The Legacy of Multiracial Solidarity in L.A.'s Crenshaw Neighborhood

At a community center in a Los Angeles district with one of the highest concentrations of Asian Americans in the region, neighbors and community leaders gathered for two hours to discuss with the police what they perceived to be an alarming rise in crime and attacks. One after another, the victims — most notably, immigrant elders — stepped forward to give testimony about assaults on the street, robbery and house break-ins.

Not all the crime victims were Asian. At least one Black woman testified to being struck in the face with a pipe while some youths stole her leather coat. However, there was a clear pattern to the reports shared with the police that defined the tenor of the meeting. Asian elders expressed vulnerability in the face of attacks by African Americans and demanded greater protection from the police. The stories had aroused such public concern that two TV news channels were covering the tense community meeting.

A group of younger Asian American activists showed up in force to present a different perspective, one that directly challenged other leaders in their community. They shared the goal of ending the attacks on elders. But they did not see intensified police action as a solution. One argued that more policing would only harm Black youth, many of whom were already unfairly targeted by police abuse and racial profiling. Such action would inflame interethnic tensions, when community solidarity was most needed.

Uniting with African American allies, these Asian American progressives saw the problem and solution in structural terms. Polarized by race and class, the city lacked jobs and recreation outlets for urban Black youth, leading some to take their frustrations out on nearby scapegoats. Rather than alleviate inequity, schools had turned into "semi-prisons," responding to youth alienation through a framework of criminalization that only served to "escalate violence," according to David Monkawa.

The scene described above should be recognizable to anyone who has paid attention to the wave of attacks on Asian Americans that have occurred since the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as the #StopAsianHate movement that arose in response. The movement has created breakthrough moments of solidarity — both panethnic coalitions between Asians of diverse backgrounds and multiracial unity in the face of white nationalism. But media coverage has also created the perception, disputed by data, that Asian elders have been special targets of Black assailants. These incidents have fostered tensions between those calling for police protection and prosecution versus those advocating for restorative justice in line with "defund the police" and Black Lives Matter.

