How an Exclusive Club Helped 'Preserve' Nature While Pushing 'Progress'

This story is part of a series about the Automobile Club of Southern California's role in road development and the club's relationship with environmental and historic preservation. Read the first article in the series which recounts how the automobile club ushered car-friendly access to our National Parks.

At the turn of the 20th century, the prominent real estate developers Harry D. Lombard and Edward D. Silent were searching the greater region for an idyllic site to place a highly exclusive nature enthusiasts' club isolated from the increasingly busy pace of Los Angeles, a city just growing into its own at the time. In 1909, the two settled upon a 960-acre parcel of present-day Malibu Creek State Park, about 40 miles from downtown Los Angeles. After purchasing the site for $30,000 (just under a million dollars in today's currency), they named their retreat the Crags Country Club, a nod to the craggy landscape that they wished to maintain.

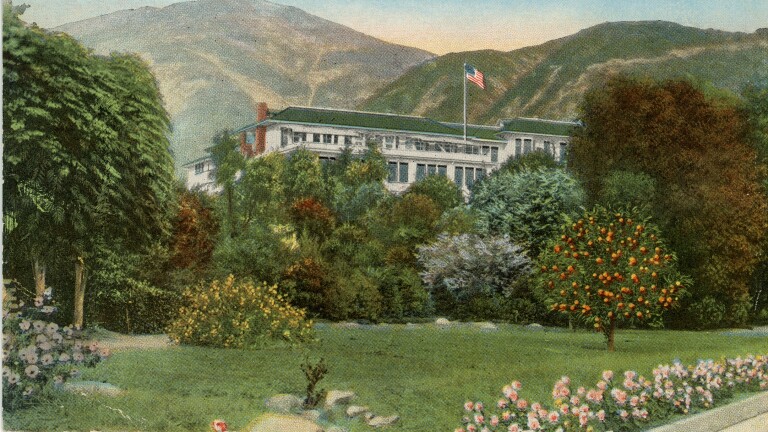

That same year, the Los Angeles-based Automobile Club of Southern California published its first issue of Touring Topics — a monthly magazine that would present images, stories and maps of the natural scenery throughout Southern California while, ironically, advocating for the construction of automobile roads throughout those very same bucolic landscapes. Three of the Crags Club's seven founding directors were prominent figures of the Auto Club: J.B. Lippincott, Sumner P. Hunt and Allan C. Balch. Though not as familiar a historical figure as his business partner William Mulholland, Joseph Barlow Lippincott oversaw the installment of a water tower that would serve as a reserve for Crags Lake, a man-made reservoir carved into the site for the purposes of fishing and general leisure. Sumner P. Hunt, one of the first practicing architects in Los Angeles, designed the Crags Clubhouse, a sizable structure of concrete, stone and heavy timber rendered in the Swiss-Chalet style in response to the rugged terrain that surrounded it. Allan C. Balch, who served as an Auto Club director from 1911 to 1939, had previously gained local prominence through his collaboration with William George Kerckhoff (himself a member of both Crags and the board of directors of the Auto Club) on the incorporation of both the Pacific Light and Power Company in 1902 and the San Joaquin Light and Power Company in 1905, and had likely helped set up an electrical system that powered Crags Clubhouse.

Beyond the seven directors, the Crags Country Club was limited to a highly exclusive membership of only 60 heads of families, several of whom were also Auto Club affiliates, including William George Kerckhoff, Joseph Francis Sartori and William Lucas Valentine. Together, the Crags members contributed to the development of the rugged site, defined primarily by Hunt’s lodge, Lippincott's water tower, a garage and a smattering of small-scale cottages. Its few members — each of whom had prominent standing in the city as owners of property and industry — were given privileged access to this secluded landscape, even as they had simultaneously catalyzed the rapid development of Los Angeles as the economic center of the western United States.

Despite its frequent use by those few members, the pathways leading to the Crags Country Club from Los Angeles were still a rough patchwork of varying road conditions. The overlap in members of Crags and the Auto Club led to the latter creating a remarkably detailed 'strip map' exclusively for the small number of Crags members living in the city. The map charted a round trip within the 41-mile span between the club and downtown Los Angeles. Given the physical limitations of the average car in this era, it was necessary for H.P.H., the map's principal cartographer, to painstakingly chart the contemporaneous material conditions of both routes of the round trip, thus ensuring Crags members could safely enjoy the scenic route around what was then an entirely agricultural San Fernando Valley. The longer drive to Crags via Van Nuys Boulevard, according to the strip map, was an entirely macadamized road before driving along a "good dirt road," while the drive from Crags back to the city was a particularly rugged drive, beginning with a dirt road before driving along the 'graveled' Ventura Road. Though the Van Nuys Boulevard route was nearly four times miles longer than the other, its lack of a speed limit, coupled with the relative durability of its macadamized road, likely made it a testing ground for the club members to race one another — a popular pastime for those who could afford it.

