Paul Williams: A Pioneering African American Architect

In 1923, Paul Revere Williams was inducted to the American Institute of Architects as their first black member west of the Mississippi. This extraordinary feat encapsulated the efforts of an incredible young man able to overcome overwhelming odds and served as a launch pad into an illustrious future. Paul Williams was born to Chester and Lila Williams, a young couple recently relocated from Memphis, Tennessee with his older brother Chester Jr. At the age of two, Williams’ father passed away from tuberculosis, and two years later, his mother died of the same ailment. The two young boys were placed in separate foster homes but Paul was placed in the home of an encouraging family friend who “told him he was so bright he could do anything he wanted.” According to his granddaughter and biographer, Williams desired to design homes for families likely because he lost his own home and family as a child.

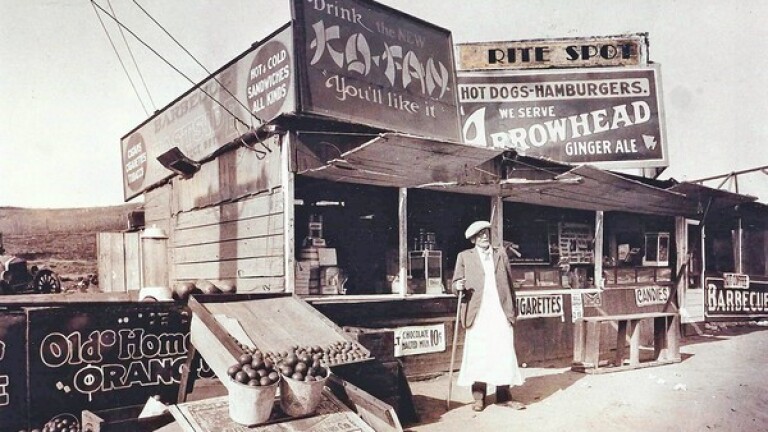

As one of the 3,100 African Americans in Los Angeles in the early 20th century, Williams claimed to have felt very little prejudice throughout his childhood. Not until he revealed to teachers at Polytechnic High School (historically located in downtown Los Angeles) that he desired to become an architect did he first experience discouragement due to his race. One particular teacher asserted that he would struggle to find white clients due to his race and that black Angelenos were not well-off enough to afford hiring an architect. Specifically he was warned, “Your own people can’t afford you, and white clients won’t hire you.” Still, Williams worked to become an architect. In a 1963 article for Ebony magazine, Williams penned a candid recollection of this exchange with his teacher and cited it as a turning point in his life. He asserted, “It prompted [me] to make an important decision: If I allow the fact that I am a Negro to checkmate my will to do now, I will inevitably form the habit of being defeated…And if prejudice is ever to be overcome it must be through the efforts of individual Negroes to rise above the average cultural level of their kind. Therefore, I owe it to myself and to my people to accept this challenge.” And with this sense of determination and a clear gift for sketching, he searched for internships at local architectural firms after graduating from high school. According to his biography, he went to each architectural firm in Los Angeles seeking work. Three firms offered him a position as an “errand boy” but the landscape architecture firm of Wilbur Cook Jr., responsible for landscaping the City of Beverly Hills, offered him an unpaid internship. Despite needing to be paid, Williams accepted the position and ultimately worked his way into a salary of $3 per week as an impressive young draftsman. In the evenings, he studied at the Los Angeles Beaux-Arts School, the local atelier of the famed Beaux-Arts School in New York City and ultimately graduated from USC’s School of Engineering.

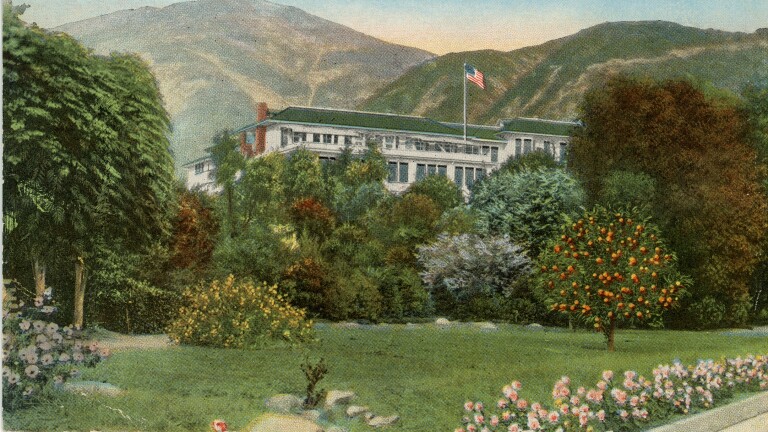

In 1920, Williams was appointed to the Los Angeles Planning Commission, and two years after becoming a certified architect, he opened his own firm using the $90,000 commission from the designing of the home of his high school classmate, Louis Cass, one of the original underwriters of the Automobile Club of Southern California. As an independent architect, Williams set out to make his mark across the city. Much of his work throughout the ‘20s and early ‘30s reflected the growing need of housing across the booming city of Los Angeles. Interestingly, it was during this time that he mastered the skill of sketching upside-down. While white clients were intrigued by his work, they were not comfortable with sitting shoulder to shoulder with a black architect so Williams taught himself to sketch across a table from white clients to avoid physical contact. In this manner, he designed nearly 3,000 private residences across Los Angeles alone.

By the 1940s, Williams’ work had become esteemed enough to attract the attention of major corporations and noted celebrities including Lucille Ball and Frank Sinatra. His commercial endeavors included the Music Corporation of America headquarters in Beverly Hills and the interior of Saks Fifth Avenue. Both spaces blended the comforts of a home with the professionalism of a working space. Each space also reflected the elegance of Williams’ many projects complete with low ceilings and smooth curves. By 1951, he completed the iconic Beverly Hills Hotel Polo Lounge, which continues to host the elite of Hollywood.

Click right or left to see inside Frank Sinatra's home, designed by Paul R. Williams:

To this day admirers of Paul Williams stand in awe of his contribution to the city of Los Angeles and its surrounding areas. Beyond designing homes for the wealthy of the city, he designed public housing projects like the Imperial Courts of South Los Angeles and a variety of churches including the First AME Church of Los Angeles originally founded by Biddy Mason in the late 19th century. One of his most cherished works was the Golden State Mutual Life Insurance Building, which housed one of the few black-owned insurance companies in an age where even buying insurance could be prohibitive to the black community. Paul Williams was passionate about demonstrating his architectural abilities within black communities. In many of his own writings, he asserted his ongoing awareness of how few black architects existed in the U.S. and how he viewed his work as a reflection of black capabilities. In tandem, he struggled over the reality that the majority of works he designed stood in communities off-limits to African Americans. By donating his time to civic projects, Williams believed his ultimate works would “further the health and welfare of young people and African Americans, and thus greater society as a whole.” This ideology is best demonstrated by the LAX Theme Building that greets the world when they arrive in the city.

Reflecting Los Angeles as a city of the future, the LAX Theme Building hovers over the airport granting each traveler both a welcome and a farewell. Williams’ lifelong efforts won him countless honorary degrees and awards in his beloved field of architecture and according to his granddaughter when they drove around the city and glanced upon cherished buildings of his design he always modestly summed up his career by stating, “That’s a fine piece of work!”

Click left and right to see the exterior and interior of the LAX Theme Building:

Author’s Note

The Louis Cass and Virginia Nourse Cass House in La Canada-Flintridge can be seen at the following web address: http://usmodernist.org/pwilliams.htm.

Top Image: Arrival area of the LAX Theme Building, which Paul R. Williams helped design | J. Paul Getty Trust. Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles