Toyo Miyatake: Capturing the Stories of Japanese Americans in L.A.

It was several months into his forced incarceration at Manzanar when Toyo Miyatake shared an epiphany with his teen son Archie.

"As a photographer, I have a responsibility," Toyosaid on that dry October day in 1942 as he took out some lenses and film holders from a suitcase. “I have to take all the pictures in Manzanar to keep a record of what's going on here.”

None of it made sense to Archie at the time. “I didn’t know what he was talking about,” he recalled years later. But for Toyo, even without the benefit of years of hindsight and analysis, it was immediately clear to him that injustice had been served to his family and his people. He understood the power of photography, and showing what life was like behind the barbed wires at the concentration camps would ensure that this shameful episode in American history would never be repeated.

As the story goes, Toyo had smuggled in a lens and a film holder to Manzanar. With help from a carpenter and a mechanic, he built a camera around those parts with scrap wood and drain pipes. He was discreet at first, quietly taking photos of camp life and developing the films at night when everybody was asleep. This was a risky move for Toyo since what he was doing was illegal. “[He was] sure taking a lot of chances,” Archiesaid. But it was a risk Toyo felt he had to take since he knew in his heart that “this kind of thing should never happen again."

Toyo's wish from a lifetime ago still serves as the main inspiration and driving force for Alan Miyatake, son of Archie, who now runs the photo studio his grandfather started almost 100 years ago, and his father kept in operation until he took over. "I keep the studio going to serve the community and to keep his legacy of the Manzanar experience alive,” Alan said in a recent interview.

By the time Executive Order 9066 was issued on February 19, 1942, Toyo Miyatake had operated his eponymous photo studio in Little Tokyo for nearly 20 years. Originally located inside the Toyo Hotel (which coincidentally shared his name) in a block that would later be torn down to make way for LAPD’s Parker Center, the photo studio was purchased by Toyo in 1923 because “his mother convinced him to be a photographer so he would not be a starving artist,” according to Alan. Toyo had been interested in becoming an oil painter.

Toyo began his photography career with tremendous artistic aspirations. He had earned respect as a talented pictorialist within a crowded field of Japanese art photographers who were making their mark in Los Angeles. Modernist masterEdward Weston was a peer and mentor. Pioneering cinematographer James Wong Howe was a friend and collaborator. Popular actor Sessue Hayakawa, artist-poet Yumeji Takehisa and avant-garde dancer Michio Ito were subjects of his portraiture. At one point, Toyo was the official dance photographer for the Hollywood Bowl. Toyo’s artistic eye was a natural fit for the Hollywood and bohemian set.

With one foot firmly planted in pictorialism, Toyo let his other footloose and wander around his beloved Little Tokyo. He used his skills as a photographer to capture the day-to-day of Little Tokyo, which allowed him to get closer to the heart and spirit of the community and its people. “He used to walk around and tried to figure out what everybody did, what their habits were,” recalled Yoshiko Sakurai, a former employee at Toyo Miyatake Studio. "That's how where he learned to read human nature."

As the reputation for Toyo's skills in artistic portraiture grew, so too did business at his studio for the less glamorous but equally important work in wedding and family portraits. For the growing number of Japanese Americans in Los Angeles, Toyo became the go-to guy to mark the special occasions in their lives. He was so prolific at documenting the lives of Little Tokyo denizens that it’s not uncommon for people to walk into the Toyo Miyatake Studio and tell Alan that they had their photos taken by his grandfather. “That is really rewarding for me,” Alan said, “that they not only remember him and the studio, but they have trust in the studio that we will continue to do great work.”

