The Syuxtun Collective: Restoring Reciprocity with Health & Nature

What does it mean to participate?

In Robin Wall Kimmerer’s “Braiding Sweetgrass,” a beautiful, indispensable meditation on the gifts of reciprocity and participation with nature, she writes:

In the Western tradition there is a recognized hierarchy of beings, with, of course, the human being on top — the pinnacle of evolution, the darling of Creation — and the plants at the bottom. But in Native ways of knowing, human people are often referred to as ‘the younger brothers of Creation.’ We say that humans have the least experience with how to live and thus the most to learn — we must look to our teachers among the other species for guidance… They’ve been on the Earth far longer than we have been, and have had time to figure things out.

These words are no mere abstractions. They are an irresistible invitation to open up to a dynamic, reciprocal conversation with nature; to drop into learning from, and participating with, the silent wisdom of our plant ancestors.

A meaningful conversation relies heavily on the art of listening — to words, yes. But equally, and perhaps more so, to the spaces in between them, to the silence, to the information and unfolding wisdom that is available to us if we are able to connect to that silence. Instead, our unlistening minds are racing, eager to find the next clever or witty thing to say, to prove or disprove an opinion or agenda. We lose ourselves in the quest to be right, to dominate and control the conversation.

We stop participating.

This loss of authentic participation and reciprocity is evidenced not only in our relations with each other, but with our health, our bodies, and with the plants and animals with whom we share this planet. Many of us are coming to know and name this loss of authentic participation as the deep sense of isolation and helplessness that has become a hallmark of our culture. Despite relentless virtual “connectivity” through our screens and gadgets, we’re unable to ignore the gnawing pit of loneliness within.

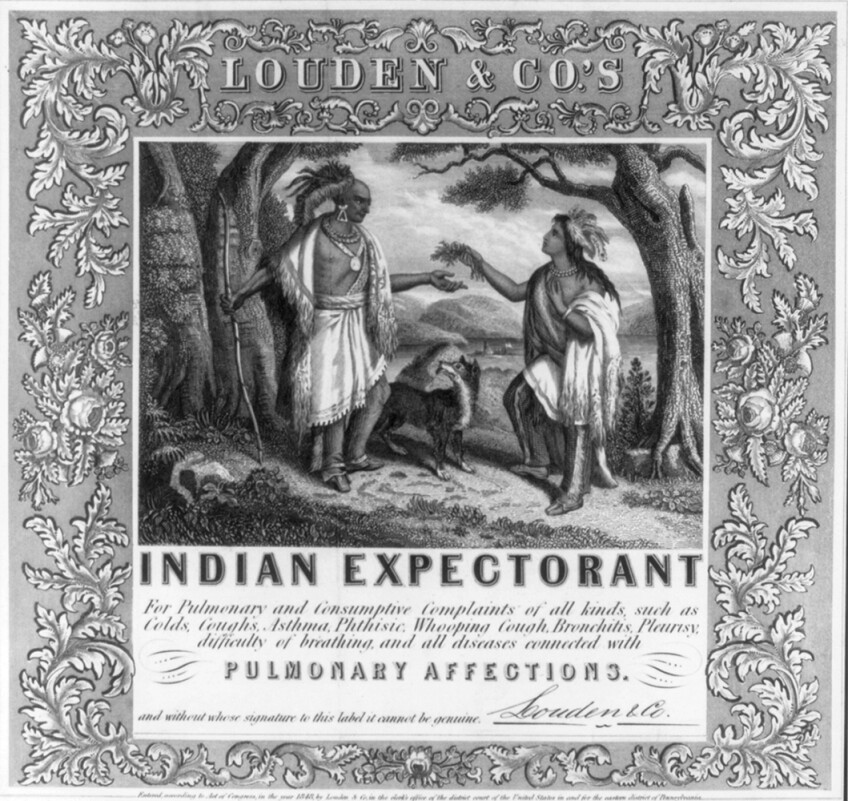

We have become testaments to a way of life that has deadened our senses not only to true participation with living nature, but with our own living bodies. The result is a proliferation of chronic disease, and a culture of dependence on aggressive pharmaceuticals that — like the unlistening mind — is interested only in silencing symptoms and controlling undesirable conditions, regardless of the costs, or side effects.

In contrast, Indigenous land stewards in California, for instance, still maintain a participatory relationship with nature, medicinal plants, and with health. The Syuxtun Plant Medicine Collective, made up of members of the Coastal Band of the Chumash Nation from Santa Barbara, and pioneered, among others, by ethnobotanist and herbalist Julie Cordero-Lamb, exemplify this subject-subject relational co-existence with our plant allies.

The Syuxtun Collective is named after the original village that Santa Barbara is based in. The word syuxtun, Cordero-Lamb tells me, literally means "it forks." That Cordero-Lamb picked this name for the Collective is significant: as humans, we are at a crucial fork in the road when it comes to realizing that the health of our individual, dynamic ecosystems is intimately connected to that of the Earth’s. This is no conceptual abstraction of the sentience of nature as something to be discussed and debated. As Cordero-Lamb so potently puts it, “There’s medicine that you can consume and there’s medicine that you can be.”