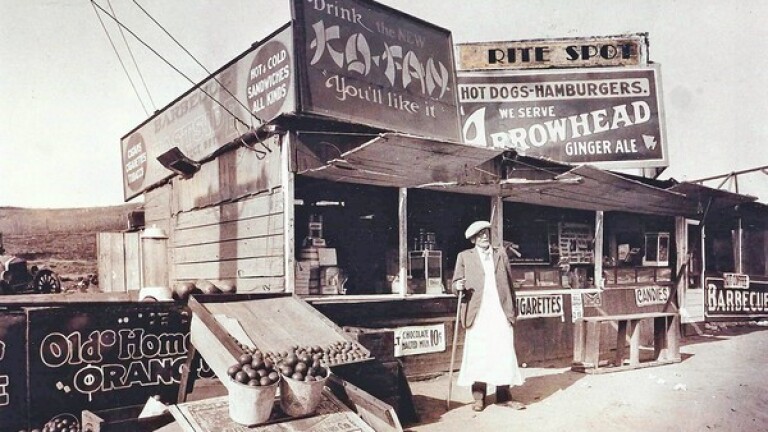

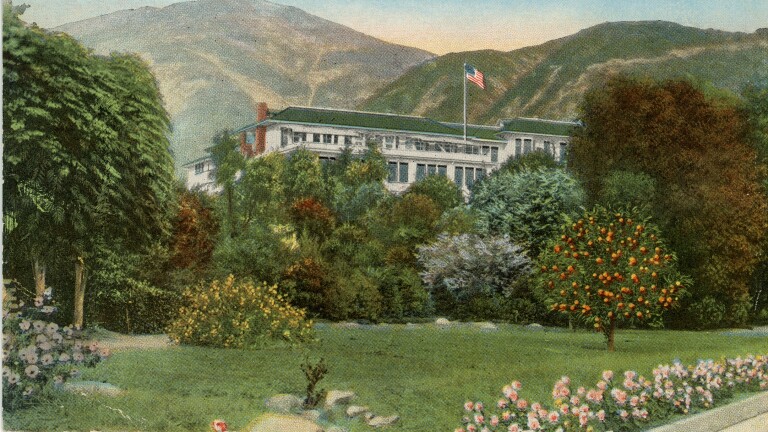

This meeting didn't happen in the past two pandemic years however, it happened nearly a half-century ago in 1973. It took place in the Crenshaw district, which had been a primary destination in the 1950s and 1960s for Japanese Americans, uprooted by wartime incarceration and looking to integrate new areas dispersed from the Little Tokyo ethnic enclave. The actions of the younger Asian American activists at the meeting also draw attention to the long history — largely unknown or forgotten within mainstream media and education — of Asian Americans challenging systemic forms of racism and injustice in ways that linked their fates to their African American neighbors.

Crenshaw was a hub for the Asian American movement in Los Angeles from the late 1960s through the 1970s. The reason we have a record of this meeting is that Monkawa, then a 22-year-old radical journalist and artist, covered it for Gidra — one of the many independent publications created by activists during this era. Like the Los Angeles Free Press, Gidra offered an alternative to the entrenched biases radicals saw in the corporate media. At the same time, as a publication started by students at the dawn of the Asian American movement in 1969, Gidra provided a break with a form of ethnic politics and identity the sixties generation found too steeped in assimilationism, moderation and the "model minority" stereotype. Monkawa was a regular staff member and contributor of graphics, articles and poems during Gidra's final two years of publication from 1973 to 1974.

Recently, I had the honor to invite Monkawa — still active in movement organizing today — to reflect on his upbringing in Crenshaw and involvement with Gidra. Although he came to the U.S. in 1958 for the first time at the age of 7, Monkawa was not an immigrant. He was born an American citizen, the son of a Nisei soldier who married a Japanese woman while stationed overseas.

During the 1950s, Leimert Park was arguably the most aspirational neighborhood for Nisei professionals and business owners, who built a small subdivision near the Holiday Bowl and Crenshaw Square. The Monkawas, however, lived literally and figuratively on the other side of the tracks, north of Exposition. David's father had been demoted by the U.S. Army for sharing blankets and supplies with poor Japanese civilians. He retired as a private, then struggled with health issues as a factory worker and gardener in Los Angeles. His mom worked as a babysitter during the day and cocktail waitress at night. The entire family of four lived in a one-bedroom apartment near Jefferson before the economic and social strain eventually caused the dissolution of his parents' marriage.

Monkawa attended Virginia Road Elementary School, which he recalled during our interview as being "90% Black and 10% Japanese." In this part of Crenshaw, you either learned how to fight or would "get destroyed if you didn't." In fact, most of his fights were with other Japanese Americans. His childhood best friend was Tony Richmond, a mixed-race Black-Japanese boy from a military family, who was raised by his Black grandmother. Monkawa said his political consciousness awakened as teenager in the 1960s watching police repression of Black Power groups, as well as harassment and brutality against African Americans he knew in the neighborhood.

The Black Panther Party had an office in West Adams, and three of their members "got slaughtered" by the police in front of a gas station in 1968. "That's only like a block and a half from where I lived at 29th and Norton [Avenue]," Monkawa recalled. Those killed — Steve Bartholomew, Tommy Lewis and Robert Lawrence — were just one to five years older than Monkawa, who was still in high school at the time. While he "didn't see the massacre," he witnessed the scene while the blood was still fresh and could see the Panthers "slumped inside" their car. Asking what happened, he was told, "Oh yeah, man, the cops rolled up on and just started shooting them."

Just as crucially, Monkawa began to rebel against the anti-Black prejudice he saw among the older generation of Japanese Americans, which tended to differ from overt hatred many whites expressed during the Civil Rights and Black Power eras. It was not usually spoken publicly or part of organized political pressure. Persecuted for looking like the enemy during the war, many Japanese Americans sought to distance themselves during the postwar era from the animosity whites aimed at African Americans. Such prejudice often surfaced through the use of derogatory anti-Black terms from the Japanese language. Some also harbored a "fear" of Black criminality based on racial stereotypes. Monkawa's parents, for example, used the address of a relative to move him and his sister to Audubon Junior High, where whites and relatively privileged Japanese Americans attended.