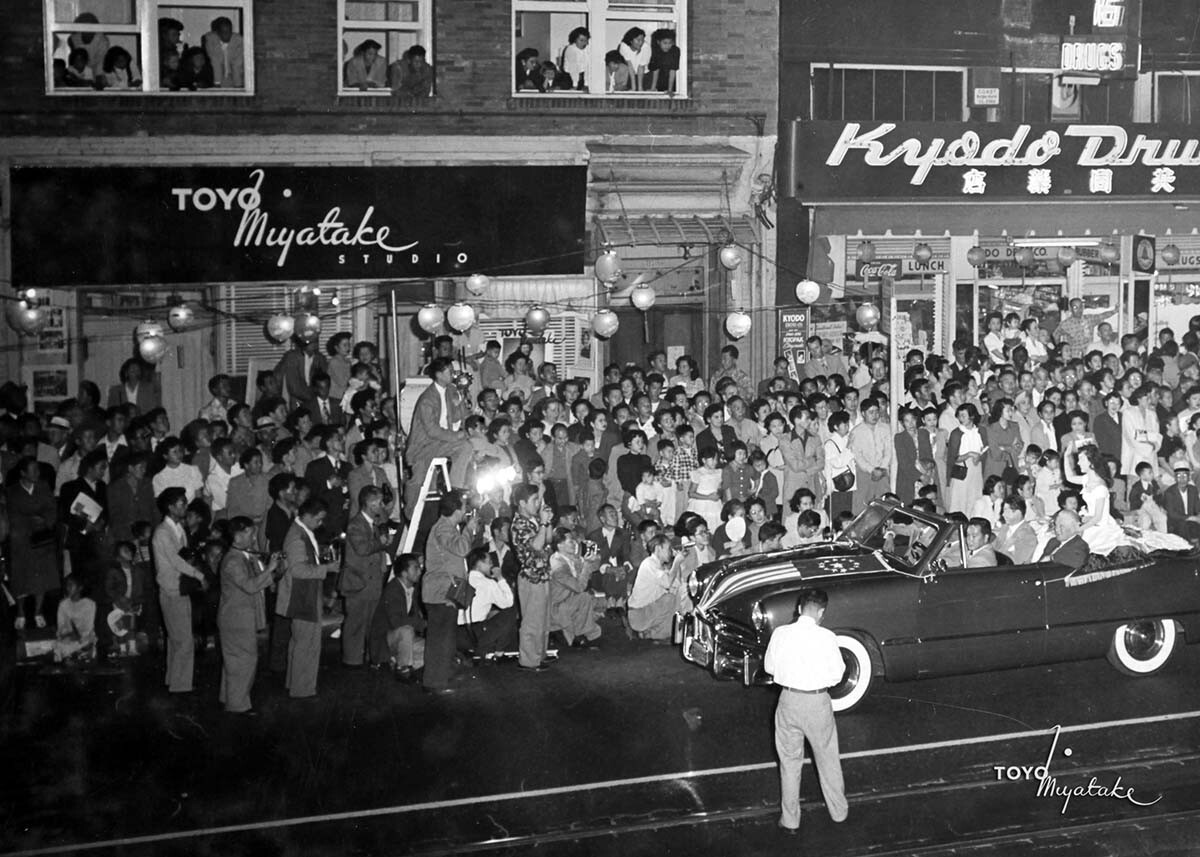

When Nisei Week Festival began in 1934 as a means to revitalize Little Tokyo businesses had languished during the Depression, the organizers knew exactly who to ask to take photos of the parade and the pageant Queens. After their return from Manzanar, Toyo and Archie helped revive the festivities after it had taken a hiatus during the war. Today, Alan serves as the third-generation Miyatake photographer to document the annual Nisei Week festivities. It’s a role that Alan has had since 1992, and hopes to continue for many more years to come. “Next year is the 80th Nisei Week festival,” he said. “I have been busy scanning my Nisei Week archives to be ready for their request to see and use old Nisei Week photos. It’s important to be ready for them.”

See how 1st street and the Japanese American community has changed over the decades through Nisei Week photos by Toyo Miyatake Studio. Click right or left below:

By 1944, Toyo had built himself a photo studio at Manzanar, thanks to a sympathetic camp director who turned a blind eye. There, Toyo would reclaim his role as community photographer, taking wedding and family portraits, school photos, unposed and candid shots. His years of experience before the war as the de facto community documenter of Little Tokyo had become indispensable as he took on a far more important task of bringing social justice to his people through photography. With the studio up and running, Archie began to assist his father and saw firsthand Toyo's dedication to serving the community through a lens. "He was doing it with a purpose in mind," Archie said.

Get a glimpse of the lives of Japanese Americans inside the camps through Toyo Miyatake's photos. Click right or left below:

When the Miyatakes were allowed to return home from Manzanar, they arrived back to Little Tokyo only to find their old neighborhood unrecognizable. It was now known as Bronzeville, with mainly African Americans living in the buildings formerly occupied by the Japanese Americans, and which the entire community had been forced to vacate. "Little Tokyo was not Little Tokyo anymore," Archie remembered. The house on East First Street, where he was born, had been torn down, replaced by a playground. "That was a big shock to me, because of the way it changed so much.”

In 1947, two years after returning from Manzanar, Toyo was able to re-established his studio. The location this time was at 318 East First Street, in the heart of Little Tokyo’s business district. Toyo went right back to work, and as far as business went, it was good. But from this point on, he never returned to his first love of art photography, whether by choice or not. He dedicated himself to serving the role as the documenter of Little Tokyo. He continued to document the Nisei Week festivities. He provided photos for the Rafu Shimpo community newspaper. When the Crown Prince of Japan came into town, Toyo was asked to take an official portrait. His photos became “a virtual archive of activities in Little Tokyo in the post-war years,” according to curator Karin Higa.

As Alan carries on the family business, he understands the important role his family has played in serving the community through photography. “It’s important to help Little Tokyo and Japanese Americans record their histories," he said. "As a business, you need to embrace your community. You need to service your community. Let the business run through the community so everybody can benefit."

Alan is confident that the Miyatake legacy will continue for many years to come — or at least for another generation. “My daughter has been working with me for a few years now, so there's hope we can make it to the fourth generation of Toyo Miyatake Studio," he said. Whatever the case may be in that regard, there will always be the invaluable archive of photos of the people, places, and irreplaceable history of the Little Tokyo Japanese American community, built upon by the three generations of Miyatakes. “We have many historic Japanese American events recorded and archived," Alan said. "With many of these organizations now celebrating their 100th anniversary, they call upon my services to record and celebrate these milestones. It's quite an honor."

Top Image: People crossing Manzanar camp | Courtesy of Toyo Miyatake Studio