Making Modern L.A.: When the City Was Lit by Gas

More than any other city the West, Los Angeles in the 19th century was dependent on new forms of energy to transition from a rural backwater to an up-to-date metropolis. Something as commonplace as street lighting took an enormous effort. Illuminating gas provided the first light in the 1880s. The city's oil fields delivered natural gas to light streets and homes in the following decades.

But making Los Angeles more modern made the city more dependent on burning a fossil fuel. The first era of gas gave Los Angeles light and heat, but at an environmental cost today's Angelenos may no longer be able or willing to pay.

To slow (if we can) the acceleration of climate change, the gas stoves and gas heaters that have been fixtures of Southern California homes may become as obsolete as the ornate gas lights that brightened Victorian Los Angeles.

There was a time, however, in the 1860s when gaslight was new.

More Light

Los Angeles came late to the gaslight era. Baltimore had gas street lights in 1817. New York's Broadway was fully lighted with manufactured gas by 1825. Gas street lights glowed in San Francisco in 1854.

Memoirist Harris Newmark remembered that in 1854 the streets of Los Angeles were entirely unlighted except for the "illumination from the few lanterns suspended in front of barrooms and stores. … In those nights of dark streets and still darker tragedies, people rarely went out unless equipped with candle-burning lanterns."

To lighten the gloom, the city council in 1860 granted two local entrepreneurs an exclusive franchise to establish a gas works and lay distribution lines. Like so many early attempts to modernize Los Angeles, the plan withered for a lack of capital and the high cost of raw materials. Illuminating gas was manufactured from coal, yielding a toxic, low-energy product called "coal gas." Coal was either a continent away in Pennsylvania or across the Pacific in Australia in 1860. Los Angeles did have asphalt — lots of it — except distilling asphalt yielded a poor-quality gas that was nauseatingly smelly.

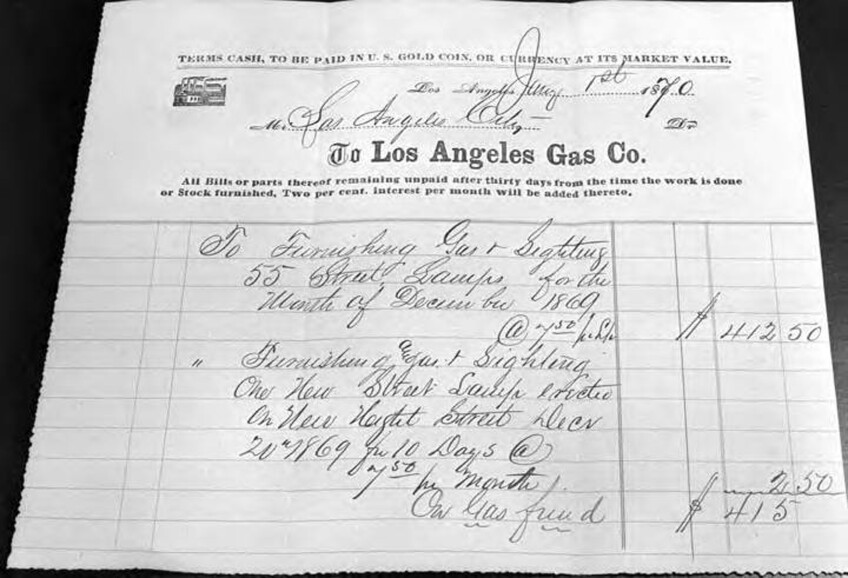

Finally in 1867, a newly franchised Los Angeles Gas Company began supplying gas to light city streets and some homes and businesses. By 1869, Los Angeles had 56 gas street lights, all within a few hundred yards of the gas works across from the Bella Union and Pico House hotels, both lighted throughout with gas. The rest of Los Angeles remained in the dark.

Modernity by gaslight was expensive. The gas company charged the city $415 in January 1870 for a month's supply gas, about $9,300 today. Individual consumers paid $7.50 per thousand cubic feet of gas in 1876 or about $165. (The same amount today costs $18.) Gas was a luxury. Ordinary Angelenos made do with kerosene lamps and tallow candles.

The gas company blamed the high price of gas on the cost of shipping coal from Australia. Angelenos blamed the gas company and agitated for lower rates, which were reduced to $6.75 per thousand cubic feet. The city council took the gas company's graft.

Exclusive franchises entangled Los Angeles politics and utility companies in ways that persisted for the next 50 years. The city council could demand service changes, set rates and revoke right-of-way privileges. The utilities countered by corrupting the city council. As historian Robert Fogelson noted, "Between 1865 and 1900 … the water, gas, and electric companies, the street railway lines, and the Southern Pacific Railroad were the most influential participants in Los Angeles politics."

More Natural

The first gas lights were hardly more than a brass tube, a tap to turn on the gas and an open flame that sputtered and flared from the tube's upturned end. By the 1890s, better gas fixtures produced a brighter and more even glow that extended work and leisure into the evening hours. But even in the filigreed Victorians of Bunker Hill and Angeleno Heights, rooms were only dimly lighted with gas, although its cost had fallen and its quality had improved.

By then, gas had a competitor. Electric arc lights, so powerful they had to be hoisted on 150-foot-tall masts to keep from blinding pedestrians, first rose over Los Angeles in 1882. Seven of these "moonlight towers" (because they cast about as much light as a full moon) illuminated the downtown business district. The first conventional street lights (called electroliers) lighted Broadway in 1905.

Competition from electric lighting drove the gas company to diversify, encouraging homeowners to replace wood and coal stoves with gas ranges and coal fired furnaces and water heaters with gas appliances. The gas company also went into the electrical generating and distribution business, fueling their steam boilers with gas distilled from oil.

Natural gas — a colorless, odorless gas drawn from oil fields — began replacing manufactured gas with the discovery of the Buena Vista oil field in Kern County in 1909. The gas company rapidly converted its system to cleaner burning natural gas and laid transmission pipelines from the oil fields to the old gas works on Center Street. Because gas use fluctuated with the weather and the time of day, the company began to store gas in large holding tanks; one was over 300 feet tall. These gas holders were the city's only skyline for decades.

Competition with electric utilities also led to consolidation. Pacific Lighting, a holding company, bought several small gas manufacturing and distribution companies, including the Los Angeles Gas Company, in 1890. These companies ultimately became the Southern California Gas Company, which remains the region's largest gas supplier.

The creation of a regional holding company also gave the utility greater political leverage. Cheaper natural gas, adept lobbying of the Los Angeles City Council and skillful public relations shielded the gas company when turn-of-the-century Socialists and Progressives campaigned for public ownership of water, gas and electrical utilities.

Era's End

The soft glow of gas lighting faded in Los Angeles during World War I. But natural gas in vast quantities was about to flow, along with hydropower from the Owens Valley Aqueduct and petroleum from the region's oil fields. Los Angeles finally had the energy needed to propel rapid industrialization, becoming by the end of World War II the most industrialized county in America.

Seven decades later, the second era of gas — from 1950 to today — may be coming to an end.

Sources

Fogelson, Robert. "The Fragmented Metropolis: Los Angeles, 1850-1930." Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1967.

Newmark, Harris. "Sixty Years in Southern California, 1853-1913." New York: Knickerbocker Press, 1916.