The round trip, however, was far more than a simple route. The map guided deep-pocketed Crags members through what was essentially an advertisement of a number of real estate investments held by members of both clubs,. The land occupying the majority of the round trip's interior, for instance, was a vast section of the San Fernando Valley recently sold by Crags member Isaac Van Nuys to the Los Angeles Suburban Homes Company, a recently-created syndicate led by Auto Club board of directors member Harry Chandler. Its land sales through that company began the year prior in what the Los Angeles Times (then-owned by Harrison Gray Otis, Chandler's father-in-law) called "the beginning of a new empire and a new era in the Southland." Between February and December 1911, the first true city of the San Fernando Valley was established, named 'Van Nuys' in honor of the land's previous owner. With similar intention, the route also passed through Owensmouth (now Canoga Park), a recently established town made viable by both the Janss Investment Company and the Owens River Aqueduct whose 100+ mile journey from Owens Valley would terminate within its borders in 1913.

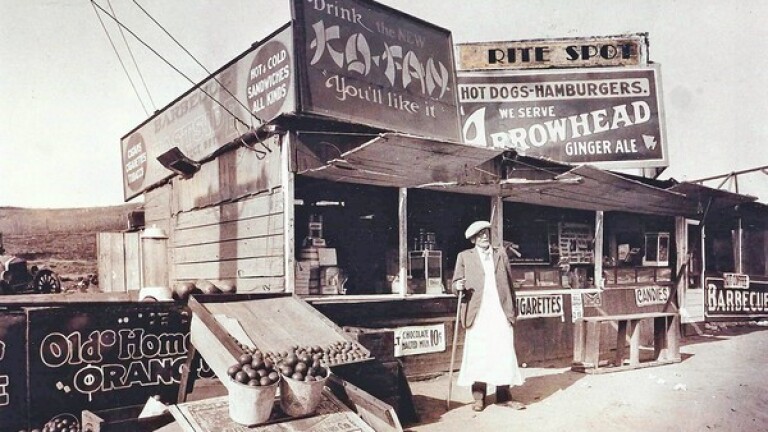

As the Auto Club members continued to make its mark on L.A.'s infrastructural ambitions in the following decades, its representatives could escape the hustle and bustle they brought about through a quick drive to the Crags Country Club. Touring Topics continued for several years to represent Southern California as both unspoiled and industrious without any apparent fear of contradiction (One article from 1915, for instance, described the Los Angeles area as "The Southern Europe of America, Where Century-Old Missions Resurrect California of the Spanish Regime and Hundreds of Miles of Boulevards Carry the Traveler Through Varied Scenery of Mountains and Sea-Shore, Orange Groves and Vineyards," before announcing the completion of a $4-million paved boulevard funded by L.A. County taxpayers).

After the club grounds had expanded to 2,356 acres in 1915, it would become more open to the needs of the burgeoning film industry as a site for those requiring vast natural settings — first with "Daddy Long Legs" in 1919, then later on with notables including "Tarzan Escapes" in 1936 and "How Green Was My Valley" in 1941. According to the historian Gary Liss, it was in these final decades that the club saw a decline in use following the Stock Market Crash of 1929 and the death of many of its founding members in the 1930s. Crags officially closed in 1946 when the property was sold to 20th Century Fox, the film distributor that had perhaps made the greatest use of the rugged landscape in prior years. Twenty-eight years later, the property was absorbed into Malibu Creek State Park when it was sold by Fox to the California Department of Parks and Recreation. Many of the original built elements of the Crags Country Club — including Crags Lake (now Century Lake, in a nod to its time as a film location for Fox) — remain to this day as reminders of the peculiar overlaps of conservation and development that were at the conceptual center of Los Angeles during its formation.

Additional Reading

Liss, Gary. "The Crags Country Club: The Origins of Malibu Creek State Park, A Community of Civic-Minded Leaders, and Visionary Conservation." Southern California Quarterly 100, no. 4 (2018): 409–70.

Duchemin, Michael. "Water, Power, and Tourism: Hoover Dam and the Making of the New West." California History 86, no. 4 (2009): 60–89.

Davis, Susan G. "Landscapes of Imagination: Tourism in Southern California." Pacific Historical Review 68, no. 2 (1999): 173–91.

Mauch, Christof. "Unruly Paradise—Nature and Culture in Malibu, California." RCC Perspectives, no. 3 (2015): 45–52.