Why Isn't There a Freeway to Beverly Hills?

It's the missing link of L.A.'s freeway network: the 2, a direct connection between the Westside's 405 and Hollywood's 101. Known to planners as the Beverly Hills Freeway, this 9.3-mile cross-town superhighway would have relieved pressure on the 10 and provided local freeway access to West Hollywood, Beverly Hills, and Century City. It also would have torn through some of L.A.'s wealthiest residential districts – a fact that ultimately relegated plans for the freeway to the trash bin.

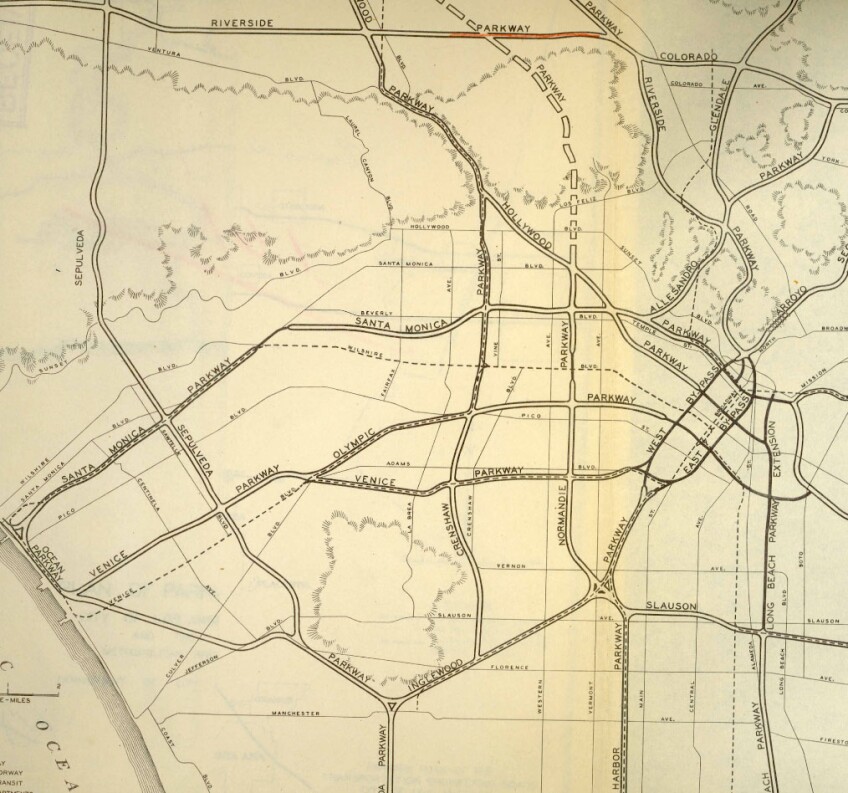

When traffic planners first envisioned the freeway in the early 1940s, they sketched it with a broad stroke on the city's map, labeling it the "Santa Monica Parkway" because it roughly followed the path of Santa Monica Boulevard. (Today's Santa Monica Freeway, completed in 1965, was born on the same map as the "Olympic Parkway.") By the time planners plotted the planned highway's precise course in 1965, it had earned a new name – the Beverly Hills Freeway – as well as the wrath of local communities.

On planners' maps, the Beverly Hills Freeway began as an extension of the Glendale (CA-2) Freeway at a massive interchange with the Hollywood (US-101) Freeway near Vermont Avenue. (The 101's wide median still anticipates that canceled interchange.) From there, the planned freeway sliced between Melrose Avenue and Clinton Street, before jogging slightly to the north and cutting between Waring and Willoughby avenues.

In West Hollywood, it turned to the southwest and followed the path of Santa Monica Boulevard, plunging below grade into a submerged trench. In Beverly Hills, the city considered capping the freeway with parking and surface street lanes. West of Beverly Hills, it emerged from its trench and passed by Century City before finally dead-ending south of Westwood at the San Diego (I-405) freeway.

Documents preserved and digitized by the Metro Transportation Library and Archive, including these two reports from 1964, recall the planned route in detail.

It was a bold plan that drew a correspondingly strong backlash. Though some constituencies – notably the businesses of Westwood Village, the developers of Century City, and much of Beverly Hills – supported the freeway, many neighborhoods opposed it. West Hollywood homeowners were particularly vocal in their dissent. The grassroots opposition might have seemed futile – Eastside neighborhoods like Boyle Heights, East L.A., and Lincoln Heights failed to stop seven freeways from bulldozing through their communities – but wealthy residents here did not want for political influence.

They also had time on their side. By the mid-1960s, the funding for freeways that once flowed so freely was beginning to dry up. And the Beverly Hills Freeway, which as a state rather than an interstate route couldn't access federal funds, carried a projected price tag of $300 million. A lack of funds -- as well as legislative battles in Sacramento and conflicts with the county and city of Los Angeles -- forced the state highways division to delay construction year-by-year, even as it purchased property along the proposed right-of-way. A turning point came in 1971, when the Beverly Hills city council reversed its longstanding support for the freeway. Still, Governor Ronald Reagan vetoed several bills that would have canceled the project. Finally, by 1975, ten years of inaction had ossified local opposition, and the state erased the Beverly Hills Freeway from official maps.