There’s medicine that you can consume and there’s medicine that you can be.Ethnobotanist and herbalist Julie Cordero-Lamb, founder of the Syuxtun Plant Medicine Collective

In allopathy, a disease or ailment is viewed in isolation. The person’s life history, lifestyle, diet and unique constitution are rarely considered; in other words, the dynamic, sentient ecosystem of the individual wherein an imbalance has taken place is generally ignored. And consequently, pharmaceutical drugs are administered, to first and foremost suppress the symptoms, and then to “manage” them. Addressing root causes, which would involve participating in making often challenging lifestyle changes, is more often than not, disregarded. We are given pills that bring some short-term relief — along with manifold long-term complications, not least addiction — and in so doing, we give away the power to participate in our own healing journeys. We neglect tending to the living soil of our health, injecting it instead with the equivalent of aggressive chemical fertilizers that deplete and destroy our inner biodiversity.

Similarly, pharmaceutical companies view the properties of medicinal plants in isolation. A chemical compound in a plant is identified, isolated and patented. The whole plant, the ecosystem that it is part of, the health of the soil in which it grows, and the humans and animals it has a dynamic relationship with is viewed as insignificant at best. What’s valued is the isolated compound, and the potential for patenting it, because: profit. It’s no news to anyone that Big Pharma’s agenda is not health, which after all, is not profitable. And yet, we continue to cede our power in participating and collaborating with our health, and doing the often difficult, but always rewarding, work of making changes to lifelong habits that do not serve us.

Of course, the allopathic model has valuable benefits and uses. Fixing a broken limb or undergoing necessary surgery is vitally important. The discovery of penicillin has been nothing short of a miraculous achievement of the modern age. Beyond that however, where prevention through nutrition and lifestyle, identifying root causes, listening and paying attention to one’s unique constitution and ecosystem and with the whole living system of a particular medicinal plant comes in, the conventional “scientific” model falls short. We have sacrificed true participation with our health in favor of quick fixes that bring with them their own litany of dangerous consequences.

In forgetting that symptoms are the smoke signals that our bodies send us as a way of communicating with us, of inviting us to participate in a dialogue towards health and balance, we have stopped listening. Instead, the prevailing western scientific paradigm has become one based on the transactional nature between subject and object. In this system, the “object” whether it’s our health, our bodies, or nature, is objectified to the point of lifelessness. Participation, and its companions, reciprocity and dialogue, are not possible with an object rendered lifeless. And this is the foundational bedrock of the allopathic model.

Through participating with nature, with our plant allies, and with our health, the Syuxtun Collective is responding to “the fork in the road.” Instead of ignoring this crucial choice point, and pretending that it will go away if we just carry on as “normal” by adhering to the Cartesian world-view of nature — within and without — as lifeless, and therefore something to control, dominate, exploit and commodify, the Syuxtun Collective embodies the power of living in subject-subject communion with the Earth and her gifts.

Indigenous traditions of tending the land, of living in dynamic, reciprocal relationship with our plant allies, of learning to listen to, and communicate with them, have all but been lost at the hands of colonialism and its legacies. Our health has also fallen victim to this loss. We have forgotten how to be medicine to the land, and to ourselves. Groups such as the Syuxtun Collective not only teach a remembering of this lost indigenous wisdom, of learning and listening, of harvesting and preparing plant medicine in participation with nature; they also strongly emphasize the importance of, in Cordero-Lamb’s words, “regenerative horticulture.” In essence, this is based on the indigenous science of exploring how embedded we can be in an ecosystem as a dynamic member of it. This seems to be the very definition of community, from the micro out to the macro; from the complex systems of atoms, cells and organs in our living bodies, all the way out to the networks of mycelium in the soil, to the communities of plants nourished by the soil.

“What’s really needed to combat climate change,” says Cordero-Lamb, “is a shift in world-view from the commodification of nature towards a more reciprocal, regenerative one.” When it comes to our own health, this can only have genuinely healing effects: we can begin to learn to work in collaboration with medicinal plants, learn how to nourish and care for them, and allow them to do the same for us. Most significantly, we can learn to participate in a system of healing that creates an empowering resilience instead of a disempowering dependence. This is a foundational tenet of all so-called indigenous healing modalities, including western herbalism, Ayurveda, Traditional Chinese Medicine and Native American plant medicine. It is not sustainable for human or environmental ecosystems to operate in a vacuum, where lifelong dependencies are peddled as beneficial to health and well-being. When the chemical compounds of a plant are isolated and patented, that plant becomes a lifeless commodity to be exploited forevermore. The human in turn becomes a mere consumer, with no active, reciprocal participation with the drug that she has become dependent on. Indeed, all of the healing traditions named above generally advise in favor of a “cycling on and off” period with the healing herbs and plant medicines they prescribe. This allows a person’s constitution to self-regulate, regenerate and build resilience, instead of dependence. And it prevents the plants from becoming relentlessly exploited and commodified.

We do not need to be of Chumash descent in order to learn to listen to and live in reciprocity with the Earth.

Groups such as the Syuxtun Collective are custodians and guardians of precious indigenous wisdom; wisdom that comes from the land itself, and that has been handed down generation after generation, barely surviving the onslaught of colonialism. But survive it has. And collectively, we are all at a fork in the road. We are experiencing first-hand the pathological ravages of colonialism and its dangerously reductive, binary-based world view in nature and in our bodies.

We do not need to be of Chumash descent in order to learn to listen to and live in reciprocity with the Earth. But we can look to organizations such as the Syuxtun Collective to guide us, and teach us so that we may also become custodians and guardians of valuable indigenous wisdom that this planet deeply needs us to learn and live at this time.