Arrested Development

The recent state Supreme Court decision to dissolve Community Redevelopment Agencies has left me with decidedly mixed feelings. Gov. Brown and others claim that CRA's commercial projects were largely unjustifiable politically and economically--giveaways to well-connected developers that the California public sector can hardly afford anymore. Most critically, opponents say that the CRA projects never seemed to really target the most blighted, development-needy areas -- i.e., inner cities -- that the agencies were meant to transform.

None of this is hard to believe. When I first started reporting in '92 for the L.A. Times in the wake of the civil unrest, the CRA was supposed to be a big player in rebuilding not just the burned-out sites, but the entire commercial infrastructure of South Central that had been steadily declining since the first historic unrest in Watts in 1965. Such expectations built up over so many years were probably too much to put on an agency that was only meant to bolster development efforts, not create them wholesale. But the reality was that in the riot-affected areas, significant development needed to be jump-started pretty much from the ground up. It's what was needed. The lack of development--commercial being only the most obvious kind--was a big part of the underlying problem of economic injustice that had fueled the unrest in the first place.

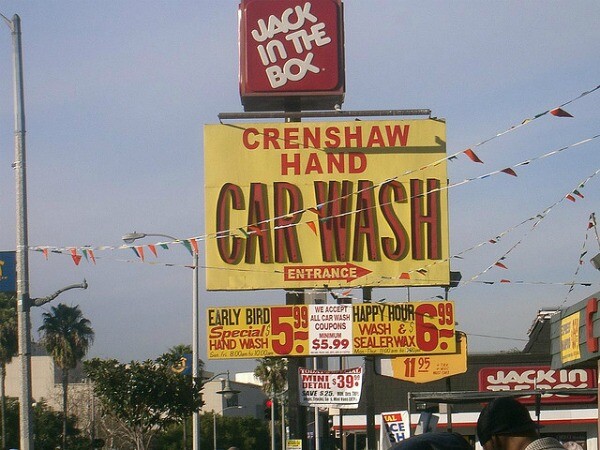

But politicians, to say nothing of developers, simply were not up to the task. The drama of April '92 attracted plenty of media attention, but ultimately not much money or sustained political will to remake a truly blighted landscape in a meaningful way. Yet the expectations persisted, not without reason. In the '90s I covered countless CRA community advisory meetings in the Crenshaw area, meetings in which residents--optimistically rechristened "stakeholders"--all weighed in on how they wanted a new and improved Crenshaw to look. The wish list included everything from more sit-down restaurants to better schools to more robust small businesses that also reflected the black heritage of the neighborhood.

Very little of what people wanted came to pass. It became to clear to me that the CRA could not in itself do anything; it was the handmaiden of city councilmembers who greenlighted development deals in their districts, or didn't. The deals (or lack thereof) had more to do with the particular vision of the councilmember than with anything else. If the councilmember was uncertain or unambitious, the CRA looked equally lackadaisical. Conversely, if the councilmembers were gung ho about fundamental and far-reaching transformation, as they have been in Hollywood and North Hollywood, the CRA looked absolutely heroic.

While South Central still sorely lacks heroism, and it's clear that the CRA alone couldn't make heroes, only enhance them, I wonder what will happen now that the biggest incentive developers had to come to the inner city at all is on the verge of disappearing . A good friend of mine who's an architect and veteran of the development wars in South Central and other places says the demise of the CRA bodes ill for South Central's future--a future that in the midst of the great recession looks much murkier than it did 20 years ago. "No, not nearly enough has been done in the 'hood, but you're taking away an important tool in the toolbox," he said, citing the CRA's role in attracting big-box retailers along Century Boulevard in Inglewood. "The elected officials don't know how to do deals, when they do them at all. But at the end of the day, the CRA is just better to have than not have." What he really meant is that once gone, nothing will take its place.

Journalist and op-ed columnist Erin Aubry Kaplan's first-person accounts of politics and identity in Los Angeles, with an eye towards the city's African American community, appear every Thursday on KCET's SoCal Focus blog. Read all her posts here.

Image via Flickr user Sean Loyless.