When Monkawa progressed to Dorsey High School, however, it fully reflected the changing makeup of the Crenshaw district. Some who attended in the 1950s recall the student body being an equal mix of Black, Asian and white. But white flight was already taking off and then accelerated after the Watts Rebellion. By the mid-to-late 1960s, Monkawa clearly sensed the school and surrounding area transitioning to majority Black.

To understand how Black-Asian solidarity developed in Crenshaw, one must appreciate that there was not a universal presumption of shared interests. Monkawa stresses that it often emerged from those willing to go against the grain. Malcolm X, the Black Panthers and many Black Power militants promoted an internationalist vision that particularly highlighted solidarity with Asian revolutionaries. While some Japanese Americans coming of age in this era fit the "model minority" profile of high-achieving students bound for universities and professions, many Sansei youth did not.

In response to Japanese and Asian American drug abuse, school dropouts and gang violence, the Yellow Brotherhood formed in the Westside in 1969. Much like the Black Panthers, its work combined study, protest, education and survival programs aimed to provide youth with self-pride, social consciousness and positive outlets for fitness and recreation. Though he was not a member, Monkawa was inspired by their work and recalls going to their house to "shoot pool" and "read Mao."

Monkawa defied the "model minority" in multiple ways while at Dorsey. He put his artistic talents to work making activist and anti-war statements on campus that made him a troublemaker in the eyes of the administration. In fact, Monkawa was effectively expelled and had his diploma withheld by the school. After Dorsey, he worked low-wage jobs, such as bussing tables in a restaurant, then attended Cal Arts on a scholarship until funding ran out before he could graduate. Ultimately, Monkawa made his way back to Crenshaw.

Although his close friend, Dean Toji, had become a member of the Gidra collective, Monkawa first dismissed this as "charity" work. But as the Vietnam War continued to prick his conscience and as he witnessed more and more Black and Japanese American friends in the community dying of drug overdoses, he resumed questioning power and oppression in society. As a result, Monkawa found himself drawn to the collective, eventually joining in its efforts. As a visual artist, he was particularly moved by a poster in the Gidra office linking corporate production of the "Napalm that blast Vietnamese civilians" and the "barbiturates that were killing African-American and young people and Japanese young people."

Gidra was not the only activist group working to make change at the time. Groups in the Crenshaw area were engaged in multi-faceted organizing. For a brief period in the early 1970s, a Marxist collective called Storefront sought to fuse community work, worker organizing and revolutionary education through its "storefront" office on Jefferson Boulevard. The organization emerged from a political study group of Japanese American activists who made a conscious decision to pursue "Third World" solidarity organizing, especially linking Black and Asian Americans. Meanwhile, some of Gidra's core members formed the Westside Collective, an anti-capitalist housing cooperative of radical Asian American activists, as well the anti-imperialist collective East Wind, which later merged with Chicano and African American-led groups to form the League for Revolutionary Struggle (LRS).

Gidra tried to remain above the sectarian feuds that often tore apart groups or caused internecine conflicts among leftists based on ideological differences. Still, it closed down in 1974, as did other radical initiatives of that era, following years of intensive, generally non-paid labor by young activists now reexamining their lives and work. Once driven by the belief that revolution was just around the corner, they adjusted to new political realities, family lives and careers. Monkawa continued with East Wind and the LRS, joining with Black, Latinx, white and other Asian American radicals to engage in organizing among labor unions, civil rights organizations, student activists and electoral politics.

Today, Monkawa remains involved in activism through the Progressive Asian Network for Action (PANA) and has returned to an apartment in Crenshaw. Amid new challenges and crises, many of his convictions remain remarkably consistent. In response to the rise of anti-Asian violence last year, he helped initiate the Neighborhood Safety Companions project in Koreatown, which works with local community members to promote mutual aid and support. As he advocated in Crenshaw five decades ago, Monkawa believes that true solutions to crime and violence must come from grassroots action for structural change based on multiracial solidarity and self-determination rather than escalated policing and criminalization.

I asked Monkawa if, at the ripe age of 70, he is still doing self-defense patrols on the streets with activists who are roughly the age he was when he worked on Gidra.

His answer? "Yes, plan to do it till the day I die."