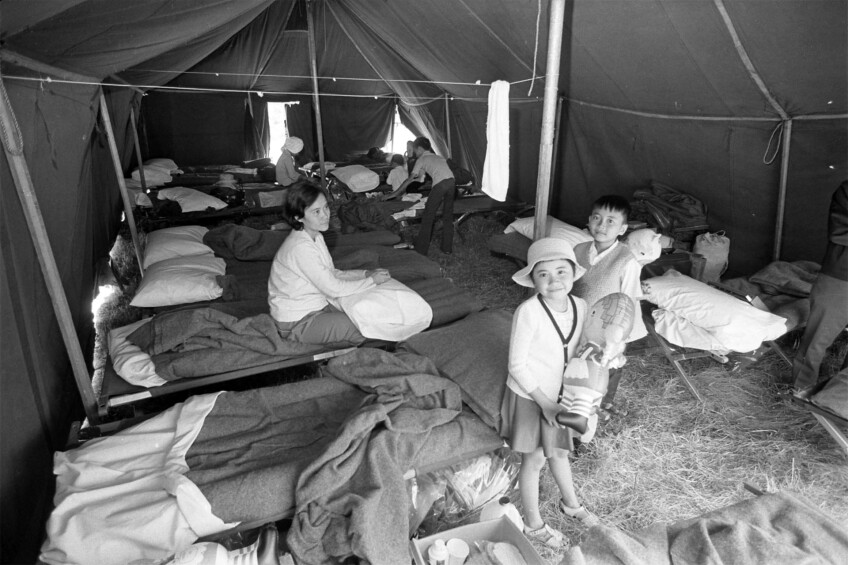

TVD: An example of how militarization is a mixed bag is the displacement of Southeast Asian refugees in the 1970s as a direct result of the U.S. wars in Southeast Asia. Immediately following the retreat of the U.S. from Vietnam, Camp Pendleton had to create makeshift housing to receive and resettle around 50,000 refugees. So our military had a hand in upending the lives of hundreds of thousands of Southeast Asians, effectively turning them into refugees – and then provided refugees care and support in the aftermath. Many resettled in Orange County, in large part because of the churches and faith-based organizations that offered social support. So as you can see, the strong forces of church and military in Orange County can help to explain why we have the largest population of Vietnamese outside of Vietnam right here in OC. Decades later we see the tangible ways Vietnamese Americans impact every aspect of the county, from its politics to its landscape.

RR: The People’s Guide series takes a multi-format approach, meaning that in addition to texts and photos there is an effort to use maps, charts, and other visual representation to get at the history and stories at the heart of each guide. How is the OC guide going about this and what advantages do you anticipate from this approach?

EL: We feel fortunate that Orange County has terrific archives for both photographs and oral histories. We are still collecting personal testimonies from activists. Our work with a mapmaker already made us see new sides we had not considered.

TVD: Using a variety of formats and media to share these stories of power struggles, resistance, resilience, and change is the way to provide the widest access possible to these stories – giving them back to the communities we are trying to represent here, and sharing them more widely to counter dominant narratives and perceptions of this county. It’s also an important strategy to meet communities where they are, using a range of tools to reimagine a county that is more inclusive. This history is messy, and perhaps using so many different formats might be perceived that way as well. I worked on a local history book (the first one on Vietnamese Americans) that used photographs and captions to tell forty years of the community’s history, and it became a vehicle to connect with people who are often never regarded as potential audiences for scholarly output. One of the highlights of my experience with publicizing that book was selling a few to a group of nail technicians in a Chicago suburb who ended up talking with me for hours about this history. They felt that the visual history was much more accessible. It’s so important to try different approaches and use photographs, maps, etc. with a project like this.

RR: What do you hope readers will take away from the guide?

TVD: I hope readers will pause to take a closer look at the places around this county that hold histories rendered invisible. I hope that readers will have conversations with us and with each other about how to dialogue with history in more critical ways, not accepting status-quo explanations for why things are the way they are.